Into the Wild | Maine Huts and Trails

A guided trip with Maine Huts and Trails allows a family of five to unplug.

The author's family quickly found the solace it was looking for along Maine's Dead River.

Photo Credit: Gina Vercesi

Photo Credit : Gina Vercesi

The woods behind my childhood house in Farmington, Connecticut, were an untamed space for countless imaginary dramas. My friends and I disappeared into the forest for hours, especially in the summer, returning at dinnertime, dirty, disheveled, and full of adventures. My children, like many today, don’t have access to free-range play in wide, wild territories. Instead, kids often turn to electronic devices, adventuring vicariously through handheld screens. I’m always on the lookout for antidotes to this plugged-in lifestyle, ways for my three daughters, now 14, 12, and 10, to have freedom to explore nature as I once did.

When a writer friend told me about Maine Huts and Trails, a nonprofit organization that operates a collection of four eco-lodges deep in the backwoods of northwestern Maine, I quickly got our family on the roster for a three-day guided paddling and hiking trip in early September.

The Maine Huts are the brainchild of Larry Warren, a Carrabassett Valley visionary who has long been known for doing big things in his small corner of Maine. Inspired by the Nordic hut-to-hut opportunities in the European Alps and the Appalachian Mountain Club’s hut hiking along New Hampshire’s Presidential Traverse, Warren imagined creating a multi-use system that would help protect thousands of acres of pristine wilderness. Now, 40 years after the idea first blossomed, and with the support of both personal and business sponsorships, the Maine Huts and Trails system launched its recreational corridor. It opened the Poplar Hut in 2008 and followed with three more over the next several years.

My family’s ultimate destination was the Grand Falls Hut, the most remote of a dozen huts the organization plans to build along a 180-mile stretch of trail from Moosehead Lake to the Mahoosuc Range.

Though our daughters are accustomed to their parents’ oddball penchant for off-grid exploits, they were skeptical of this particular venture. “We’re going to sleep in a hut?” they kept asking. In their minds we were leading them to one of the primitive lean-tos they’d seen on hiking trails.

Far more refined than the mental images inspired by the word hut, the well-appointed lodges are labeled as such because they can only be reached via human-powered means—by foot, bike, or skis. Each one offers guests comfortable, heated bunkrooms and hot showers; a hearty, home-cooked dinner upon arrival; and a bountiful breakfast. Evenings are topped off with an extensive local beer and wine list—a welcome treat for weary travelers.

Best of all, the Maine Huts and Trails website asks guests to leave their technology at home. Signs in the huts respectfully request that the space remains screen-free, encouraging analog entertainment—Scrabble, conversation, books with pages you actually turn.

We rose before dawn to reach the trailhead by noon, piling our sleepy, dubious daughters into the car with backpacks and sleeping bags for the seven hour drive to the Maine Huts and Trails headquarters in Kingfield, Maine.

Matt Rolfson, the guide who would be leading our trip, a six-mile paddle along the Dead River followed by a two-mile hike to Grand Falls Hut, had given me the GPS coordinates for the Big Eddy trailhead, deep in no-man’s-land. Wending our way along 15 miles of rugged dirt roads outside of Kingfield, we pulled into the trail’s parking area on the spot at noon. Only one other group joined us—a couple from Brunswick, Maine, Holly and Mitchell, and their two young daughters.

Pulling our packs from the trunk and hoisting them onto our backs, my 12-year-old glanced back at the car where we had just locked our phones and wrinkled her nose. “Say goodbye to civilization,” she said. I handed her the cooler bag that held our lunch and grinned.

As the September sun warmed our backs, we traipsed alongside Matt on the trail that led to the canoes. A student in the University of Maine at Farmington’s Outdoor Recreation Business Administration (ORBA) program, Matt is a dynamo outdoorsman with an easygoing, almost gentlemanly manner and a colorful backstory for someone so young. The 23-year-old Maine native has traveled the world with his parents, coached ski teams at Maine’s Sugarloaf, and survived a rainy summer leading youth groups through the Presidential Range. He is also a Registered Maine Guide, further testament to the hardiness of his character. We were in excellent hands.

The five girls ran ahead chattering like squirrels. At the put-in, they shed their shoes, wading into the river to collect current-smoothed stones for skipping. Canoes were taken down from racks and hauled to the tiny beach and we snapped ourselves into life jackets.

Following a brief lesson from Matt in the art of the all-important j-stroke, we were on our way. Five canoes slid into the water, each one holding a grown-up and a kid, and we moved downstream. The kids turned out to be more hindrance than help, focused as they were on the whirlpools they could make with their paddles in the silky black water. Sandwiches and clementines passed between the boats and we settled into an easy rhythm, breathing the crisp, pine-scented air.

The day was warm enough to inspire a quick swim, which required a scamper up the bank to don bathing suits behind some tall grass. Afterward, back on the river, Matt pointed to a bald eagle perched high in an evergreen and we speculated on our chances of seeing a moose—we never did, but the promise of spotting one stayed with us all weekend. After a few hours a small dock came into sight and we floated around a bend, ears filled with the rush of the Grand Falls cascade. With Matt’s guidance we hauled the canoes to shore, where they would remain until our return two days later. It was late in the afternoon at this point and we were on target to arrive at the hut in time for dinner at six. Wooden trail signs pointed our feet toward the last leg of the voyage.

The hut was a welcome sight as we emerged from the woods and dropped our heavy packs onto the wide, covered porch that circled the building’s perimeter. It had been a day of mild adventures, and the loud clang of the dinner bell sounded just as I was imagining what the homecoming would have been like had we traveled on skis or snowshoes for 14 miles in the depths of winter.

Meals at the huts are family-style events, with delicious, homey fare served at long wooden tables that glow in the early evening sunlight. Entering the hut’s impressive great room, our girls gazed up at the large windows and vaulted, wood-beamed ceiling. This definitely wasn’t the joint they’d been expecting.

Over big bowls of pumpkin pasta, our hut host, Sarah, shared the backstory and mission of Maine Huts and Trails, encouraging folks to become members—which we did—and inviting us to join her colleague Nate for a guided energy tour that evening—which we also did. Sustainability is at the core of each hut. Each building generates most of its electricity from solar and hydro energy methods; bunkrooms are heated using a radiant floor system that employs a wood-burning stove; and composting toilets require only three ounces of water per flush.

Later that evening, after sharing a bottle of Malbec with our traveling companions, Holly and Mitchell, by the fire, we nestled into our bunks, the only light coming from the glow cast by five tiny book lamps, and fell asleep blissfully disconnected from the outside world.

The next day was ours to spend as we saw fit and included hiking with Matt to Grand Falls, an impressive cascade 120 feet across and 40 feet high. The girls delighted in the discovery of a homemade fort in the woods and made pyramids of mud balls on the riverbank. Later, two of them insisted on going for a swim in the chilly water while two others returned to the hut to play games. My husband ventured off with our oldest daughter to fish and we arrived post-swim just in time to hear him whooping and hollering as he reeled in an impressive rainbow trout. For him, the trip was officially a success.

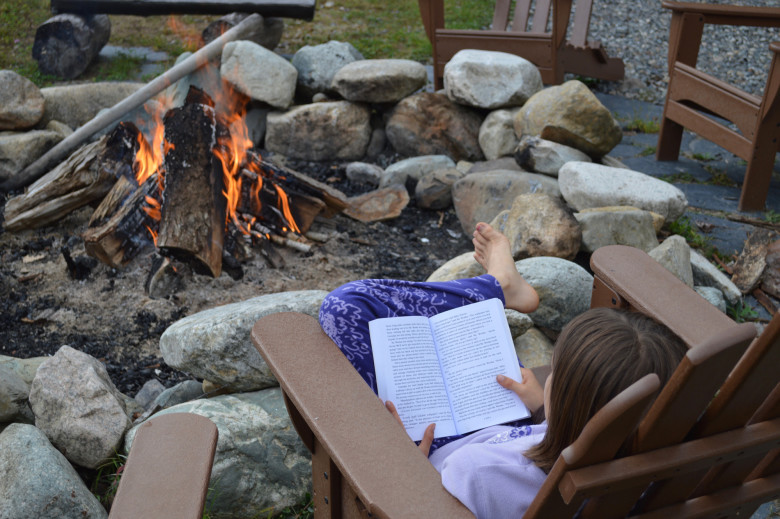

We whiled away the rest of the afternoon in Adirondack chairs around the campfire, chatting about ways we could move to the hut permanently, or at least apply to be hut hosts for a season. The kids built fairy houses out of bits of bark and moss, read their books, and played countless rounds of Tikki Toss on the porch.

Rain threatened on the morning of our departure and the skies opened biblically during the last mile of our hike back to the canoes. By the time we reached the dock, we were completely soaked and Matt swung into action, giving us instructions to get a dry layer next to our bodies. Misery ensued, but the sun soon emerged, warming our chilly bones and moods.

The paddle back felt longer than it had on the way there, as return trips often do in the absence of anticipation. We’d been dealt a harsh, albeit short-lived dose of wilderness and emerged from the woods with a sense of accomplishment and the feeling that we’d rekindled the lost art of being fully present.

My goal for the trip had been for our girls to lose themselves in the woods—to scale rocks and imagine mountains, to ford streams and envision raging rivers, to make believe deep in nature. Though our Maine adventure didn’t perfectly replicate the autonomous hours I spent outside as a kid, we nonetheless forged meaningful connections with both new friends and the natural world—just the balm we needed as we reentered our tech driven world.

Gina Vercesi is a New York-based freelance writer and nature girl with an adventurous spirit. Her work, which focuses on off-the-grid travel exploits, has appeared in numerous print and digital publications including the Boston Globe, Islands Magazine, and Lonely Planet. She also pens a travel blog called Kids Unplugged. She lives in a friendly village on the Hudson River with her husband, three daughters, and a very good dog.

“The way life should be”