Stories in the Snow | On the Trail with a Master Tracker

Eyes and ears sharpen when you’re exploring the Massachusetts woods with naturalist-tracker David Brown.

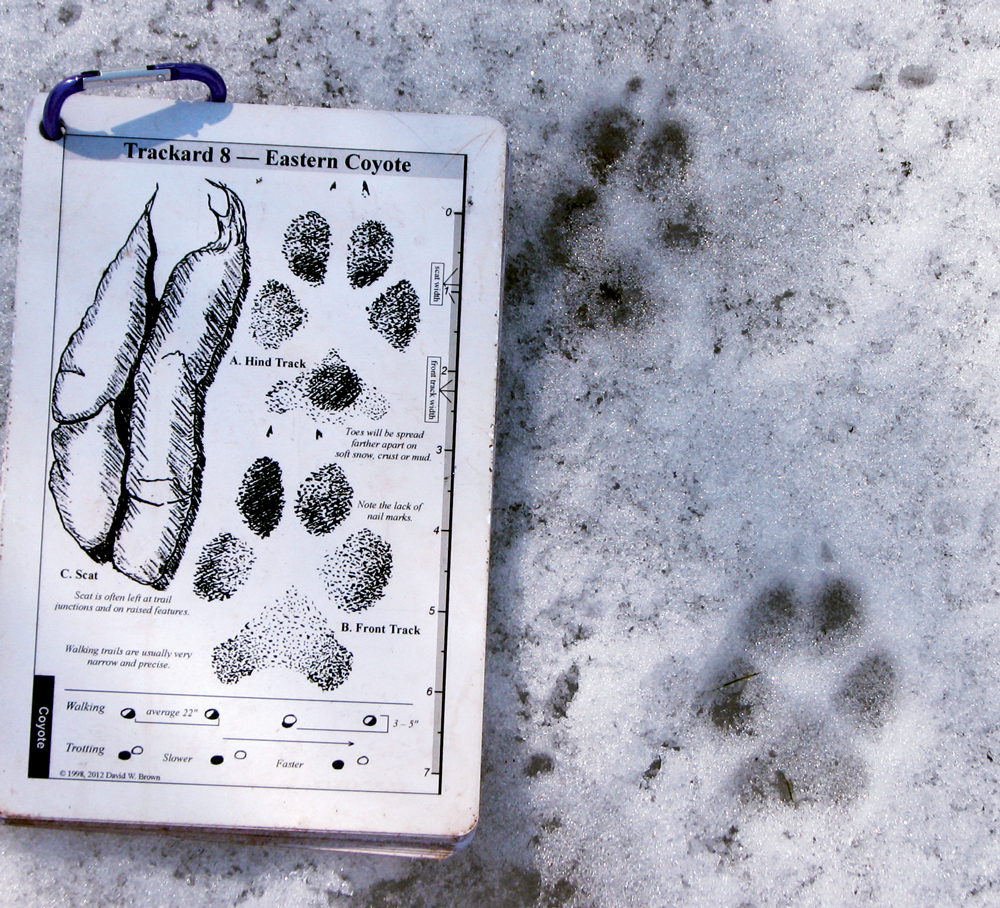

To a tracker’s keen eye, these footprints near the Quabbin Reservoir in central Massachusetts show the passage of not one but two Eastern coyotes, with the second animal following in the tracks of the first.

Photo Credit : Paul RezendesDress for the weather, I was instructed. And bring more clothes than you think you will need. Yes, it was predicted to be warmer than usual for a mid-February day in central Massachusetts, but deep woods can hold the chill. And tracking is a slow process.

It is also something I’ve always wanted to do. Fundamentally practical, it’s at the same time something magical, this ability to “read” the woods—something Merlin would have known. At its core, tracking is philosophical too. How to see more? Look more. The longer you look at snow, the less it is simply an expanse of white. And yes, it is an effortless storyteller, but the tale is not always easy to decipher. There are epics written right under your nose, in nature’s equivalent of invisible ink.

Photo Credit : Paul Rezendes

Two days before my introduction to David Brown, master tracker, and his Quabbin Trails program, my fellow participants and I get a heads-up email: 2-3 inches of snow on the ground, mostly crusted and durable. A brief reconnoiter this morning indicates that there are tracks and trails to occupy us.

Brown began his immersion decades ago, with renowned photographer and tracker Paul Rezendes, who wrote Tracking and the Art of Seeing. “Rezendes had the eye for it,” Brown tells me when we meet. “And a mind behind the eye.” Since then, in the 30-plus years he’s spent following wild creatures, this former English major and Vietnam vet has made his own significant contributions, writing books and offering workshops. Brown doesn’t just identify tracks—he’s invested in the stories they tell. What is this animal, what is it doing, is it walking or bounding, and how is it interacting with place? It’s the difference between knowing letters and being able to put them together to make words. And then sentences. Stories.

Photo Credit : Paul Rezendes

At 9:45 a.m., we gather at the Country Store in Petersham, Massachusetts, about an hour and a half west of Boston. The store sits off a town green that is stunning in its white-clapboard-ringed grandeur. The only obvious retail spot around, the store serves hot coffee, breakfast, and lunch and sells ruggedly pretty knitted things, along with a mix of local jams and pottery.

Brown is sitting in the far room, near a woodstove. He’s comfortable back here—it’s like a second living room—and several people call out a hello as they walk by. His silver beard is a rumpled version of Hemingway’s, overlooked by a pair of sharp blue eyes that are amplified by wire-rimmed glasses. He is rangy, self-contained. It turns out he has a dry sense of humor too, and a gift for stories.

My three expedition mates are already seated, and an easy camaraderie overhangs the group. Kristen, Gail, and Tim have all taken past workshops together. Spread across the table is an array of plaster casts of animal tracks: dog, bobcat, coyote. We study them over coffee, like a pop quiz without the pressure. “See this triangle in the middle?” Brown asks, pointing at one. The longer I stare, the more I can distinguish the difference between dog and coyote. The rounder prints belong to our domestic dog; the longer, skinnier ones are coyote. Like that, I catch a glimmer of this new language—a visual one that hangs on subtleties.

Photo Credit : courtesy of David Brown

Not so subtle? This damp morning that’s colder than predicted, temps in the 30s, when I’d been happily anticipating 40s. We head out and meet up at a parking lot beside a beautiful frozen pond (location undisclosed “to protect the wildlife,” says Kristen). The stillness is broken by the sound of backpacks being strapped on, gaiters cinching, and walking poles clicking open. Moments later, we’re already in the thick of it.

It’s a small track. Tim points out the toe definition, while Brown takes out his tape measure and instructs us to consider the habitat of evergreens. Consensus comes quickly: red squirrel. (These are practiced trackers, although Tim quickly clarifies, “David’s the veteran, we’re the assistant veterans.”) Steps later, near a path that connects two areas of water, we find beaver tracks and a little heap of something else. Gail sinks down, gives it a sniff. It’s castoreum, a gland excretion that beavers use to mark their turf. I, too, take a deep whiff. It smells spicy. Turns out, it’s used as a fixative in perfume. And in some schnapps.

And here are the trotting tracks of a river otter, crossing from one body of water to another. “Fellow travelers,” Tim comments softly. “You know, sometimes we’re three hours into a tracking session and still in sight of the parking lot.” At the beginning of this particular trek, we’ve also had ample opportunity to identify dog tracks (not as easy as you’d think). As I drop to my hands and knees to bring my nose closer to a pile of not-yet-frozen scat, I think of that injunction to do something new every day. “The niacin in dog food gives it the revolting smell,” says Brown, just a moment too late.

But then we wind farther into the woods, walking through a red oak and white pine forest, and now here are coyote tracks, 22 inches apart—the average gait, I learn. “In winter they’ll do anything to save energy,” says Brown, including walking in tracks laid down by others: humans, dogs, deer, anything that might give them a tiny edge to survive. “March and April are the hardest for them,” he says, as we journey deeper into the stillness. Small clumps of snow fall off the trees, and the ground is littered with the indents of these tiny snowballs, obscuring the tracks.

Photo Credit : courtesy of David Brown

Even so, we begin to find signs of fisher-cats. As anyone who owns a small pet can tell you, there’s a mythology surrounding these animals, often cast as the bogeymen of the forest. In reality, fishers look nothing like cats and are members of the weasel family. Also, out here there’s no judgment, only another set of prints to decipher. I pull out my Trackards—waterproof cards with life-size tracks that Brown designed to take on treks—and place the illustration alongside the mark in the snow. It’s a match. “Classic fisher tracks,” says Brown.

We see delicate princess pines, breaking through the snow. When my feet are freezing, Tim offers spare foot warmers and the gift of heat. I learn that fishers tend to circle around when hunting, whereas otters go straight. Brown tells us about a winter’s day he spent tracking a red fox up Mount Chocorua, painting a picture of what his eyes read in the snow. And when we find a small clump of crushed and torn branches, we spend minutes trying to decipher the story. In the end: “It’s a mystery,” Brown says, with a grin. “Sometimes it’s more-or-less guesswork; other times it’s guesswork.”

Toward the end of our trek, we come across the dancing steps of a ruffed grouse, a plump bird that “drums” on the air by beating its wings. It is a moment of shared delight, and a high note on which to end this cooling day, where hours have been spent imagining the intention of wild creatures. Where we’ve traced their stories. Brown nods his head, looks down. Looks up. Looks.

For more information about David Brown’s tracking workshops and other events, go to dbwildlife.com.

Annie Graves

A New Hampshire native, Annie has been a writer and editor for over 25 years, while also composing music and writing young adult novels.

More by Annie Graves