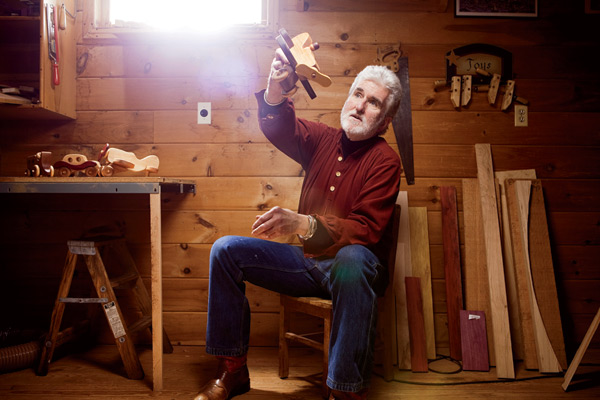

William John Woods, a maker of exquisite toys and rattles, knows about fine lines. He works with the grain of exotic woods and fashions his pieces by hand, with the eye of an artist. He knows that his toys must be pleasing to parents, but they won’t succeed unless they please kids. He also knows the fine line between making art and making a living. “You can’t spend all day making the one perfect piece,” he says. “You have to do 10 really good pieces. Otherwise you’ll be selling supersized fries.”

Seeing Woods at work in his shop in Ogunquit, Maine, doing what he loves and bringing joy to children, especially at this time of year, it would be easy to think that he’s one of the lucky ones who has found the line between too little and too much. But luck hasn’t had much to do with it. During a 35-year career making toys, he has had, at various times, to fill in by doing general carpentry, constructing cabinets, and building houses (“though that’s a young man’s sport,” he says).

Woods used to do 20 shows a year throughout the Northeast, but the road trips proved too inefficient and too expensive. He’s settled on just one show a year, the nine-day League of New Hampshire Craftsmen’s Fair at Mount Sunapee Resort in August.

He experimented with retail sales in specialty and gift shops but backed off because the demand was too high. To make a lot more toys, he’d have had to hire other people. “I’m a craftsman,” Woods says. “I’ve never desired to be a toy manufacturer.” Thanks in large part to the Internet, he’s grown and refined his business to a point where he can stay busy year-round, working comfortably alone, making toys that average families can afford.

On a cold morning in late November, Woods bends over a belt sander in his shop, making a really good rattle. He’s busy with Christmas orders. He’s glued thin blocks of contrasting hardwoods (purpleheart, yellowheart, and ebony) into the rough shape of a rattle, and embedded three or four brass BBs in cavities at each end; now, with 50-grit sandpaper whirring just millimeters from his fingers, he lets the belt smooth the hard, square edges of the wood into a sinuous miniature barbell.

His hands work quickly and surely, turning the rattle from end to end, spinning it off and back onto the belt, the wood disappearing from the blocks as if it were melting away. A multicolored whole emerges. “People don’t think of a sander as a sculpting tool,” he notes. “But that’s what it is.” He tosses the smoothed rattle into a plastic dishpan alongside others of different contrasting woods, and reaches for another set of glued blocks.

Woods works in batches, for production’s sake. The newest rattle will soon take its turn on a sander with a finer belt, then on a sander with soft inflatable spindles, then into a shallow vat of walnut oil, and finally on a mesh rack to dry–its color, grain, and finish growing more lustrous at each stage. Sometimes he pauses and just looks at the rattles shining on the rack. Every new creation, he says, still amazes him.

While the rattles dry–and before they undergo a round of 400-grit hand sanding, followed by polishing on the buffing wheel and a beeswax finish–Woods takes an inch-and-a-quarter-thick block of maple to his band saw and cuts out a body for a toy car. The fenders are bubinga, a gorgeous rose-colored wood favored by guitar makers. He scoops the trimmings into another plastic bucket. “These aren’t scraps,” he says. “They’re people bodies.” He’ll turn them on his lathe and, later, craft them into tiny two-tone figures that suggest drivers of cars and planes and helicopters.

Woods once made toy trucks modeled after the Hood dairy trucks he saw as a boy around Brighton, Massachusetts, where he grew up. Over time, though, he discovered the wisdom of making his toys more generic, to let kids imagine them however they wanted to. Each little figure could be a boy or a girl, a woman or a man.

The maple and bubinga, the walnut and cherry, shaped by the band saw, then sanded and finished, will become beautiful toys, no two exactly the same. To my eye, Woods’ pieces are better than “really good.” They’re works of art. “But they’re meant to be played with,” the toymaker says. “That’s the most important thing.”

To see more of William John Woods’ work, go to: ogunquitwoodentoy.com