Georgia O’Keeffe in Portland

As often seems to happen with the inspiration for museum exhibitions, the idea for Georgia O’Keeffe and the Camera: The Art of Identity occurred to Portland Museum of Art curator Susan Danly as she was looking at photographs in the museum’s own collection. The Portland Museum of Art happens to own three portraits of the […]

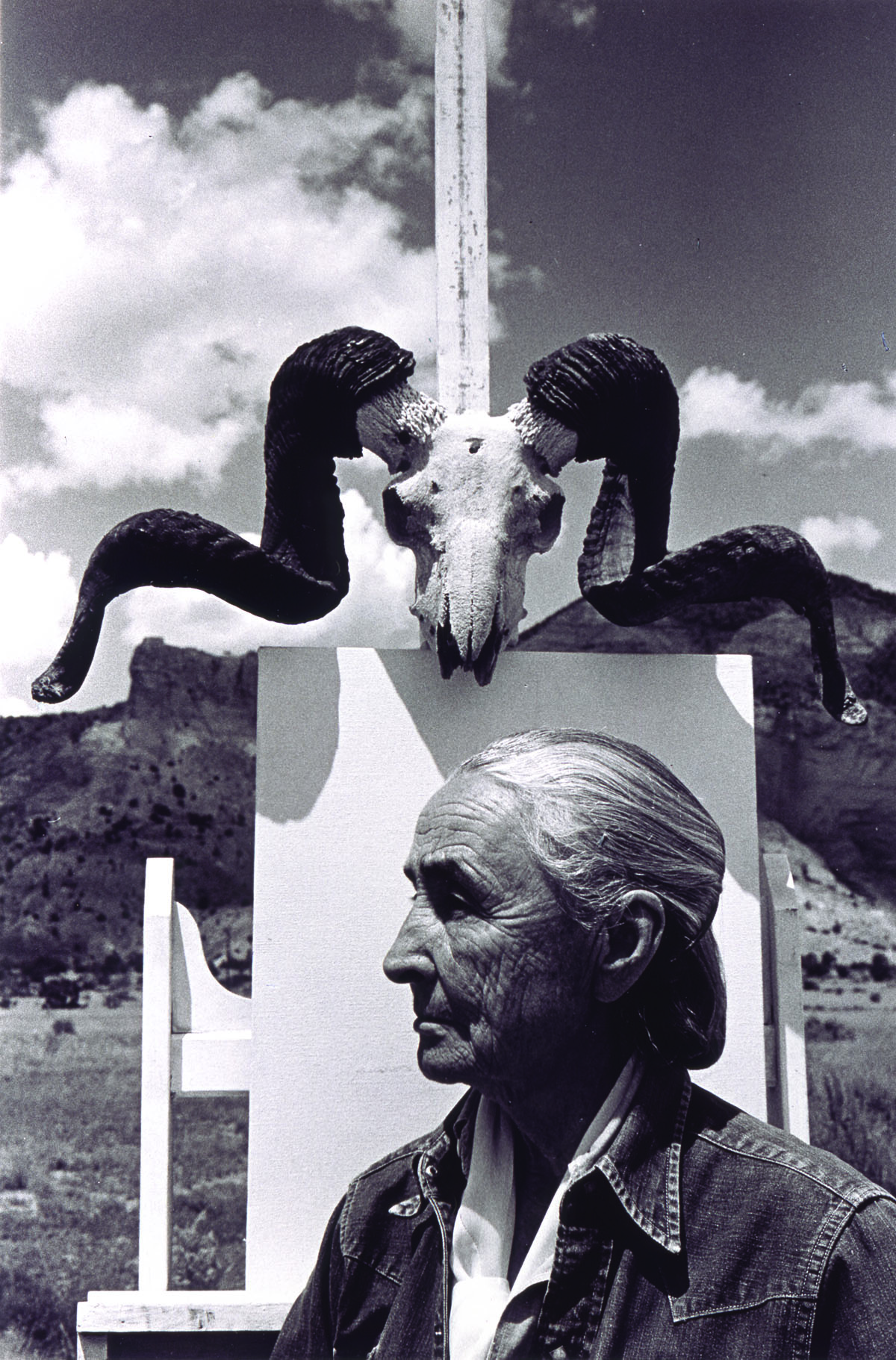

“Georgia O’Keeffe, Ghost Ranch, New Mexico” by Arnold Newman, 1968, gelatin silver print

As often seems to happen with the inspiration for museum exhibitions, the idea for Georgia O’Keeffe and the Camera: The Art of Identity occurred to Portland Museum of Art curator Susan Danly as she was looking at photographs in the museum’s own collection. The Portland Museum of Art happens to own three portraits of the desert queen of modern art — “Georgia O’Keeffe Seated Among Her Props, 1952” by George Daniell, “Georgia O’Keeffe at Ghost Ranch, 1963” by Todd Webb, and “Georgia O’Keeffe, Ghost Ranch, New Mexico, 1968” by Arnold Newman – both because O’Keeffe was one of the most photographed artists of the 20th century and because all three photographers spent time in Maine.

What interested Susan Danly was “How photographs have shaped our ideas about O’Keeffe and her work.” Georgia O’Keeffe and the Camera thus manifested itself as an exhibition of 60 photographs of the artist and her environs together with 18 works by O’Keeffe herself. Undertaken in collaboration with the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico, the O’Keeffe exhibition features photographs of the artist taken between 1917 and 1979, the earliest made by Alfred Stieglitz, the most recent by Andy Warhol — a remarkable span of both time and temperament.

Georgia O’Keeffe was born in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, in 1887 and died in Santa Fe, New Mexico, in 1986 at the age of 99. She first met legendary photographer and art dealer Alfred Stieglitz in 1916 when he exhibited her early work at his 291 Gallery in New York City. Stieglitz quickly became O’Keeffe’s mentor, dealer, lover and, ultimately, in 1924, her husband. Between 1917 and 1937, Stieglitz took some 350 photographs of O’Keeffe, a body of work that included portraits, nudes and abstractions and chronicled O’Keeffe’s evolution from shy, plain, vulnerable young woman to serious, mature, self-possessed artist.

O’Keeffe’s scandalous affair with the much older and married Stieglitz and the very sensual nudes Stieglitz took of O’Keeffe inclined viewers and critics to read sexuality into her paintings, large close-ups of flowers and leaves tending to be read as female genitalia. None of Stieglitz’s O’Keeffe nudes are included Georgia O’Keeffe and the Camera, curator Susan Danly, feeling that relationship had been explored before, instead selecting Stieglitz photographs that contain or illuminate his wife’s art.

Few artists are more associated with a landscape than Georgia O’Keeffe is with the New Mexican desert around the village of Abiquiu where she lived year-round in her elegant and elemental Ghost Ranch from 1949 until her death. There she reigned as the high priestess of modern art, as dramatically black and white, bone dry, aged, wise, impassive, and regal as her only rival for the throne, sculptor Louise Nevelson, who ruled Manhattan if nothing else.

O’Keeffe cultivated the image of a dowager desert recluse, yet she seemed to attract photographers like flies. Ansel Adams was among the first to move in on Stieglitz’s favorite subject once the great man became too ill in 1937 to photograph his wife. The photographers who followed read like a who’s who of 20th century portrait photography — Philippe Halsman, Yousuf Karsh, Arnold Newman, Irving Penn, Warhol. The celebrity portrait photographers were attracted to O’Keeffe’s fame, but the photographers who knew her best were her New Mexico neighbors Eliot Porter and Todd Webb, both of whom photographed O’Keeffe extensively.

The exhibition also features photographs by photojournalists such as Balthazar Korab who photographed Ghost Ranch for a 1965 House Beautiful and John Loengard who created a 1968 photo essay on O’Keeffe for Life. Each photographer has a slightly different take on the chiaroscuro world and persona of O’Keeffe, Korab’s architectural interiors providing the only color relief from the black and white imagery. O’Keeffe seems to have husbanded color for her paintings, sucking it out of the rest of her life.

The woman evoked in all of these photographs is a sad-eyed nun of an artist, ancient and wise, yet somehow humorless. Just once I would love to see a photograph of Georgia O’Keeffe smiling and laughing, but, except for a few wry smirks in the early Ansel Adams’ photographs, she seemed never to drop the mask of identity she fashioned for herself with the help of the camera.

Georgia O’Keeffe and the Camera: The Art of Identity, June 12 to September 7, Portland Museum of Art, Seven Congress Square, Portland ME, 207-775-6148, www.portlandmuseum.org. September 26 to February 1, 2009, The Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Santa Fe, NM, www.okeeffemuseum.org. Yale University Press has published the handsome exhibition catalogue, $45 hardcover, $29.95 soft.

Edgar Allen Beem

Take a look at art in New England with Edgar Allen Beem. He’s been art critic for the Portland Independent, art critic and feature writer for Maine Times, and now is a freelance writer for Yankee, Down East, Boston Globe Magazine, The Forecaster, and Photo District News. He’s the author of Maine Art Now (1990) and Maine: The Spirit of America (2000).

More by Edgar Allen Beem