Tracing a Winding Path from Cuba to Florida to Maine with Poet Richard Blanco

Tracing a winding path from Cubs to Florida to Maine, this Obama inaugural poet embraces the idea of finding home right where he is.

Richard Blanco

Photo Credit : Illustration by Xia GordonInterview by Melanie Brooks

Photo Credit : Illustration by Xia Gordon

Poet Richard Blanco lives less than a mile from the village common of Bethel, a picturesque ski town in western Maine, in a home set against a wooded hillside. Inside, its high windows flood the rooms with natural light, and outside, an expansive second-story balcony boasts a stunning view of the Presidential Range. Quiet and secluded, the space is any writer’s dream retreat.

“I’ve always craved that sense of home,” Blanco says, “and of all places, I found it here in Maine.”

For Blanco, a gay Cuban poet and civil engineer from Miami, discovering this feeling of community and belonging in Bethel—a town of about 2,600 people in the whitest state in the U.S.—was unexpected. But here he felt reverberations of his tight-knit childhood community of Cuban exiles who survived and helped each other as they navigated life in a new country. “Everybody here respects each other for who they are and understands that we all need each other. I like to say that Maine is like one big condo association,” Blanco says with a laugh. “This idea of one for all and all for one, because when eight feet of snow falls, you are in it together!”

A decade ago, when Blanco received the phone call from Barack Obama’s presidential inaugural committee that he’d been chosen as the inaugural poet, he was inspired in part by the kinship that he’d found in Bethel to write “One Today,” the stirring poem he read at the inauguration. And three weeks after the inauguration, on Blanco’s 45th birthday, the community gathered to celebrate his achievement. It was a touchstone moment in Blanco’s lifelong journey to understand his particular place in this world.

When Blanco’s mother was seven months pregnant with him, she left Cuba with Blanco’s father and older brother and flew to Spain. Shortly after Blanco was born, they immigrated to the U.S. and eventually moved to Miami, where he would live until he was 30. By the time he was 4 years old, Blanco had technically belonged to three countries. For most of his life, though, he struggled to connect with any of them. His quest to unpack his own history and to understand the broader questions of home, identity, and place is the beating heart of his work, which includes award-winning poetry collections such as City of a Hundred Fires and Looking for the Gulf Motel, as well as two memoirs.

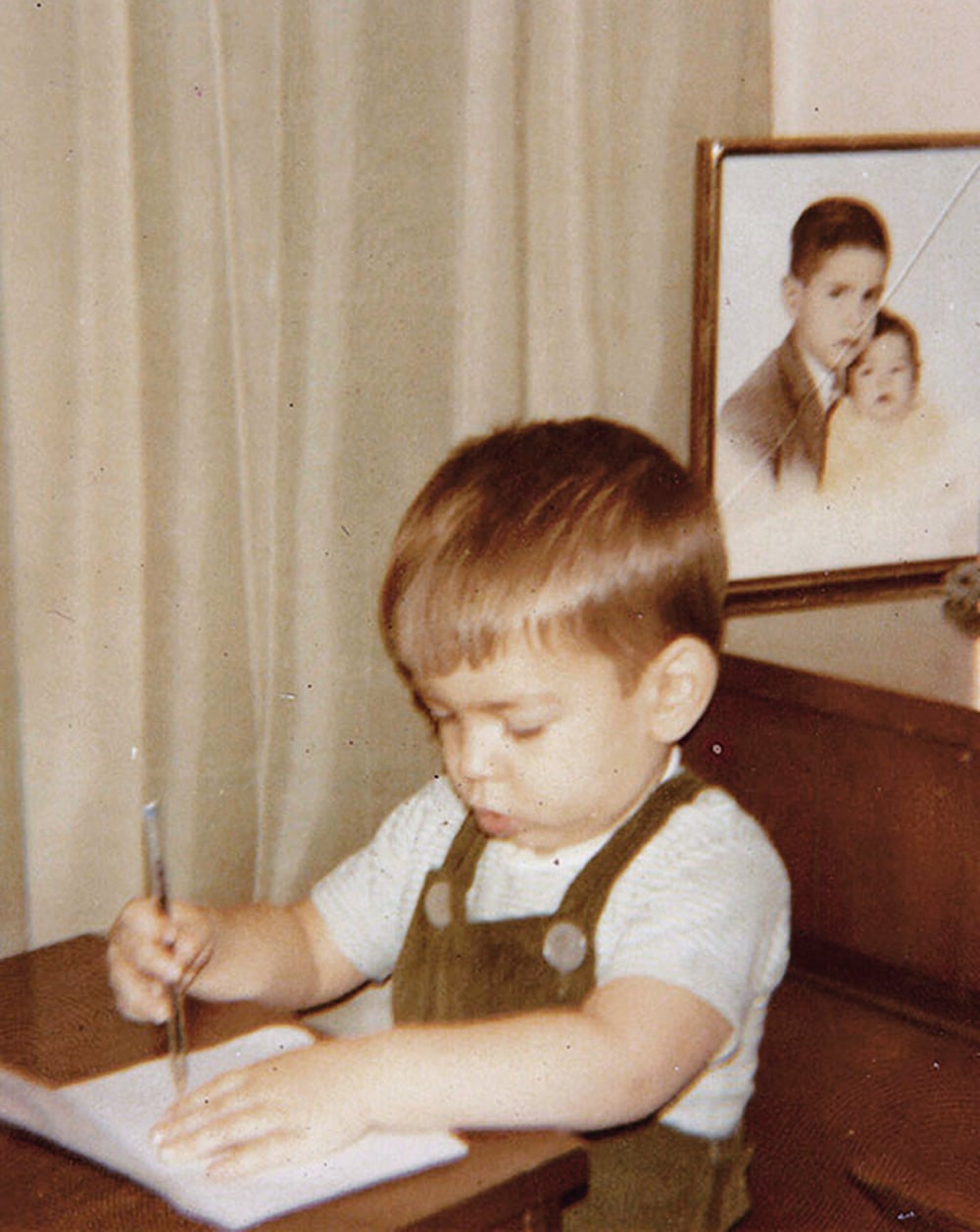

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Richard Blanco

Blanco’s latest book of poems, How to Love a Country, grapples with the questions What is home to all of us? and How do we embrace that home and each other as we confront the issues that are tearing us apart? His unflinching verse illuminates dark truths about America’s past and present, including racism, political strife, gun violence, xenophobia, and homophobia. Yet he shapes his words with love, clinging to the promises of what this country could be. “I’m not a writer of doom and gloom,” he insists. “I have to evoke hope because I want that hope.”

I met Blanco five years ago when I interviewed him for my book, Writing Hard Stories: Celebrated Memoirists Who Shaped Art from Trauma; that day, I felt the same approachability in person that I’d felt reading his work. When I proposed this interview, he invited me to stay overnight at his guesthouse. In June, I spoke with Blanco and his partner, Mark Neveu, over dinner in Bethel, and then continued speaking with Blanco about his life in Maine, his acclaimed work, and his plans for the future.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Melanie Brooks: Tell me about riding out the pandemic in Bethel. What was that year like for you?

Richard Blanco: As a writer I’m used to being alone, just at my desk, figuring out all of this stuff quietly. However, I really do miss the ritual of what poetry and being an author in the world had become, where you get to connect with audiences. Where they tell you stories across the book-signing table, or you get to see people’s smiles and tears and their reactions. And that, I really miss.

On a more personal level, this is my safe haven, in more ways than just the pandemic. My partner and I created our own little retreat in our house. Mark had never boiled an egg, and suddenly he became this gourmet chef! We’d have date night and have dinner out here on the deck. So the essence of why we came here in the first place—just to get away from it all—really helped to weather the storm, in a way. I was still in my house. Still writing every day. Watching the birds or the chipmunks.

I think we are all finally realizing a different kind of value to getting away from it all. And I think we’ve all realized that home is a lot larger than the boundaries of our front porch, and we’re understanding and appreciating what community really means. That whether you’re an engineer or an Amazon delivery person or a cashier at the grocery store or a teacher or a stay-at-home parent—everybody has the same value. And I think that’s such a beautiful and important lesson that I hope we take into the future.

M.B.: You speak to the idea of lessons we might learn from the pandemic in “Say This Isn’t the End,” the poem you wrote for The Atlantic in June 2020. Can you talk a little bit more about that?

R.B.:That was a really tough poem to write. I’ve never had to write about something that was happening while it’s happening, a moving target. I don’t write out of darkness. I’m a writer that writes out of hope, even when I’m writing from a social-political standpoint. I’m trying to find hope in all of this. It’s an insistence. So I tried imagining a post-pandemic world and thinking about a paradigm change in a way. What can we take with us? What can we hopefully not forget? So in that realm of things, just really honoring community. It takes a village not only to raise a child; it takes a village to sustain us throughout our entire lives. It’s about all those things that we took for granted and thinking about the larger scope of our vulnerability. There’s a line in the poem: “We’re never immune to nature.” We think that because we have all this technology or because we’re human beings, nothing can take us down. But there’s collective vulnerability here, and that feels powerful to understand.

M.B.: We definitely are all in a place of vulnerability now, and there’s this loud hum of anxiety all around us. I’ve heard you call poetry a “soothing balm” in times of trauma, and it seems like we need that balm now more than ever. How has that impacted your work?

R.B.: I think poets are always listening to that hum in some way or another. Not just in the context of the pandemic, but also in the context of all of the other reckonings that we’re having. We turn to poetry in moments of crisis because poets have been thinking about these things already, except maybe now it’s being heard a little bit more.

I recognize it’s an opportunity: Let’s record all this on an emotional level. Let’s deepen this because the fear and anxiety aren’t necessarily productive. So what do poets do? What do artists do? They take that anxiety and fear and distill it into something tangible, ground it in something that is larger than itself, and offer a way of weathering the storm. I think that’s part of what art always does. It documents what is a seemingly anxious or unfathomable moment, translating it in a way that we can digest slowly. Little by little.

M.B.: So what does that look like in your current writing?

R.B.: Because my space has been very closed off, instead of writing about the really grand things I’ve been writing about for the past eight years, I’m suddenly writing about chipmunks and asking, How do the small things speak for the whole? It’s a new challenge. I’m Cuban, and brevity is not the soul of our wit, but I’ve been finding myself attracted to the idea of economy, the brevity of what I have right in front of me. I cut my finger the other day, and I wrote a poem about that! I’m noticing the ant every morning—I think it’s the same ant—that wants to get into the agave syrup. Everything that was around me every day has suddenly become amplified because that’s all I have, and maybe that’s all I ever really did have. We still don’t know what’s coming tomorrow, so take it moment by moment. Slice it thin.

M.B.: When did poetry become your medium for making sense of things?

R.B.: I used to trace my discovery of poetry to when I started working as an engineer, believe it or not. So much of my job involved writing, all sorts of written and oral communication, which led to a fascination with language. That’s when I started writing creatively. I took a poetry class at a community college. I got into an MFA program. I got three books published. The White House called. Bada bing, bada boom. For most of my life, I thought that was the story of why and how I became a poet. But then, less than a year ago, I realized I never, ever remember not knowing two languages. Some of my earliest memories were of translating for my parents at 3 or 4 years old—not whole conversations, obviously, but small words or names of things. “How do you say this?” or “How do you say that?” I understood that my parents spoke and thought a certain way in their language and that I knew this other language as well and was capable of thinking of things in two different ways. So even though I was in my mid-20s when I began writing poetry, the seed of my fascination with language had been planted when I was just 3 years old. That’s really when I developed a love for it, an ear for it.

M.B.: How did your family react to your pursuit of poetry?

R.B.: I was already an engineer, so after that, it didn’t matter. My mother would write to family in Cuba and say, “He’s studying poetry.” She’d say, “Yeah, he’s a poet, buthe’s also an engineer.” She had to qualify that. I don’t blame her. Not just generationally, but also culturally. What could my being an American, English-language poet possibly mean to her?

M.B.: She doesn’t read English, right? So she can’t actually read your work?

R.B.: Right, but about three or four years ago, one of my books, Looking for the Gulf Motel, got translated into Spanish, and I sent it to her. Part of my motive, especially in my earlier poems, was to write about my parents, to write about their story as well as my generation’s story as the translators of those stories, as the “bridge generation” as we call ourselves. I feel like part of my writing has always been to heal my mother. She left her entire family behind in Cuba—eight brothers and sisters, parents, grandparents, everybody—for the sake of an American ideal that she didn’t even really understand. So she’s my lifeline to this country as well as to Cuba. And I’ll never forget the email she sent after she read the translated book. “I finally understand what you’re doing. I had no idea,” she wrote. “I never understood how much you loved us.” It was a breakthrough moment for my mother and me. She finally got me. She didn’t know how much I was paying attention. I think her sense of what I did as a poet really shifted. Even though she’ll still occasionally say things to me like, “Do they pay you for that?”

M.B.: When I read your work, I’m reminded of a quote by the poet Charles Simic: “I am in dialogue with certain decisive events in my life as much as I am with the ideas on the page… My effort to understand is a perpetual circling around a few obsessive images.” Your writing circles these obsessive images of your cultural heritage and identity, but also zooms in on the larger theme of home. When did that obsession begin for you?

R.B.: I think it started when I was in the womb. When I look back on my life, it’s a narrative that had been there from the very beginning, when my mother left Cuba. Then, growing up in Miami, which is such a cultural bubble because it doesn’t really feel like the United States, those questions of home and identity were always on my mind. Supposedly we came here to be American, but the quintessential America on TV was not like my home. The foods on TV and the foods on my dinner table were nothing alike. So since I was a little kid, I was always fantasizing about what it meant to be American. I always say I grew up between these two real, imagined worlds, living somewhere in between, waiting to finally get home—whether that was the old Cuba or the real United States. I didn’t realize I had all of those thoughts until my very first poetry assignment in my MFA program, which, ironically, was: Write a poem about America. And my mind just exploded.

M.B.: It seems like you’ve been trying to complete that assignment for your entire writing career. You repeatedly ask the questions: Where am I from? Where is home? Where do I belong? Do you feel like you’ve found any answers?

R.B.: For a while, I kind of gave up on the questions—or, should I say, I just started living in the questions instead of worrying about the answers. I’d moved to Maine because this opportunity arose through my partner’s work. And I didn’t really know what I was going to do here or write about. It was a leap of faith. But you know when you look back on your life and feel like it’s scripted somehow? Well, the White House calls and asks me to write a poem about America and all of those questions got tossed up in the air again. Writing the poem as well as the experience at the inauguration itself with my mother who grew up in a dirt floor home in rural Cuba. And there we were, sitting steps away from President Obama and Beyoncé. I realized, Wait! My questions about home are part of the American narrative. That makes me an American. Of course! The inauguration provided a kind of closure for my story and my mother’s story. We were finally Americans—always were, I came to realize. In a way, the poem is the response to those questions I had in my heart.

M.B.: After writing the inaugural poem, you seemed to lean into the idea that the poet has a civic duty to speak to issues that connect us all. How to Love a Country addresses important topics of this current moment head-on. Can you talk about that shift?

R.B.: Years and years ago, I created a spreadsheet with goals: personal, professional, spiritual—that was the engineer in me. And I wrote that I wanted to work toward being “a poet of the people.” If anybody is the poet of the people, it’s the inaugural poet, because the inauguration is arguably the most public event for poetry. Millions of people hear one poem all together at the same time. I felt a responsibility to the many communities of my country. And so I found myself drawn to writing poems that were “bigger” than me, yet still part of those very important questions of belonging.

How to Love a Country contains a litany of poems on everything from socioeconomics to gun violence—I became a more socially conscious poet. It was no longer just about me. But, like me, many of us have those same questions, that same yearning to find home right in our own country. It made me want to investigate those themes even further, and hold them up to the light of America’s promises of liberty and justice for all. It’s interesting that How to Love a Country feels like it was written yesterday, yet I started it back in 2014.

Using Country in a Sentence

From How to Love a Country: Poems by Richard Blanco

Copyright 2019 by Richard Blanco; reprinted with permission from Beacon Press, Boston, Massachusetts

My chair is country to my desk. The empty page

is country to my life-long question of country

turning like a grain of sand irritating my mind, still

hoping for some pearly answer. My question

is country to my imagination, reimagining country,

not as our stoic eagle, but as wind, the country

its feathers and bones must muster to soar, eye

its kill of mice. The wind’s country as the clouds

it chisels into hieroglyphs to write its voice across

blank skies. A mountain as country to the clouds

that crown and hail its peak, then drift, betray it

for some other majesty. No matter how tall

mountains may rise, they’re bound to the country

that raises them and grinds them back into

earth, a borderless country to its rooted armies

of trees standing as sentinel, their branches

country to every leaf, each one a tiny country

to every drop of rain it holds like a breath

for a moment, then must let go. Rain’s country,

the sea from which it’s exiled into the sky

as vapor. The sky an infinite, universal country,

its citizens the tumultuous stars turning

like a kaleidoscope above my rooftop and me

tonight. My glass as country to the wine I sip,

my lips country to my thoughts on the half moon

—a country of light against shadow, like ink

against paper, my hand as country to my fingers,

to my words asking if my home is the only

country I need to have, or if my country is the only

home I have to need. And I write: country—

end it with a question mark. Lay my pen to rest.

M.B.: What was it in 2014 that made you start writing about these issues?

R.B.: Artists are always pushing. We’re always looking at what’s not working. The circumstances that we need to keep on questioning. While it seemed on the surface that having an African American president was a huge milestone for America, and it obviously was, we—and I speak for all poets—we also knew that that was still part of our country’s narrative in progress. It wasn’t as if we checked a box, and racism was over. And of course a few months into Trump’s presidency, we had the events of Charlottesville.

M.B.: You speak to the despair that’s stirred up by things like Charlottesville, but I also hear a deep yearning in your poems for what this country can be. Where does that hopefulness come from?

R.B.: It’s quite a simple answer. That eternal hope comes from my parents, and especially from my mother. Immigrants, in a way, hold America up to its promises and they never give up. Their narrative is: I left my entire country; I left my family. This is going to work out. And I’m not going to give up on this idea. Certainly I will be critical, but I will not give up. And so it’s that spirit of hope that I carry, the quintessential “American Dream,” for lack of a better expression. My mother leaves Cuba for Spain seven months pregnant. Forty-five days after I was born, they move to the U.S. My dad starts working in a bomb factory. Their son grows up to become presidential inaugural poet. How can I not be hopeful?

M.B.: I know you’veconnected with Amanda Gorman, who read “The Hill We Climb” for President Biden’s inauguration. I’m curious what thoughts you’ve shared with her, in the process of passing the inaugural-poet baton.

R.B.: We connected before the inauguration. Her main questions to me were “What should I expect?” and “What is it going to be like?” There are only three of us alive, and, as my partner says, more people have been to the moon than have been presidential inaugural poet. It’s really beautiful, because in that moment every poet and their inaugural poem are like the snapshot of how America sees itself or what’s going on in America. And what I love about Amanda is that she represents this idea of keeping the youth of the country believing and dreaming and hoping that great things are possible. I feel that I sort of paved that road a little so that Amanda can keep on paving that road even further. Anyway, I told her not to worry; it’s going to be one of the most beautiful experiences you will ever have in your life. Just embrace it. Absorb it all.

Since then, we’ve been in touch now and then, following all the amazing things that are happening for her. I’m so happy that she’s getting that attention, not just for her, but for poetry. But I want to be the big brother whenever she may need to talk. I worry a little bit for her because she is so young, just 22. I nearly lost my mind because of all the attention, and I was 44! As for advice, I would say, “Just pace yourself. Remember, you’re going to be this person for the rest of your life.” You are never the “former” presidential inaugural poet. I’ll always be the fifth inaugural poet of the U.S. Amanda will always be the sixth inaugural poet. I try to discreetly check in with her every once in a while, to see how she’s doing emotionally. I’ll text her: Hey, how are you doing? Everything cool? I’m here if you need to talk.

Cooking with Mamá in Maine

From Looking for the Gulf Motelby Richard Blanco

(University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012)

Two years since trading mangos

for these maples, the white dunes

of the beach for the White Mountains

etched in my living room window,

I ask my mother to teach me how

to make my favorite Cuban dish.

She arrives from Miami in May

with a parka and plantains packed

in her suitcase, chorizos, vino seco,

but also onions, garlic, olive oil

as if we couldn’t pick these up

at Hannaford’s in Oxford County.

She brings with her all the spices

of my childhood: laurel, pimentón,

dashes of memories she sprinkles

into a black pot of black beans

starting to simmer when I wake up

and meet her busy in the kitchen.

With my pad and pencil eager

to take notes, I ask her how many

teaspoons of cumin, of oregano,

cups of oil, vinegar, she’s adding,

but I can’t get a straight answer:

I don’t know, she says, I just know.

Afraid to stay in the guest cottage,

by herself, but not of the blood

on her hands, she stabs holes

in the raw meat, stuffs in garlic:

Six or seven mas ó menos, maybe

seven cloves, she says, it all depends.

She dices about one bell pepper,

tells me how much my father loved

her cooking too, as she cries over

about two onions she chops, tosses

into a pan sizzling with olive oil

making sofrito to brown the roast.

She insists I just watch her hands

stirring, folding, whisking me back

to the kitchen I grew up in, dinner

for six of us on the table, six sharp

every day of her life for thirty years

until she had no one left to cook for.

I don’t ask how she survived her exilio:

ten years without her mother, twenty

as a widow. Did she grow to love snow

those years in New York before Miami,

and how will I survive winters here with

out her cooking? Will I ever learn?

But she answers every question when

she raises the spoon to my mouth saying,

Taste it, mi’jo, there’s no recipe, just taste.

M.B.:The attention that intensified for you after the Obama inauguration has opened so many doors to keep exploring ways to bring poetry to this country and also to New England. You’ve been commissioned to write poems for historic occasions including the Boston Marathon bombing, the reopening of the U.S. Embassy in Cuba, the Freedom to Marry movement, and the Parkland shooting. Now that life is beginning to return to some semblance of normalcy, what’s on the horizon?

R.B.: One thing that has been going on for a while is that I’m serving as education ambassador for the Academy of American Poets. My role is to serve in empowering teachers with approaches to teaching poetry so that they can turn their students on to poetry, make poetry more accessible to them. “Village Voice” on WGBH Boston Public Radio has been a wonderful project for maybe three or four years now that gives me the chance to feature poems and poets that help us to make sense of current events.

Photo Credit : Alissa Hessler

M.B.: Are you working on other new projects?

R.B.: I don’t know what it’s going to be quite yet, but I’m working on the next collection. I’m thinking about place or belonging in a more detached way. The idea of just being. I feel like I’ve become, but what does it mean to just be? I’m thinking about home in different ways: my poetry itself, my body, nature, chipmunks… I’m just waiting for the next iteration of home.

Also, my memoir about growing up in Miami got optioned, and it’s under development for a TV series with Michael Eisner’s company, Tornante. It’s a dream come true because I’m a TV-holic—I call myself a TV-ologist. I have always appreciated television in the ways that it unites us through storytelling. TV has played a big role in how I conceptualized America. I hope that the TV show will broaden the narrative of what it means to be an American today.

But the thing that’s really bringing me back into Bethel—and maybe back to where we began this conversation—is a play I’m writing, commissioned by Anita Stewart, the artistic director for Portland Stage in Portland, Maine. I collaborated with Vanessa Garcia, a very talented journalist and playwright from Miami. We just finished the first draft about two or three weeks ago. Tentatively it’s called Sweet Goats and Blueberry Señoritas.

M.B.:That’s a title! What’s it about?

R.B.: Of course it’s about food. But it was really inspired by my yearning to explore the intersections of different people and cultures in Maine, and represent that in a new light, think about who we are and what we’re going through now. And to challenge some of those stereotypes that people, including me, have about small towns in New England.

When I first moved here, I was looking for Pilgrims and sleigh rides. I thought it was just going to be this white, monolithic world. I’d tell people, “I’m from Cuba and I’m gay,” and they’d just look at me and respond, “So what?” Nobody was making a fuss. The people in Bethel were actually more surprised to find out that I am a poet and an engineer. I had never eaten Korean food until I came to Bethel. We have a Korean restaurant here, of all places! What I discovered is that people with all sorts of personalities and different backgrounds can come together and get along.

So the play is an ensemble piece of multidimensional characters including two guys who come up here to become country gays—based, obviously, on Mark and me, but also very different than us. Another character is a Cuban woman who ends up in this small town because she marries a Mainer who she meets in Miami.

We’re staging the play with frames—a nod to the pandemic and to Zoom. Vanessa and I started thinking about ways in which we’re framed not only through devices, but more so through the figurative frames of cultural norms and stereotypes of ourselves and others. So everybody speaks through frames to each other. But the frames slowly start falling apart and at the end there is no frame around anyone. They are all in the same space. It’s kind of a happy ending of how people come to understand each other.

M.B.:It sounds like a story that speaks directly to your overall artistic vision and hope.

R.B.: Indeed. As a poet, it’s my job to see. To see beyond just the expected, the surface of things. To see what we really could be. E pluribus unum. Out of many, one.