Magazine

Remembering Theodor Geisel | Who Was Dr. Seuss?

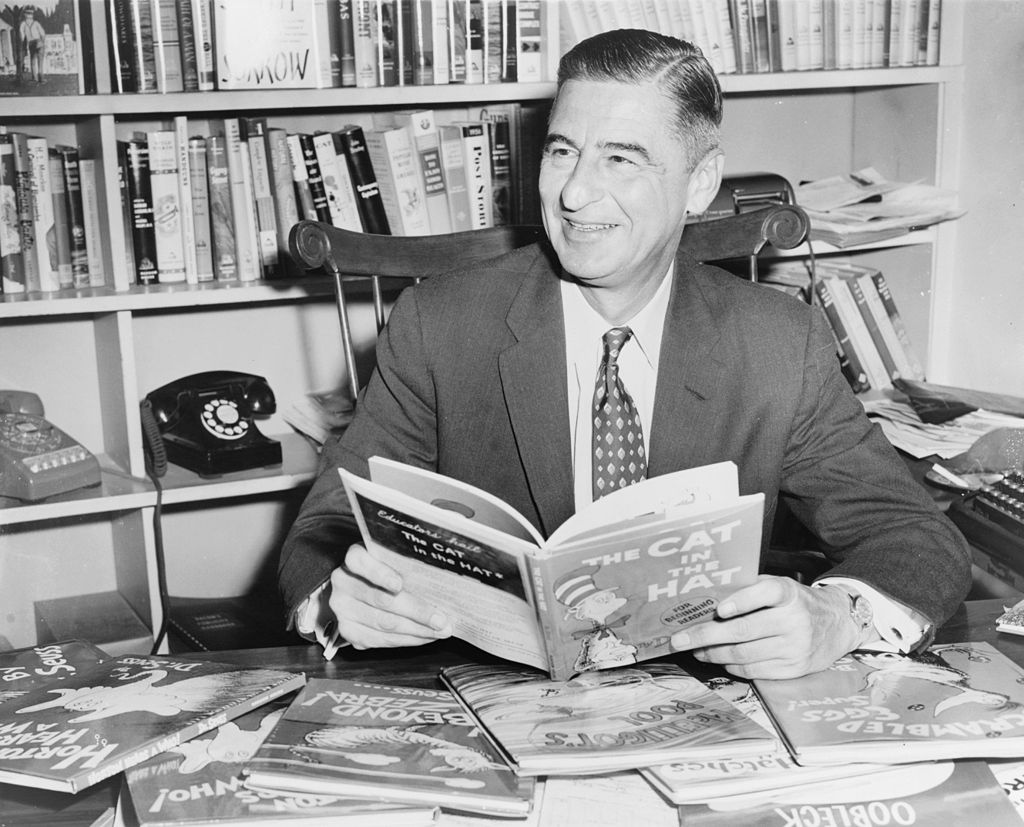

While the world mourned the death of Dr. Seuss, the man who created the Grinch and the Cat in the Hat, in Springfield, MA, they mourned for Theodor Geisel.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

***

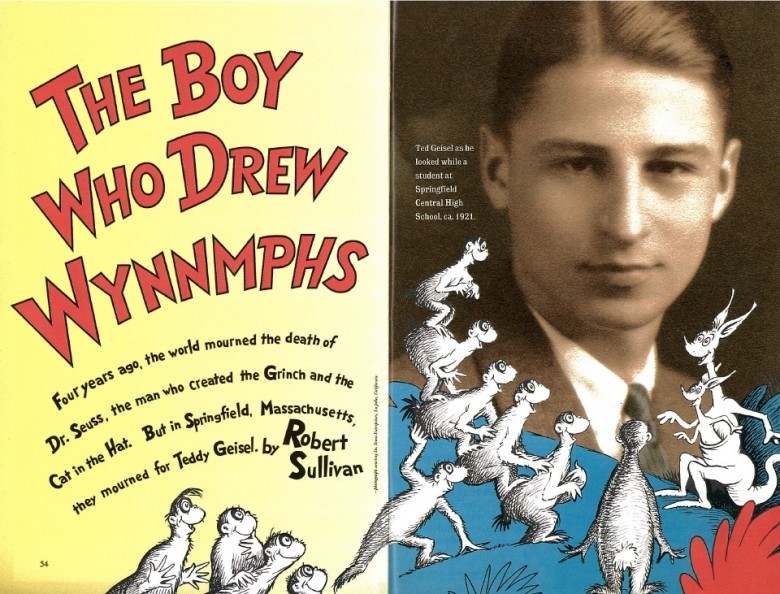

In the first decade of this century, the city-town of Springfield in western Massachusetts personified America’s industrial dream. Set in the lush and lovely Connecticut River valley, it was a vital thing — an engine hitting on all cylinders, blowing off steam, churning out product, making money. In this town, on March 2, 1904, a boy, Theodor, was born into the prosperous clan of German beer barons known as the Geisels. He grew up at 74 Fairfield Street, off the larger, much grander Sumner Avenue. Six blocks away was the Springfield Zoo in Forest Park. All the first models for Dr. Seuss’s wondrous men-a-gerie lived there. “That zoo,” said the eventual creator of Zooks, Yooks, and Barbaloots, “was where I learned whatever I know about animals.” Ted’s father, T. R., once held a world record in riflery, and each morning he’d go for target practice in the 700-acre Forest Park. Ted tagged along. He’d help with the targets for awhile, then would steal off to sketch the animals. “I was always drawing — with pencils, pens, crayons, or anything. Nearly always, it was animals. Goofy-looking ones. My mother overindulged me and seemed to be saying, ‘Everything you do is great, just go ahead and do it.’ ” Henrietta Seuss, like T. R. Geisel, was of German descent, though her family had been in Springfield generations longer than T. R.’s. The two shared a love for the outdoors and an astonishing aptitude with firearms. At six feet and nearly 200 pounds, the large, strong, serenely pretty Henrietta was a crack shot, nearly matching her husband trophy for trophy. Ted was devoted to his mother, and she responded with unceasing praise and encouragement. When Ted decided that riflery wasn’t for him, that was fine with Henrietta. When Ted complained that he hated exercising at the school gym, Henrietta defended him to his father. When Ted drew animals on the attic walls with the crayons and pencils he kept by his bedside, that was fine, too. When Ted showed his mother a sketch of a beast from the zoo — a beast with ears hanging down to its feet and beyond — Henrietta said that was wonderful. When Ted announced that the animal was called “a Wynnmph,” she said, of course it is!

Photo Credit : Wikimedia Commons

***

Ted left Springfield in 1921 and went on to thrive at Dartmouth. At the college’s humor magazine, the Jack O’Lantern, “Seuss” was born. “The night before Easter of my senior year there were ten of us gathered in my room at the Randall Club,” Geisel recalled much later. “We had a pint of gin for ten people. But Pa Randall called Chief Rood, the chief of police, and he himself in person raided us. We were all put on probation for defying Prohibition — and especially on Easter evening.” As a consequence of his punishment, Geisel could no longer function as editor of the magazine. The spring 1925 edition carried a suspiciously high number of unsigned cartoons. Moreover, there were sketches by several brand-new artists: “L. Burbank,” “Thos. Mott Osborne,” “D. G. Rossetti,” “T. Seuss,” and one by “Seuss.” In Geisel’s early career as a magazine humorist and advertising-copy artist, his byline underwent permutations — “Theo. Seuss 2nd,” “Dr. Theophrastus Seuss,” “Dr. Theodophilus Seuss, Ph.D, I.Q., H2S04” — but it never again returned to “Ted Geisel.” Geisel started to recede even as Seuss enlarged. When a children’s book entitled And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street by “Dr. Seuss” appeared in 1937, only in Springfield did people say, “Remember Teddy Geisel? That’s his book.” For another half century the folks in Springfield would be saying, some 47 more times, “Teddy Geisel’s got another book out.”***

Ted was lured back in 1986 when, on the occasion of Springfield’s 350th anniversary, more than 600 area children wrote letters begging for a visit. He was presented with a sign — “Geisel Grove” — that had been hung in Forest Park where he had once picnicked with his family. He visited Mulberry Street. He visited 74 Fairfield Street and his boyhood bedroom, where he once fell asleep to the howling of wolves at the zoo. “Behind that wallpaper,” he said to his wife, Audrey, “you’ll find holes I gouged in the wall with a pencil.” In his sister’s old room across the hall, two young brothers — eight-year-old Joel and five-year-old Aaron Senez — were waiting. He told them about his mother and father and of growing up in this very house. He showed them which way the beds had faced, so they could face theirs the same way. “Just stopped by to make sure you’re taking proper care of the house,” he said before leaving. “We’re taking care of it!” they replied. Are you a fan of Theodor Geisel, aka Dr. Seuss?