Magazine

The Education of Laura Bridgman | Yankee Classic

When this courageous New Hampshire girl learned to communicate, she broke ground for Hellen Keller.

The following is an abridged version of “The Education of Laura Bridgman” by P. Bradley Nutting, October 1987.

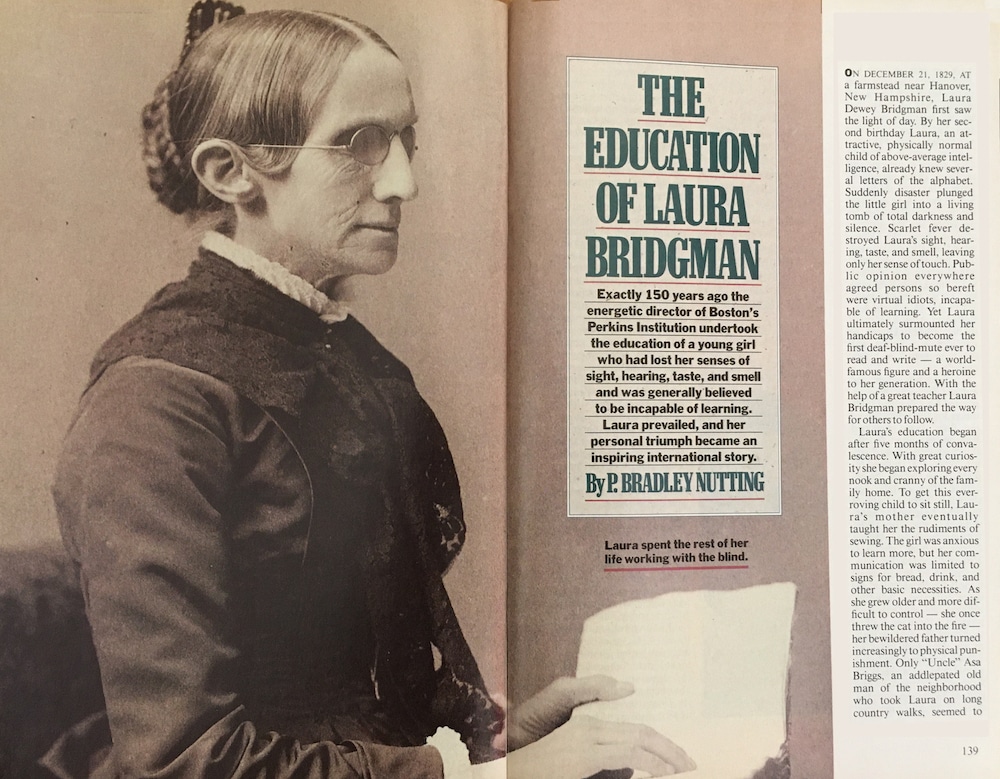

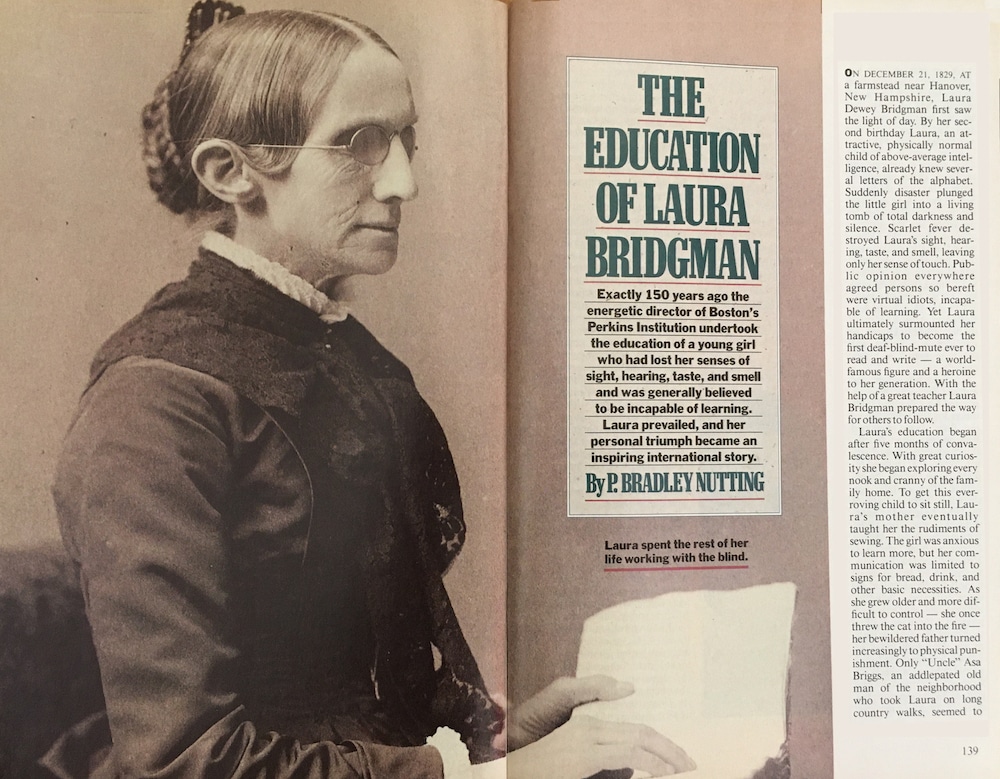

On December 21, 1829, at a farmstead near Hanover, New Hampshire, Laura Dewey Bridgman first saw the light of day. By her second birthday Laura, and attractive, physically normal child of above-average intelligence, already knew several letters of the alphabet. Suddenly disaster plunged the little girl into a living tomb of total darkness and silence. Scarlet fever destroyed Laura’s sight, hearing, taste, and smell, leaving only her sense of touch. Public opinion everywhere agreed persons so bereft were virtual idiots, incapable of learning. Yet Laura ultimately surmounted her handicaps to become the first deaf-blind-mute ever to read and write — a world-famous figure and a heroine to her generation. With the help of a great teacher Laura Bridgman prepared the way for others to follow.

Laura’s education began after five months of convalescence. With great curiosity she began exploring every nook and cranny of the family home. To get this ever-roving child to sit still, Laura’s mother eventually taught her the rudiments of sewing. The girl was anxious to learn more, but her communication was limited to signs for bread, drink, and other basic necessities. As she grew older and more difficult to control — she once threw the cat into the fire — her bewildered father turned increasingly to physical punishment. Only “Uncle” Asa Briggs, an addlepated old man of the neighborhood who took Laura on long country walks, seemed to have any rapport with her. Perhaps because she learned to fear her father, Laura was usually leery of males, but she did love two men: one was Asa Briggs; the other was Samuel Gridley Howe.

Howe, born in Boston in 1801, craved challenge and excitement. After graduating from Harvard Medical School in 1824, he sailed off for the Greek War of Independence. In the struggle against the Turks, Howe served as a physician, soldier, fund-raiser, and relief administrator, receiving a knighthood from the Greek king for six years of service. When Howe returned to Boston in April 1831 with the helmet of Lord Byron, he was literally a knight with armor in search of a crusade.

A cause was ready and waiting. The recently incorporated New England Institute for the Education of the Blind (soon renamed the Perkins Institution for the Blind) sorely needed a director. When the trustees offered Howe the job, he accepted immediately, for, though he knew nothing of the blind, he sensed an enormous challenge. After a brief trip overseas to observe French training methods, Howe returned to this country convinced that instruction of the blind should be more balanced, including intellectual, manual, and physical education. Rather than pampering the students as was frequently done in Europe, he believed self-reliance should be sought. With these goals in mind, in August 1832 he opened the doors of the first American school for the blind on Pearl Street in Boston.

As director, Howe was a whirlwind of activity. He developed teaching materials, recruited students, promoted fund-raising, and toured other states championing blind education. Within a short time Howe and the school were known throughout the nation.

Howe first heard of Laura Bridgman in the spring of 1837, and he left immediately for New Hampshire. Her parents, aware they could do little to help her, readily agreed that she should go off to school that fall. After several weeks of acclimation, Laura’s formal education commenced.

Although she knew some sign language, Howe rejected that approach completely. Instead he preferred to teach her letters and words “by the combination of which she might express her idea of anything.” Since braille was not yet in use, he pasted raised words on common objects. Once Laura learned the letters attached to spoon and key and so forth, Howe got her to match separated words with the objects, rewarding a correct response with a pat on the head. This was all rather rote, but step three was the giant one. Howe cut the letters apart, jumbled them, and presented Laura with a pile of letters and an object. After some faltering Laura suddenly understood that here was a precise way to communicate her thoughts.

Once Laura built up her vocabulary and learned all 26 letters, Howe taught her the “manual alphabet” or finger spelling used by some of the deaf. By January 1838 she was making rapid progress, “talking” in this fashion with Howe and other blind students and even with herself. When alone, Laura’s right hand would talk with her left, which corrected misspellings with a slap!

Although Howe now assigned other teachers to work with Laura, he dictated the curriculum, which included reading, spelling, writing, arithmetic, and geography, the latter aided by a giant relief globe specially imported from Germany. Howe insisted her lessons last no more than an hour and be interspersed with recreation. Since he also felt strongly about physical education, Laura’s teachers walked with her six miles daily and closely supervised her swimming and horseback riding.

This regimen went on for several years. Howe included a full account of Laura’s education in his annual reports to the Perkins trustees, which were then widely reprinted. Eventually, people began coming to the school to see the little girl with the green sash over her eyes; among them was Charles Dickens, who included an extensive discussion of Laura’s remarkable education in his 1847 travelogue, American Notes. Laura soon became so well known that girls on both sides of the Atlantic tied ribbon over their dolls’ eyes.

Laura’s formal education ceased at age 20. She was then sent home to stay, but life on the farm brought profound depression. Desperately needing a stimulating environment with many people to “talk” to, Laura soon returned to Perkins, remaining until her death in 1889. Since Howe stressed self-reliance, her life there was as active and useful as possible. An excellent seamstress, she made all her own clothes and fashioned lace and crocheted articles for sale. She also helped teach blind children to sew, proving a demanding instructor. Laura kept a journal, corresponded with family and acquaintances, and wrote poetry and prayers. Not only did she have many friends among the students, but she also met many visiting celebrities and politicians. A decided foe of slavery, the Mexican War, and capital punishment, Laura seldom hesitated to express her views on public policy.

Suffering from heart trouble, neuralgia, and malaria (acquired years before in Greece), Samuel Gridley Howe collapsed soon after the New Year and died on January 9, 1876. Several hours before the end, Laura entered the sickroom and kissed the unconscious Howe farewell.

Laura lived another 13 years and in that time passed on an important legacy of her own. She was to share rooms with a half-blind, hot-tempered young woman named Anne Sullivan. In 1880, at age 14, Anne, the daughter of poverty-stricken Irish immigrants, had talked her way out of the Tewksbury poorhouse into Perkins in desperate pursuit of a decent education. Anne came to know Laura well and learned the manual alphabet so that she might spell out all the latest gossip for her older roommate. This skill would prove more useful than Anne ever imagined.

In 1886 word reached Perkins that a little girl in Alabama who had lost both sight and hearing needed a teacher. Because of her experience with Laura, Anne was keenly aware the mission was no longer impossible; she accepted the assignment. As a symbolic passing of the mantle to the next generation, Laura Bridgman sewed the clothes for the doll Anne Sullivan took south to the new student. The child’s name was Helen Keller.

The following is an abridged version of “The Education of Laura Bridgman” by P. Bradley Nutting, October 1987.

On December 21, 1829, at a farmstead near Hanover, New Hampshire, Laura Dewey Bridgman first saw the light of day. By her second birthday Laura, and attractive, physically normal child of above-average intelligence, already knew several letters of the alphabet. Suddenly disaster plunged the little girl into a living tomb of total darkness and silence. Scarlet fever destroyed Laura’s sight, hearing, taste, and smell, leaving only her sense of touch. Public opinion everywhere agreed persons so bereft were virtual idiots, incapable of learning. Yet Laura ultimately surmounted her handicaps to become the first deaf-blind-mute ever to read and write — a world-famous figure and a heroine to her generation. With the help of a great teacher Laura Bridgman prepared the way for others to follow.

Laura’s education began after five months of convalescence. With great curiosity she began exploring every nook and cranny of the family home. To get this ever-roving child to sit still, Laura’s mother eventually taught her the rudiments of sewing. The girl was anxious to learn more, but her communication was limited to signs for bread, drink, and other basic necessities. As she grew older and more difficult to control — she once threw the cat into the fire — her bewildered father turned increasingly to physical punishment. Only “Uncle” Asa Briggs, an addlepated old man of the neighborhood who took Laura on long country walks, seemed to have any rapport with her. Perhaps because she learned to fear her father, Laura was usually leery of males, but she did love two men: one was Asa Briggs; the other was Samuel Gridley Howe.

Howe, born in Boston in 1801, craved challenge and excitement. After graduating from Harvard Medical School in 1824, he sailed off for the Greek War of Independence. In the struggle against the Turks, Howe served as a physician, soldier, fund-raiser, and relief administrator, receiving a knighthood from the Greek king for six years of service. When Howe returned to Boston in April 1831 with the helmet of Lord Byron, he was literally a knight with armor in search of a crusade.

A cause was ready and waiting. The recently incorporated New England Institute for the Education of the Blind (soon renamed the Perkins Institution for the Blind) sorely needed a director. When the trustees offered Howe the job, he accepted immediately, for, though he knew nothing of the blind, he sensed an enormous challenge. After a brief trip overseas to observe French training methods, Howe returned to this country convinced that instruction of the blind should be more balanced, including intellectual, manual, and physical education. Rather than pampering the students as was frequently done in Europe, he believed self-reliance should be sought. With these goals in mind, in August 1832 he opened the doors of the first American school for the blind on Pearl Street in Boston.

As director, Howe was a whirlwind of activity. He developed teaching materials, recruited students, promoted fund-raising, and toured other states championing blind education. Within a short time Howe and the school were known throughout the nation.

Howe first heard of Laura Bridgman in the spring of 1837, and he left immediately for New Hampshire. Her parents, aware they could do little to help her, readily agreed that she should go off to school that fall. After several weeks of acclimation, Laura’s formal education commenced.

Although she knew some sign language, Howe rejected that approach completely. Instead he preferred to teach her letters and words “by the combination of which she might express her idea of anything.” Since braille was not yet in use, he pasted raised words on common objects. Once Laura learned the letters attached to spoon and key and so forth, Howe got her to match separated words with the objects, rewarding a correct response with a pat on the head. This was all rather rote, but step three was the giant one. Howe cut the letters apart, jumbled them, and presented Laura with a pile of letters and an object. After some faltering Laura suddenly understood that here was a precise way to communicate her thoughts.

Once Laura built up her vocabulary and learned all 26 letters, Howe taught her the “manual alphabet” or finger spelling used by some of the deaf. By January 1838 she was making rapid progress, “talking” in this fashion with Howe and other blind students and even with herself. When alone, Laura’s right hand would talk with her left, which corrected misspellings with a slap!

Although Howe now assigned other teachers to work with Laura, he dictated the curriculum, which included reading, spelling, writing, arithmetic, and geography, the latter aided by a giant relief globe specially imported from Germany. Howe insisted her lessons last no more than an hour and be interspersed with recreation. Since he also felt strongly about physical education, Laura’s teachers walked with her six miles daily and closely supervised her swimming and horseback riding.

This regimen went on for several years. Howe included a full account of Laura’s education in his annual reports to the Perkins trustees, which were then widely reprinted. Eventually, people began coming to the school to see the little girl with the green sash over her eyes; among them was Charles Dickens, who included an extensive discussion of Laura’s remarkable education in his 1847 travelogue, American Notes. Laura soon became so well known that girls on both sides of the Atlantic tied ribbon over their dolls’ eyes.

Laura’s formal education ceased at age 20. She was then sent home to stay, but life on the farm brought profound depression. Desperately needing a stimulating environment with many people to “talk” to, Laura soon returned to Perkins, remaining until her death in 1889. Since Howe stressed self-reliance, her life there was as active and useful as possible. An excellent seamstress, she made all her own clothes and fashioned lace and crocheted articles for sale. She also helped teach blind children to sew, proving a demanding instructor. Laura kept a journal, corresponded with family and acquaintances, and wrote poetry and prayers. Not only did she have many friends among the students, but she also met many visiting celebrities and politicians. A decided foe of slavery, the Mexican War, and capital punishment, Laura seldom hesitated to express her views on public policy.

Suffering from heart trouble, neuralgia, and malaria (acquired years before in Greece), Samuel Gridley Howe collapsed soon after the New Year and died on January 9, 1876. Several hours before the end, Laura entered the sickroom and kissed the unconscious Howe farewell.

Laura lived another 13 years and in that time passed on an important legacy of her own. She was to share rooms with a half-blind, hot-tempered young woman named Anne Sullivan. In 1880, at age 14, Anne, the daughter of poverty-stricken Irish immigrants, had talked her way out of the Tewksbury poorhouse into Perkins in desperate pursuit of a decent education. Anne came to know Laura well and learned the manual alphabet so that she might spell out all the latest gossip for her older roommate. This skill would prove more useful than Anne ever imagined.

In 1886 word reached Perkins that a little girl in Alabama who had lost both sight and hearing needed a teacher. Because of her experience with Laura, Anne was keenly aware the mission was no longer impossible; she accepted the assignment. As a symbolic passing of the mantle to the next generation, Laura Bridgman sewed the clothes for the doll Anne Sullivan took south to the new student. The child’s name was Helen Keller.