Before being executed on July 13, 1692, Elizabeth How, along with four other women who were hanged that day, endured trial proceedings that would soon become infamous. Since the early part of that year, the community in and around Salem, Massachusetts, had been roiled by a series of witch trials that threatened the very core of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Families and friendships were ripped apart in a crisis that eventually involved more than 400 people and led to the deaths of 25 innocent men, women, and children.

The wife of a farmer in nearby Topsfield and a mother of six, How (often spelled Howe) had been charged with “afflicting” several young women, including a 10-year-old girl who complained of being pricked by pins and suffering from mysterious fits. Acrimony defined the trial, as a number of How’s acquaintances and loved ones testified against her, overriding her denials and the voices of those who rose to her defense, including a prominent minister.

Now, more than 300 years after her trial and death, How is at the center of the Peabody Essex Museum’s newest exhibit,

The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning and Reclaiming, which runs through March 20, 2022. The exhibition features original 17th-century court documents and objects as well as two compelling contemporary responses by artists with direct ancestral links to the trials: fashion designer Alexander McQueen and photographer Frances F. Denny.

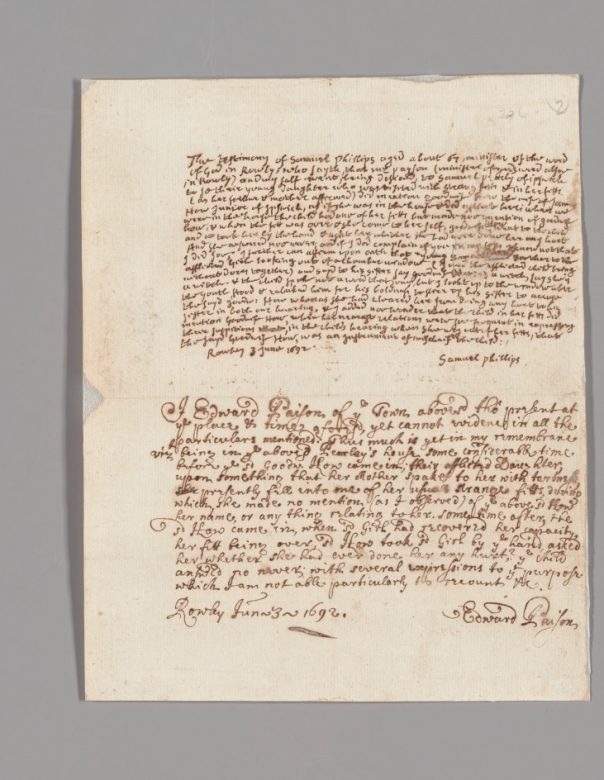

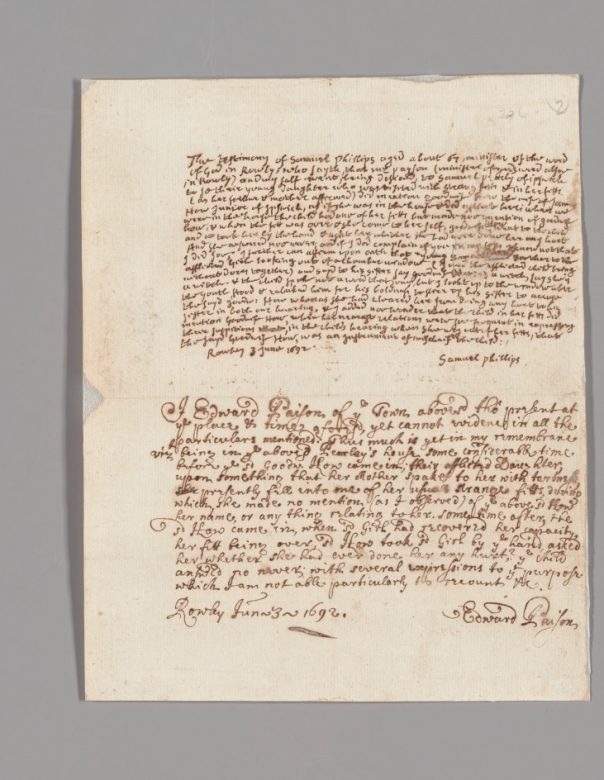

Among the historical documents featured in The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning and Reclaiming is the June 3, 1692, testimony of Samuel Phillips and Edward Payson in Elizabeth How’s trial.

Among the historical documents featured in The Salem Witch Trials: Reckoning and Reclaiming is the June 3, 1692, testimony of Samuel Phillips and Edward Payson in Elizabeth How’s trial.

Photo Credit : © Peabody Essex Museum

If there is a museum to tell this story, it’s PEM — and not just because it’s based in Salem. One of the largest art museums in North America, PEM is also home to the biggest collection of materials related to the Salem witch trials, including more than 500 original documents on deposit from the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

Coming on the heels of last year’s

The Salem Witch Trials 1692 — which marked for the first time in nearly three decades that the PEM had showcased artifacts from those holdings — the new exhibit continues to flesh out the real lives of the witch trials’ victims as well as highlight those who were brave enough to speak out against the proceedings. A selection of documents carefully chronicles How’s story, from the initial complaint and warrant for her arrest to her examination in court, testimony, indictment, execution, pardon, and final restitution to her family in 1712. In addition, there are historical furnishings and personal objects on display, including a trunk that once belonged to Jonathan Corwin, the magistrate who resided in what is today known as the Witch House.

“We’re still thinking about the witch trials more than 300 years later, and we’re still reckoning with the fallout from the trials and what it meant to these people and how we think about what those people experienced in 1692,” says Dan Lipcan, the Ann C. Pingree Director of PEM’s Phillips Library and one of the exhibition co-curators. “We want people to think about what it meant to be a witch in 1692 but also where they might see similar injustices today that run parallel to what was happening then.”

Indeed, the strength of this exhibit is that it’s not just a story about the past; it also makes several creative turns to fold in the present. More than three centuries after the witch trials, Alexander McQueen and Sarah Burton, now the creative director for the House of McQueen, paid a visit to Salem to research the story of Elizabeth How, a distant relative of the designer’s. The result was McQueen’s intensely personal and autobiographical fall/winter 2007 collection,

In Memory of Elizabeth How, 1692, represented here by selections including a form-fitting velvet “press sample” runway dress with a hand-sewn beaded starburst that radiates down the neckline and across the chest and shoulders.

Evening dress from Alexander McQueen’s fall/winter 2007 ready-to-wear collection, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem, 1692.

Evening dress from Alexander McQueen’s fall/winter 2007 ready-to-wear collection, In Memory of Elizabeth How, Salem, 1692.

Photo Credit : © Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, Massachusetts. Photography by Bob Packert.

“Alexander McQueen found tremendous creative energy in learning about this chapter in his family history,” says exhibition co-curator Paula Richter. “For him, it was this creative spark in which he was able to draw on many threads related to both the 17th-century trials here in Massachusetts as well as other trials across Europe.”

The final piece of the exhibit chronicles what it means to reclaim the term “witch,” a word that for centuries has been used to silence and control women. As a descendent of both accusers and the accused, photographer Frances F. Denny set out on a journey to discover modern-day witches for her project

Major Arcana: Portraits of Witches in America. Along the way, she encountered healers, artists, and tarot readers representing a vast spectrum of identities and spiritual practices.

For the PEM exhibition, curators selected 13 portraits and accompanying personal essays from Denny’s project, each revealing a fascinating glimpse into the contemporary spiritual movement. One of those featured, Karen Rose, explains that in embracing her identity she was able to further connect with those who came before her.

A portrait of Karen Rose of Brooklyn, New York, from Frances F. Denny’s Major Arcana: Portraits of Witches in America project.

A portrait of Karen Rose of Brooklyn, New York, from Frances F. Denny’s Major Arcana: Portraits of Witches in America project.

Photo Credit : Frances F. Denny 2020

“I never considered myself a witch,” writes Karen Rose of Brooklyn, New York. “I consider myself the descendent of healers. The granddaughter of medicine people. My grandfather and my grandmother knew spirit, plants, and how to heal, and they passed this on to me. They never called themselves anything. I realize now that many would call me a witch because of my knowledge of things that are intangible and not always seen. I am cool with it. The witches of Africa are powerful and influence change in great ways. I’m about that.”

It’s this careful weaving together of the past with present that helps build a larger story for how we can all move forward into the future, says Lydia Gordon, PEM’s associate curator and exhibition co-curator.

“What happened in the 17th century is so tragic,” she says, “with all of these injustices and accusations and lives lost for nothing. By bringing the history into the present day, we can look to see how far we’ve come, but also remember where we came from. So with these incredible documents and timelines and all this other stuff, we can create a chorus of reckoning so that we can continue to move forward with a better understanding of the past so that don’t make the same kind of errors.

“So much of what we tried to do — not just with the contemporary, but with the historic — was really bring out people’s voices, these deeply personal accounts, that tell of their experiences,” she continues. “I think and I hope it creates a chorus of reckoning so that we can … develop a greater understanding and empathy for each other so we can use our voices to speak out against injustices now.”

The Peabody Essex Museum is located at East India Square, 161 Essex St., Salem, MA. It is currently open 10 a.m.–5 p.m. on Thursdays, Saturdays, and Sundays, and 10 a.m.–8 p.m. on Fridays and holiday Mondays. Reserve tickets in advance at pem.org/tickets or by calling 978-542-1511. For details on PEM’s safety protocols, go to pem.org/safety. To listen to a riveting PEM podcast episode about the Salem witch trials, go to pem.org/pemcast.