Photographing Maine’s Blueberry Barrens

A cool mist and a milky, overcast sky mercifully keep the sun off the backs of the blueberry rakers on the desolate barrens north of Columbia Falls, in Maine’s coastal Washington County. Close to 100 rakers, stooped and sweaty, work their way across the vast open landscape, littered with pickup trucks and brightly colored plastic […]

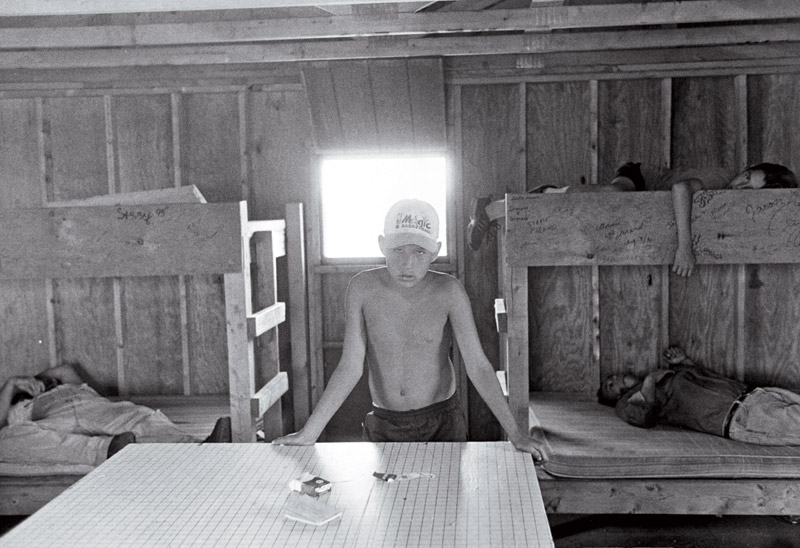

Cabin interior at Northeastern Blueberry Company’s Simon Camp.

Photo Credit : Stess, David BrooksA cool mist and a milky, overcast sky mercifully keep the sun off the backs of the blueberry rakers on the desolate barrens north of Columbia Falls, in Maine’s coastal Washington County. Close to 100 rakers, stooped and sweaty, work their way across the vast open landscape, littered with pickup trucks and brightly colored plastic tote boxes.

The majority of the rakers are Micmac Indians from Big Cove Reserve in New Brunswick, but the land itself is owned by Maine’s Passamaquoddy Tribe, which also owns the Northeastern Blueberry Company.

David Stess is one of the few Anglos on the Micmac crew. Bent at the waist, legs spread, his T-shirt and trousers stained with sweat, dew, and berries, Stess swings his two-handed aluminum blueberry rake into the low bushes, 60 long tines cleaning off the berries as he goes. When he has three or four pounds of berries in the rake’s scoop, he dumps them into a plastic tote. But it’s slow going this morning. Stess has arrived late, he’s nursing a bum right knee, and his row, marked off by long lines of twine, is overgrown with hay, requiring him to clean the rake every sweep or two.

A good raker, one who can steadily rake 100 boxes a day, is called a harvester. David Stess is a harvester. Fellow crewmembers call him “Super Dave.” He once raked 175 boxes, 25 to 26 pounds each, in a single day. But at 46, he’s slowing down. A 16-year-old Micmac boy raked 196 boxes just the day before, shattering the record. At $2.50 a box, that’s $490 for a day’s work.

Just after noon, the crew boss, a former chief of the Big Cove First Nations Band, arrives and drives slowly along the field’s dirt road in his big, black Dodge Ram turbo diesel, blowing the horn repeatedly. “Game over,” says Stess.

The Micmac crew traditionally works only a half day on Saturday. The rakers finish the strips they’re raking and begin hauling their boxes of berries, some dragging them with tethers, others lugging them in their arms, to the ends of the rows, where a tractor trailer will collect them and truck them away to be frozen. Stess has raked just 20 boxes this morning.

“Fifty dollars. That’s pathetic,” he quips. “I never leave the field without at least $100.”

As if having a bad knee, arriving late, and drawing a hayfield to rake aren’t enough, Stess has also been slowed because he stops every so often to take photographs. The morning’s work done, he puts away his rake and fetches a Mamiya 6, an ancient Leica, and a little plastic Ansco camera from his car. He takes a few pictures of three sturdy women, filthy but smiling, standing at the rear of their pickup. He may be Super Dave on the blueberry barrens, but back in New York City, where he lives most of the year, he’s David Brooks Stess, Photographer.

“It’s a great change from New York,” says Stess, who has been migrating to Maine for the blueberry harvest for 21 years now. “It totally detoxifies you.”

The rakers drive a mile or so down the road to the Simon Camp, a cluster of 20-odd wooden migrant cabins on the edge of the barrens, an abandoned Cold War-era radar installation marking the near horizon. Most raker families live in these primitive cabins. A few come with travel trailers. Stess lives out of the back of his station wagon and sleeps in a small tent next to the crew’s dwindling pile of firewood.

He’s looking forward to a hot shower, but as he fishes his toiletries and clean clothes out of his car, Micmac children gather round, eager to see his photographs. He has exhibited at the Center for Maine Contemporary Art, at the University of Maine campuses in Machias and Presque Isle, and at The Putney School in Vermont, but his primary audience is here on the barrens. Amidst the car’s clutter, Stess retrieves boxes of shots from previous seasons and hands them out free of charge to the rakers.

They’re all black-and-white, documentary-style photos shot on film and printed by hand. No quick-and-easy color digital images for Stess. He’s old-school. His work harks back to the Depression-era Works Progress Administration, when the government commissioned photographers to chronicle the lives of the rural poor.

The blueberry harvest Stess has been photographing since the 1980s is itself rapidly changing. In the field next to the one where he and the crew have been raking by hand, mechanical harvesters rumble across the barrens, raking in tons of blueberries and signaling the passing of a traditional way of life in Down East Maine.

Stess figures he needs at least one more year on the raking crew to complete his project. Then maybe he’ll start looking for a book publisher. At the moment, however, he’s still focused on raking enough blueberries to finance his photography. Fresh from the shower and flexing his sore right knee, Stess vows, “By the end of the season, I’ll be a lean, mean raking machine.”

VIDEO:David Brooks Stess photos of Maine’s Blueberry Barrens

Edgar Allen Beem

Take a look at art in New England with Edgar Allen Beem. He’s been art critic for the Portland Independent, art critic and feature writer for Maine Times, and now is a freelance writer for Yankee, Down East, Boston Globe Magazine, The Forecaster, and Photo District News. He’s the author of Maine Art Now (1990) and Maine: The Spirit of America (2000).

More by Edgar Allen Beem