Old Home Days: A New England Tradition

I returned to my hometown this week. The Walpole, New Hampshire, “Old Home Days” committee had invited me to give a reading at the library. I arrived early enough to catch the end of the parade and let the familiar landmarks settle in: the big shade trees and stately white Colonial homes lining Main Street, […]

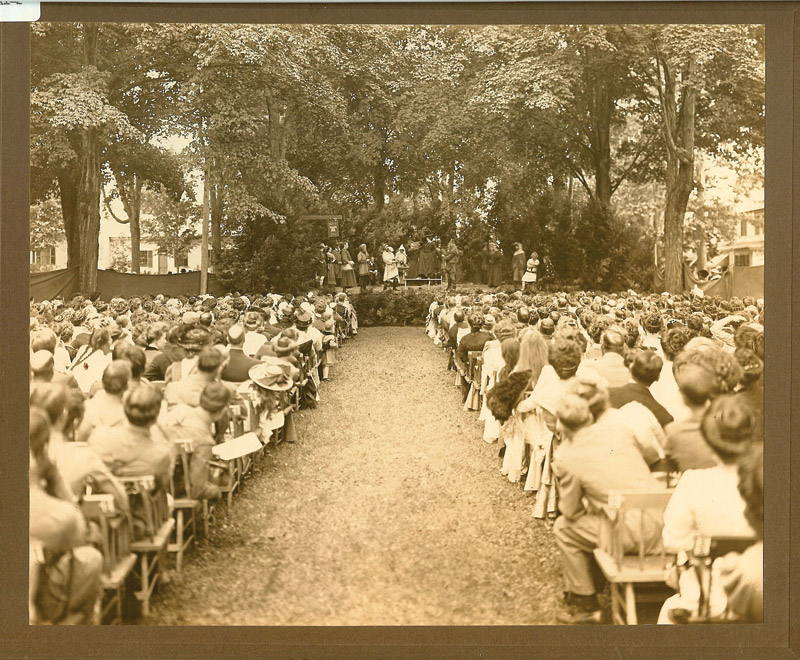

Many towns around New England put on versions of the celebration every summer, usually for a day or a weekend. Walpole’s has grown so elaborate that it takes place just once every three years. This year, some 20 subcommittees organized everything from the opening block party on Wednesday afternoon to the final Sunday-night performance of the Walpole Players’ You Can’t Take It With You. T-shirt sales, fireworks, chicken barbeque, antique car show, talent show, pet show, 5K race, basketball shootout, band concert, dance, shortcake social, parade–each had a squadron of volunteers and months in the planning behind it, along with part of the event’s $10,000 budget.

The whole thing stretches over the length of time that the inventor of the ritual, Frank Rollins of New Hampshire, envisioned back in 1897 when he created an official Old Home Week Association and lobbied towns around the state to take part. Rollins feared that New Hampshire’s small towns were dying. He saw the farms and villages emptying out to better-paying factory jobs in the cities and to the promise of prosperity and easier farming in the South and Midwest. In the old homesteads collapsing into cellar holes and brush reclaiming the fields, Rollins saw New Hampshire’s place in America’s future fading, as well. Taking office as governor in 1899, he responded with a nationwide appeal to native sons and daughters to return home, to rediscover the wholesomeness of small-town life amid an increasingly impersonal urbanized culture. He hoped that once lured back home, many would choose to stay. The whole idea was a public-relations campaign, built around nostalgia and a longing for some lost sense of community.

In truth, I felt some of some of what Rollins intended, although I still live in the state, just an hour or so from Walpole. After the library reading, I walked past the little restaurant that Tom Murray started the year after we graduated from high school, and wandered around the booths and exhibits on the town’s broad common. I heard kids’ voices ringing out from the ballfield behind the brown stone church, where we used to play pick-up baseball games during the Sunday-evening band concerts. We’d stand while the band played “The Star-Spangled Banner,” holding our hats over our hearts, imagining we were pros. Toward the end of the afternoon, I took a drive, passing trout streams where I’d learned to fish, felt rushes of memory, felt the pull that Governor Rollins had once banked on.

But to be honest, in the throng of people crowding the common and the village square, I recognized only a small percentage of the faces, and almost none, like me, who had returned to visit. Walpole, like so many towns in New England, has reversed the emptying out that threatened their existence a century ago. What threatens the town’s wholesomeness today is growth: not too many cellar holes, but too many houses.

Most of those attending Old Home Days were residents new to the town. Most of them commute to jobs somewhere else. The celebration is intended to bring them together. Chuck Bingaman, who co-chaired the publicity committee with his wife, Sue, moved to Walpole six years ago from Illinois. He told me that working on the Old Home Days celebration has allowed him to get to know all kinds of people around town, folks with whom he likely wouldn’t have interacted otherwise. The work has given him a powerful, geographical sense of community, not just the selective community of like-minded friends and acquaintances he’d found in the various places he’d lived. It has given him the old-fashioned feeling of being home. He’s not planning to move again.

Ironically, Old Home Days still serves its original purpose, but from an opposite direction. Its power of nostalgia and connection no longer entices former residents to return, but current ones to stay.