The Lake Champlain Monster Believer | Yankee Classic

Joseph Zarzynski is convinced that “Champ,” the legendary Vermont Lake Champlain monster, is real. A Yankee Classic from June 1986.

“The Believer,” an ode to the mythical Vermont Lake Champlain monster, was originally published in Yankee Magazine in June, 1986.

Joseph Zarzynski is convinced that something “definitely larger than a fish” really lives in Lake Champlain.

A Gargoyle rises from the waters of Lake Champlain — a head with hornlike protuberances on the end of a long snakelike neck that merges smoothly into the huge, humped body of the beast, just visible beneath the roiled surface of the lake. Joseph Zarzynski has been waiting and planning and hoping for this moment for ten years, for the opportunity to prove the existence of the animal he calls Champ, Belua aquatica champlainiensis, a living fossil. Now it is right in front of him, and he doesn’t have his camera. He turns to run to the cabin for the camera. He cannot move. He is suspended — between the camera and the creature, between science and myth, evidence and faith. He wakes up.

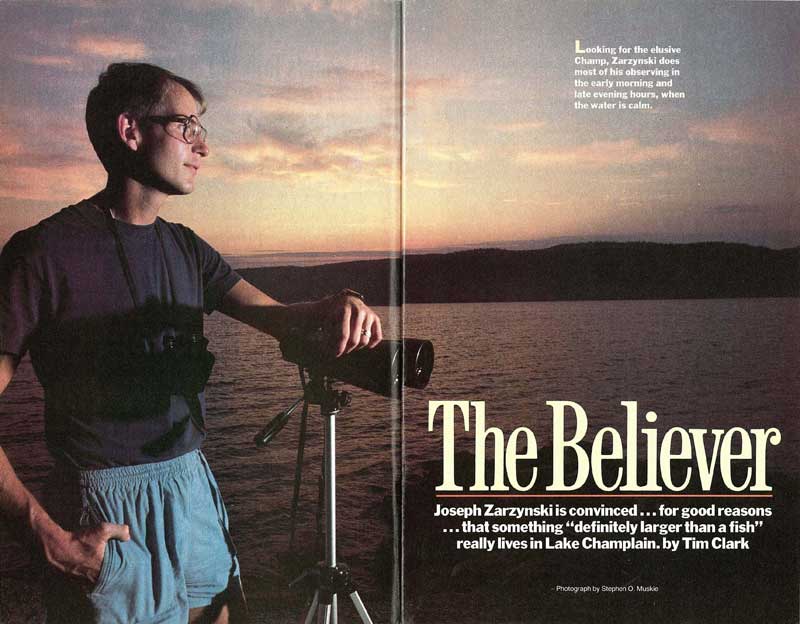

The lesson of the dream to Zarzynski, or Zarr as he signs his letters and is known to his friends, is never to be out of reach of a camera while in sight of Lake Champlain. He had one around his neck last summer when I drove up to the cabin in Vergennes, Vermont, that he and his wife of three months, Pat Meaney, rented. He kept it with him while we explored the rocky shore in front of the cabin and swam in the clean water of the lake, still cold in the last few days of July. He brought it with us in the car when we visited local people who claim to have seen the creature. It lay on the table on the front porch, overlooking the lake, while we ate our meals. We did not face each other while we ate. We watched the lake.

Zarr and Pat have grown comfortable with this man-woman-monster triangle. It may seem like odd behavior for newlyweds, but they are hardly strangers to one another. They met in 1974. Pat is the librarian at Saratoga Springs Junior High School, where Zarr teaches social studies. From time to time during the eight years they worked together before going out socially, Zarr asked Pat to look things up for him — historic sightings of strange beasts in Lake Champlain or Loch Ness in Scotland. “I figured he would never take an interest in me because he was so obsessed with Champ,” she recalls.

“Sometimes I become a little too obsessive about Champ,” Zarr admits, “but I think Pat understands that without this I’d be a . . . ” he pauses, searching for the word: ” . . . a crank.”

Zarzynski, 35 years old, a skeletal six-foot-five vegetarian and marathon runner (he has run the 28.5-mile road that goes the length of Loch Ness and is contemplating an attempt at the 109-mile length of Champlain), has become the leading authority on, investigator of, and recently, defender and spokesman for the large aquatic animals that may or may not live in Lake Champlain. He is the author of Champ: Beyond the Legend (Bannister Publications, 1984), founder of The Lake Champlain Phenomena Investigation, editor and publisher of Champ Channels, an irregular but entertaining newsletter detailing new sightings of Champ and such other lake monsters as Nessie in Scotland, Chessie in Chesapeake Bay, the skrimsl of Iceland, Shelly in Loch Sheldrake in New York, Ogopogo in Canada, and the mokele-mbembe in Africa.

In his book Zarzynski has cataloged more than 220 sightings of what he jokingly calls “USOs” (Unidentified Swimming Objects), dating back to a disputed reference to a 1609 encounter with the Lake Champlain monster by Samuel de Champlain, for whom the lake is named. While some of the sightings are clearly whimsical (“About 50 feet long, flowing red mane, dinner-plate eyes, mooselike antlers, elephant ears”), a large majority seem to be describing the same sort of animal: a snakelike body 25 to 30 feet long with two or three humps showing above the waterline, black or dark brown, green or gray in color. The witnesses include sea captains, ministers, doctors, passengers aboard the Ticonderoga, a high school principal, a state trooper, and Walter Hard, the Vermont editor and historian who wrote that he and his wife “saw something out there that was definitely larger than any fish. It didn’t fit the description of anything I’d seen or heard of before.”

Photo Credit : Aimee Tucker

Then there were Anthony and Sandra Mansi, a Connecticut couple vacationing with Sandra’s children in the St. Albans area in 1977. What they saw didn’t vary much from the standard description — a beast that was 15 to 20 feet long with a head and neck sticking six to eight feet out of the water and smooth dark skin. What was remarkable about the Mansi sighting was that Sandra Mansi took a photograph of what they saw, a photograph that first appeared in The New York Times in 1981 and was subsequently tested by scientists for authenticity. Their conclusions: The photo was of a real object in the water with no doctoring of the picture. Whether the object was a living thing or some kind of construction could not be determined.

Once interested in schemes to net a living Champ, Zarzynski now encourages legislation to prevent harassment of the creatures. In 1980 he persuaded the Village of Port Henry, New York, to declare its adjoining waters off-limits to anyone seeking to harm or destroy lake monsters; by 1982 the State of New York had passed similar legislation, as had the Vermont House of Representatives. Zarr was looking for a sponsor in the Vermont Senate when we met (he’s since found several). “I spend most of my time behind a typewriter or licking stamps,” he explained, as we made ourselves comfortable in rocking chairs on the porch, facing the lake. “Last year I spent only 17 days on the lake. This year, I’m spending a month.”

It was Loch Ness’s better-known mystery that got Zarr interested. After graduating from college and taking his teaching position in 1974, he started reading about the Loch Ness investigations. He visited Scotland in 1975, and enthralled by the history and romance of the legendary creature, became attentive to stories he was hearing about something big living in nearby Lake Champlain. He first visited the lake in 1975. By 1978 he was leading a week-long windjammer cruise in search of Champ. In 1979 he teamed up with engineer Jim Kennard, who was interested in underwater archaeology. Zarr swapped his historical research skills for Kennard’s expertise in diving and sonar. He became a certified SCUBA diver (Pat Meaney already was) and began accumulating bits and pieces of monster-detection gear: sonar fish-finders, movie cameras, an inflatable boat that he had to sell last year. But Zarr and Pat have never seen Champ or anything remotely resembling the creature. They’ve had some close calls.

During their stay at the cabin in 1983, they developed a hand-waving acquaintance with a fisherman who passed by every day in his boat. They went to a meeting in Burlington one night — the only night they didn’t spend on the porch — and the next day the fisherman stopped by to say he’d seen a disturbance in the water the previous evening and three great black humps rise from the surface.

Even worse was the near-miss a month before my arrival. Zarr and Pat had managed to squeeze in a week at the cabin at the end of June, but gale-force winds and driving rains ruined observations. On their last day — June 29th — Zarr packed up their gear and drove it back to Saratoga Springs, returning to Vermont that evening to give a speech at the Basin Harbor Club, a resort just south of the cabin. He found that his quarry had been seen there that afternoon.

“I was babysitting a dog and cat for Mr. and Mrs. Kerr while they were away for the afternoon,” said Peg McGeoch, a handsome lady in a black and white striped dress who was working at the gift shop at Basin Harbor when we caught up with her. “It was an overcast day. The lake was quiet, and there were no boats around.

“I was facing north in a chair by the window when I saw what I thought were three big fish doing a ballet. Then I realized it was only one. We watched for a while (she was with a friend, Jane Temple, who also works at Basin Harbor) when it was under water, then it surfaced again. The front end came out of the water about five feet, I guess. There were definitely two humps, and we could see space between the water and the bottom of the humps — it was snakelike.”

“Was the head sticking up at an angle, or was it arched?” Zarr asked her.

“It was like a caterpillar going along a table,” McGeoch said, demonstrating the motion with a finger. “And under the water, it was wiggling. Its disturbance was not a wake like a boat makes,” she added, forming a V with two fingers. “It was more like sideways ripples.

“He wasn’t looking around to see what he could see,” she said thoughtfully. “It was more purposeful, like, ‘I’m going down to Ticonderoga for something.’ Heading south.”

The two women watched the creature for seven to ten minutes. “A lot of that time was just watching the disturbance in the water,” she explained. “It was pretty exciting, I’ll tell you! It made a believer out of me.”

“What if you’d been alone when you saw it?” I asked.

“I wouldn’t have talked to you!” she said forcefully.

Photo Credit : Aimee Seavey

Later that evening we sought out another eyewitness, Ann Koch of Wilmington, Delaware. Her Lake Champlain monster sighting came on July 2 about noon, while she was opening her lakeside camp, several miles south of Basin Harbor, along with a friend from Wilmington, Rita Shaffer. “We had been cleaning and just sat down for a rest,” she said. “If we’d gone on cleaning for another ten minutes …. “

Ann had been to Loch Ness and was a believer in lake monsters in general, Champ in particular. Her friend Rita was a skeptic. But it was Rita who first spotted the undulating black hump and screamed for Ann to get a camera. Ann came outside just in time to see the creature submerging, leaving a broad, muddy wake in the shallow water just offshore.

“If I hadn’t seen it myself, I’d have believed Rita was making fun of me,” Ann mused. “And if I’d seen it, but Rita hadn’t, she certainly wouldn’t have believed me.”

We left and started looking for the house of still another recent witness. “We’ve had sightings by a women’s bowling team going into a restaurant, by a lady making a cake — one of my favorites was a young couple on their way to a football game who pulled over to neck,” said Zarro “We had a mass sighting off the Spirit of Ethan Allen last summer — more than 60 people saw it.”

Zarr tries to interview every witness and check to be sure what they saw was not one of the more prosaic inhabitants of the lake. “The first thing I look for is a head sighting,” he explained. “If there’s something sticking four or five feet out of the water, it’s not likely to be a loon. Size is important, too. If it’s 10 to 15 feet long, it’s probably not a sturgeon.” “Do you think there’s more than one Champ?” I asked.

He nodded. “And they have their own territories. You’d have to say that this area, from here up to Basin Harbor, has been a very active area, this year anyway.”

We were driving down a long straight dirt road without streetlights, looking for a yellow house belonging to a man who claimed to have taken videotape of the creature. In the bright moonlight every house looked yellow. We paused at every mailbox, straining to read the names. We couldn’t find it. Zarr was frustrated.

“A monster-hunter must be patient,” I reminded him.

“You try to learn something new every time out,” he said calmly.

Late that night I read the reports Zarr had been collecting of the summer’s sightings. One of the most interesting was a letter from a local writer named Pete Horton, who reported that on July 1 he had been sitting by Potash Bay (an inlet between the locations of the McGeoch and Koch sightings) reading, when he heard what he thought was a school of fish.

“But it was not fish making the noise,” Horton wrote. “First it looked like two merging boat waves. But there had been no boats. Then for a second it looked like two women with black bathing caps and black bathing suits. But there were no arms or legs. The noise was not a splashing. It was a steady rushing caused by three rounded black humps which were proceeding smoothly parallel to the shore … “

In the morning the fog lifted slowly, like a curtain, revealing the cliffs of New York State rosy in the level sunlight. Pat was in the kitchen, making blueberry pancakes for breakfast. “It’s a pleasure to cook for somebody,” she laughed. “All I do for Zarr is shred lettuce. “

Zarr was on watch. “In a place as beautiful as this,” he said dreamily, “Moby Dick could come cruising down the lake, and you’d be so absorbed in watching turkey vultures that you’d miss him.”

We ate, facing the lake. It was so quiet and still we could hear fish jumping, and the clicking of the sonar on the porch. “So many people talk about the commotion in the water, and the sound,” Pat said. “They look up because of the sound. When I imagine seeing Champ, I think about a big sound, a churning sound.”

“I imagine seeing what the Mansi photo shows,” Zarr declared. “I think it’s for real. She is a real person. She was trying to save her kids. She wanted to get them out of the water without alarming them, so she went down and said, ‘Come on, let’s go get pizza.'”

Those who like to speculate about the creatures — they call themselves “cryptozoologists,” meaning they study “hidden” animals – are divided about what they might be. One school of thought favors the zeuglodon, a primitive whale that was thought to have become extinct 20 million years ago. Others nominate the plesiosaur, a marine reptile with a snakelike neck and four large flippers to propel it through the water. It is believed to have died out between 60 and 70 million years ago. The coelacanth, a strange fish once thought to have become extinct at the same time as the plesiosaur, was rediscovered in 1937.

“I sort of expect it to be the plesiosaur,” Zarr said. “The Mansi photo looks like a plesiosaur. I imagine that when I see Champ, it will be a good sighting — eyeball to eyeball.”

“That would be good, wouldn’t it, Zarr?” Pat said. “In two feet of water?”

He chuckled. “Don’t hold your breath. The Vermont State Lottery ran a ‘Search for Champ’ contest, where you win if you find a picture of the monster under one of those scratch-off things. I never won.”

He spoke of one Loch Ness monster hunter whose tactics were to loudly announce his intention to go one place to observe, then go to a different spot to fool his prey. Another, a minister, believed in meditating to draw the creatures close. “I wish I was that positive,” he said wistfully.

“You’re the most positive person I know,” Pat retorted.

They fell into an old argument. Pat takes the pragmatic position that more publicity would help raise money for a more thorough search for Champ. She’d like to see the Mansi photo on postcards, for example. Zarr doesn’t want to appear to be exploiting the animal for personal or commercial gain.

“My hero in all this is Tim Dinsdale,” Zarr said, naming one of the Loch Ness investigators. “He claims that his search at Loch Ness is like looking for a unicorn in the water — a myth made real.

“There’s a purity there. We look at unicorn legends as a kind of last hope that there is some part of the human character that is pure. Here, we’ve associated these creatures with monsters, with the dark side of ourselves. If we can find one of these — Champ, Nessie, the Sasquatch — and see them as part of nature, not monsters, it might inspire us to achieve other things — find a cure for cancer.”

“We should send a copy of your book to President Reagan,” Pat said.

“We already did,” Zarr replied.

“It will be sad if they prove Nessie exists,” he went on, “but it will make a lot of people feel good.”

“Sad?”

“Yes, the mystery will be gone. This is the good part, the search. Any day could be The Day.”

“You sound almost as if you don’t want to find Champ.”

“Well, I wouldn’t throw away my camera,” he said. “But for a cryptozoologist, finding the animal means losing it. It’s not hidden anymore. Then it belongs to the zoologists.

“The mystery is gone for me already, in a way. I believe in the animal. But to someone like Ann Koch or Peg McGeoch, those sightings will become their little crusades for the rest of their lives, to try to persuade others.”

We watched the lake. A breeze came up, blowing away the last wisps of fog and cross-hatching the water with ripples. There seemed to be rivers on the surface, coiling up sluggishly from deep within, moving south.

“The Believer,” an ode to the mythical Vermont Lake Champlain monster, was originally published in Yankee Magazine in June, 1986.

Do you believe in the Lake Champlain monster?