History

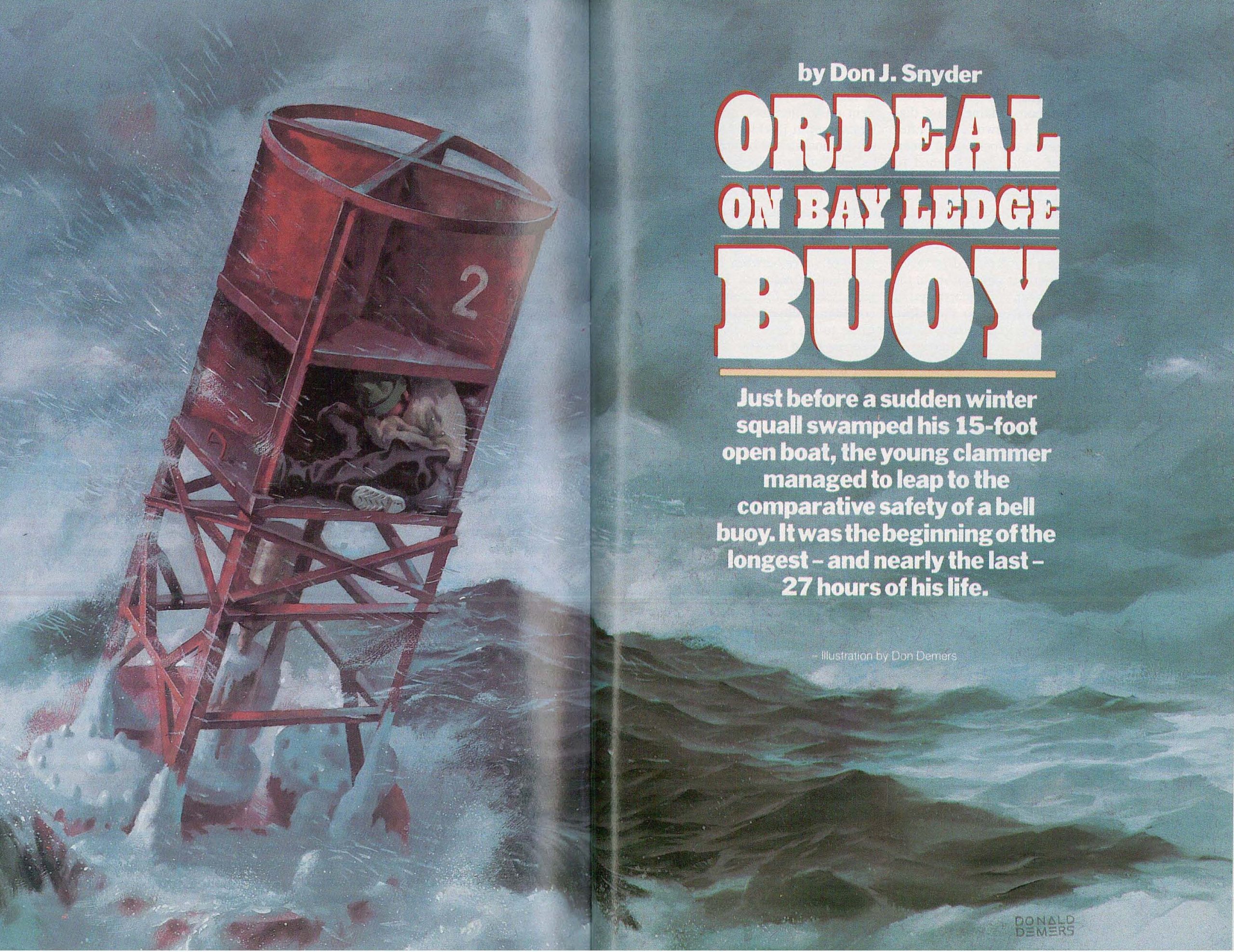

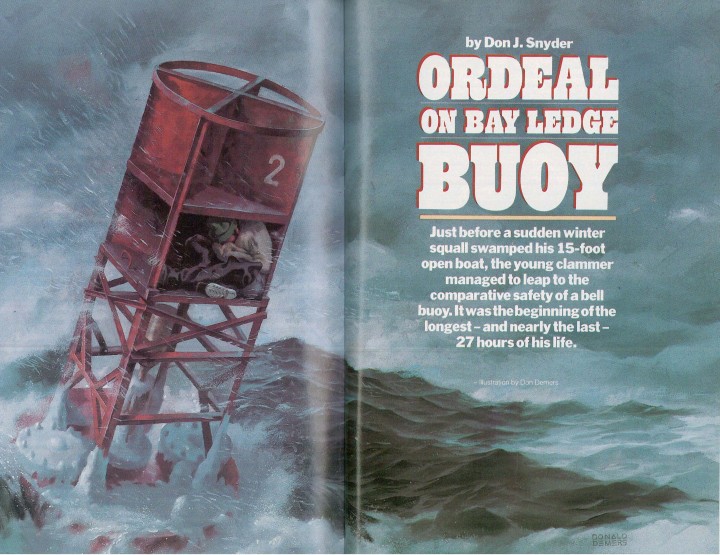

Ordeal on Bay Ledge Buoy

Just before a sudden winter squall swamped his 15-foot open boat, the young clammer managed to leap to the comparative safety of the Bay Ledge Buoy. It was the beginning of the longest — and nearly the last — 27 hours of his life. Sunday morning. January 15, began as any working day for […]

Photo Credit:

Sunday morning. January 15, began as any working day for Robert “Bo” Curtis, a 25-year-old Waldoboro, Maine, clam digger. He awoke just after seven o’clock, fixed a cup of coffee, and listened to the scratchy, monotone voice on his weather radio declaring the latest forecast for the waters of Penobscot Bay. Bo, a likable young man with a sandy beard and a smart-like-a-fox gleam in his blue eyes, comes from a long line of clam diggers. He knew there was nothing unusual about the forecast — winds out of the northwest at five to 15 knots; seas one to three feet; waves five to seven seconds apart; visibility one to three miles in snow flurries. It was cold, about eight degrees, standard for this time of year; when you dig clams in the winter, you expect to be cold.

Bo left the house around nine o’clock, driving 15 miles north on Route 1 and pulling his 15-foot fiberglass boat, Drifty II, and 40-horsepower motor on a trailer behind. He stopped once for gasoline, then went on to the dock at the Black Pearl Restaurant in Rockland harbor where he put his boat in just before ten o’clock. He looked out across the harbor, and though it was snowing lightly, he could see several miles to the Rockland lighthouse. He had a 30-minute trip ahead of him, approximately 12 miles straight east from the dock to the Fox Island Thoroughfare, a body of water between North Haven Island and Vinalhaven Island. This was prize territory for clam digging and Bo considered himself fortunate to have a license to dig there. Only 11 licenses had been awarded this year, six of them to residents. Bo had paid $100 and received license number II.

Having dug clams since he was four years old, he had been to the Fox Island Thoroughfare hundreds of times. Extremely swift currents there keep the flats free from ice, and this meant Bo would be able to dig clams right through the winter and to set aside some money by June when he was getting married. He had already rented a house on North Haven, and his idea was to live right there so he could work every single day, as many tides as possible. This morning Drifty II was loaded with clothing and other provisions he would drop off at the rented house after the day’s work.

Walter Brochu, Bo’s partner for five years, could not make the trip today; he was stuck at home trying to fix some pipes that had frozen in the recent cold spell. He expected to receive a telephone call from Bo late in the afternoon after he’d finished working the last tide.

Bo had also promised to call his fiancée’s house at noon. He knew Denise would be concerned about his going out alone today, and he thought about her as he started up the motor and turned away from the dock. He was wearing a chamois shirt she had made for him and his normal layers of work clothes: black rubber hipboots, insulated underwear, dungarees, a hooded sweat shirt, sweater, down vest, wool hat, one regular pair of socks and a pair of thick boot socks.

Heading out, he braced himself against the blast of icy sea spray, lit a cigarette, and pointed his bow directly east. He had a sense of well-being this morning: he was glad for another day of work, another day that would bring him closer to June. He felt he had a lot to look forward to.

Very suddenly the evenness of this day began to come unraveled. The cadence of his motion on the water, the pattern of his reflexes, even the flow of his thoughts were jarred by an abrupt shift in the rhythm of the sea. A squall had blown up and he was caught in the center of it.

He tells what happened next: “The sea smoke got real bad all of a sudden, and the visibility dropped down to practically nothing. I took out my compass and tried to keep an easterly course, but then the waves came up, monster waves, eight to 12 feet high. I was halfway out, and I knew if I tried to turn around anyone of those waves could capsize me.”

He battled to keep his bow in the waves. The wind was full of ice and he could not see more than a few yards in front of him. He started taking in a lot of water.

“With each wave I’d give her more throttle and shoot through, but the bow would go completely under water. I turned around and saw that my stern was under water, too. I had only about three feet of boat that wasn’t submerged. I tried to concentrate on keeping the bow in the waves, trying to plow through them and come out the other side. I was bailing with a Clorox scoop, but it wasn’t doing much good.

“The ocean, the whole world seemed suddenly to have been heaved upside down. Enormous black waves rose up in front of him, then towered over him, then pounded his boat. He could make no easterly progress against the force of the storm. He was helplessly running with the wind and the waves, and with each passing minute he was being carried farther off course, farther toward the open sea where he knew there was no chance of surviving.

He expected at any second to have his boat thrown over in the waves and to be plunged into water so cold that he would have lasted only a few minutes. Then through the blowing snow and sea smoke he spotted a dark shape, like an apparition, coming straight towards him. It was the black outline of a bell buoy. “I knew I had to grab hold of it if I could,” Bo relates. ” It was my only hope. I got up alongside and one wave knocked my boat right into it. As I got one foot on the buoy, another wave came in from behind and took the boat right out from under me. I dropped into the water up to the tops of my boots. Somehow I got up on the buoy. My boat was about four feet away. I knew I couldn’t go in the water for it. I watched it being carried away by the waves until finally I could see just the outline of the stern. I kept seeing it, or thought I did, but it was gone.”

Bo had no way of knowing then that he had climbed onto the Bay Ledge Buoy five miles south of Vinalhaven. It was the last thing to grab hold of before Matinicus Rock and open sea in the Gulf of Maine. Described by the Coast Guard as a 1962-type standard buoy, the Bay Ledge Buoy stands eight feet high from the waterline to its peak and is eight feet across the base. It is equipped with a light and a whistle mechanism, neither of which were functioning.

As the buoy tilted and dipped beneath him, Bo grabbed hold of an iron bar, kicked the ice off the base for better footing, and clambered up four feet where he quickly jammed himself in between the fin-like radar reflectors, a space two and a half feet high, and three feet, one and a half inches wide which narrowed into a pieshaped wedge with an iron bar welded across its circumference.

He settled into this space, stuffed his wet gloves in the corners to block out the wind, then looping his belt around the iron bar, he fashioned a handle which he held onto while the buoy rolled in the mounting swells. He took a look at his watch. It was 10:45. It seemed impossible that so much had happened in so short a time. Time had meant nothing while he was struggling against the storm; but now, already aching with cold, he realized that every minute on this buoy would pass like an hour.

Thirty minutes went by. Then through the screeching winds he heard an unbelievable sound, the sound of an engine. “I couldn’t see through the snow, but I started yelling anyway. Then I made out a boat; it looked like a scallop boat. I waved my hands. I waved my vest. I yelled. The storm was so bad I knew everybody would be down below, but I waved anyway. I knew it might be my last chance.”

A few seconds later this chance vanished. The boat disappeared.

He wondered how long the storm would continue, how long it would be before Denise, or somebody, realized he was in trouble. He thought about the Coast Guard searching for him. At first this thought consoled him, but then it turned to an agonizing apprehension: “I got to thinking that if they came looking for me, they’d find my boat and they’d figure I was dead. I believe in a Supreme Being and I guess I started praying then. I just said, if it’s my time to go I’ll accept it. But I didn’t want them to find my empty boat and give up on me. I thought about dying and somebody finding me frozen to the buoy … I couldn’t handle that thought.”

After an hour he had begun to shiver uncontrollably. His feet and hands had lost all feeling. The buoy was swaying violently in the seas. He was wedged so tightly against it that he knew he could hold on, but what was the sense of holding on if he couldn’t keep from freezing? He turned all his thoughts and instincts to the single question of how he could relieve the cold. “I had my Bic lighter in my pants pocket and I tore off one of the rubber straps from my boots and lit it. I held it under my sweater to block the wind. I took my arms out of the sleeves and pulled myself into a ball inside the sweater. I put my head inside too. The smoke was bad from the burning rubber, but there was heat inside! So I took off one boot and I tore it along the seams with my teeth and ripped the rubber into strips to burn.”

Burning this first rubber strip he discovered that he had transformed his sweater into a furnace of sorts. Like a turtle he had to keep sticking his head out for gulps of air and he couldn’t breathe the smoke, but slowly the ice that was caked on his face and head melted and he managed to dry out his clothes.

He burned one strip every two hours. His feet remained numb and his hands were so cold that he had to hold the lighter between his teeth and one end of the rubber strip under his armpit so it could reach the flame. He knew that the longer he remained like this, the greater the chance he would lose his feet and hands to frostbite, but the warmth of his fire reassured him. “I figured I wasn’t going to freeze to death. I might lose parts of me, but I wasn’t going to die here as long as I had something to burn. I had just bought a new lighter the day before and it was working fine. I kept thinking about this, thinking that I was going to make it. I thought about Denise a lot. I thought about everything I’d done that day, the time I’d left home, the time I’d left the dock, the time I’d climbed onto the buoy. With night coming on I had to keep my mind working. I had to keep thinking so I’d stay awake. The kind of feeling I had when it got dark was like someone was drawing a bead on me with a shotgun. What are you going to do? Duck? Try to talk them out of it? Run? There was nowhere for me to go.”

It was Bo’s partner, Walter Brochu, who telephoned the Coast Guard Station in Rockland. ”I’d expected him at the house by five at the latest, and when he didn’t call me by then I knew he was in some kind of trouble. I told the Coast Guard that the buoys were the first place to check. I figured if he was able to tie onto a buoy he might try that.”

Boatswain’s Mate Robert Adams also had the buoys in mind when he got the search underway at the Rockland station. It was just after six o’clock when he started out in a 44-foot motor lifeboat, but halfway across the harbor he lost his radar and had to turn back for another vessel. By 8:30 P.M. he got underway again, and by now a Coast Guard helicopter from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, was nearing the search area and was in radio contact. Adams explains his strategy: “My idea was to do a shoreline search with the helicopter going out ahead of me. The winds were out of the northwest at 15 to 20 knots with higher gusts. There was very poor visibility with freezing spray. It was pretty bad. I was hoping he’d make it to shore.”

After searching for six hours neither Adams nor the helicopter personnel had seen any trace of Bo Curtis.

But he had seen them. “I heard the helicopter a couple of hundred feet above me. lt was around midnight. I knew they wouldn’t be able to see me through the snow, and I was cramped up in the buoy. I yelled, but they flew off.”

Adams explains that the helicopter shined a spotlight on the Bay Ledge Buoy but saw nothing. Seeing no boat tied up to it, and not expecting Bo to be this far from the Fox Island Thoroughfare, the helicopter went on.

When the helicopter disappeared in the storm, Bo’s hopes drained. With the buoy reeling beneath him, he tried to concentrate on the thought that it might be back. He had been on the buoy 11 hours, and now he knew there were people out looking for him.

He kept burning his rubber strips. “I didn’t sleep at all. I never lost consciousness. It was cold. You can’t believe how cold it was. I bit down on my lighter to keep from shivering. And the buoy was really swaying. I’d seen these buoys turn right over in bad storms. For a couple of hours it was swaying so bad that my face was only four inches from the ocean at times. That was hard to take.” When Boatswain’s Mate Adams returned to the Coast Guard station to be relieved at 3:45 A.M., he found Bo’s mother, sister, and Denise waiting there. “I reported in, got a cup of coffee, and then went to talk to them. I showed them the charts and pointed out where we were searching. I really thought that he was gone, but I didn’t let on. I also didn’t want to give them any false hopes.”

The Coast Guard cutter Yankton out of Portland also joined in the search. By eleven o’clock the next morning Master Chief William Boddy of the Jonesport Coast Guard Station got underway in an 82-foot patrol boat, The Point Hannon.

“Under the circumstances,” recalls Boddy, “I didn’t think there was any chance he’d be found alive.”

By now the storm had passed, and Bo had made it through his worst hours. “Just before dawn, when it got coldest, 1 wondered if it might be easier to jump in and get it over with. I didn’t know how much more suffering I’d have to put up with before somebody found me. What kept me going was the thought of Denise. I was daydreaming; I kept thinking Denise was coming to get me. Then I’d realize it wasn’t so. But once the sun came up my spirits got better. I was playing with the ducks to pass the time. They’d come right up to me and then I’d growl and they’d scatter. I was about to bum my last strip of rubber when I saw a boat.”

It was two o’clock in the afternoon when the officer on watch aboard The Point Hannon spotted something on the Bay Ledge Buoy. “He thought it was a bird at first,” says Boddy. ” Then he looked through the binoculars and saw a man waving back. It was hard to believe — that was our man.”

Bo remembers those moments when the Coast Guard boat pulled alongside the buoy. ” I tried to stand up, and when I did I pulled a big patch of skin off my rear end. I was frozen to the buoy. They saw that I was black all over; my hair was black and my face, and they thought it was bad frostbite. But it was just the soot from burning my boots. I was covered with soot. When they got close and asked me how I felt, I said, ‘I feel fine. I’d sure like a coffee.’ ”

From the patrol boat Bo was transferred to the helicopter. He was flown to Bangor and taken to the Eastern Maine Medical Center where doctors were amazed at his condition. His hands and feet had suffered frostbite, but he had kept himself warm enough so that he would recover completely. Two days later, after telling his story to reporters who crowded into a conference room at the hospital, he was released. When asked where he and Denise planned to go for their honeymoon, he replied, “Someplace warm.” On the front page of the Bangor Daily News there was a three column photograph of Bo flicking his Bic lighter for the press with hands that were swollen and discolored. Responding to reporters’ questions, his mother said her son was a smart boy.

It was early last February when I met Bo Curtis for the first time. He wore a baby-blue mitten on his right hand which was still swollen and black around the fingernails. “Other than that,” Bo said, awkwardly lighting a cigarette with his left hand, “I feel real good. I ought to be clamming pretty soon.” He told me he had gone to Denise’s parents’ house to recuperate and when I asked him how long it had taken to recover he said, “Oh, I spent a day or. the couch, and then I was up and around pretty good.”

Along the dock in Rockland near the Black Pearl, we passed several fishermen working on their boats. “Hey, how you making it?” one of them called out. “You thawed out yet, Bo?”

Excerpt from “’Ordeal on Bay Ledge Buoy,” Yankee Magazine, January 1985.

Sunday morning. January 15, began as any working day for Robert “Bo” Curtis, a 25-year-old Waldoboro, Maine, clam digger. He awoke just after seven o’clock, fixed a cup of coffee, and listened to the scratchy, monotone voice on his weather radio declaring the latest forecast for the waters of Penobscot Bay. Bo, a likable young man with a sandy beard and a smart-like-a-fox gleam in his blue eyes, comes from a long line of clam diggers. He knew there was nothing unusual about the forecast — winds out of the northwest at five to 15 knots; seas one to three feet; waves five to seven seconds apart; visibility one to three miles in snow flurries. It was cold, about eight degrees, standard for this time of year; when you dig clams in the winter, you expect to be cold.

Bo left the house around nine o’clock, driving 15 miles north on Route 1 and pulling his 15-foot fiberglass boat, Drifty II, and 40-horsepower motor on a trailer behind. He stopped once for gasoline, then went on to the dock at the Black Pearl Restaurant in Rockland harbor where he put his boat in just before ten o’clock. He looked out across the harbor, and though it was snowing lightly, he could see several miles to the Rockland lighthouse. He had a 30-minute trip ahead of him, approximately 12 miles straight east from the dock to the Fox Island Thoroughfare, a body of water between North Haven Island and Vinalhaven Island. This was prize territory for clam digging and Bo considered himself fortunate to have a license to dig there. Only 11 licenses had been awarded this year, six of them to residents. Bo had paid $100 and received license number II.

Having dug clams since he was four years old, he had been to the Fox Island Thoroughfare hundreds of times. Extremely swift currents there keep the flats free from ice, and this meant Bo would be able to dig clams right through the winter and to set aside some money by June when he was getting married. He had already rented a house on North Haven, and his idea was to live right there so he could work every single day, as many tides as possible. This morning Drifty II was loaded with clothing and other provisions he would drop off at the rented house after the day’s work.

Walter Brochu, Bo’s partner for five years, could not make the trip today; he was stuck at home trying to fix some pipes that had frozen in the recent cold spell. He expected to receive a telephone call from Bo late in the afternoon after he’d finished working the last tide.

Bo had also promised to call his fiancée’s house at noon. He knew Denise would be concerned about his going out alone today, and he thought about her as he started up the motor and turned away from the dock. He was wearing a chamois shirt she had made for him and his normal layers of work clothes: black rubber hipboots, insulated underwear, dungarees, a hooded sweat shirt, sweater, down vest, wool hat, one regular pair of socks and a pair of thick boot socks.

Heading out, he braced himself against the blast of icy sea spray, lit a cigarette, and pointed his bow directly east. He had a sense of well-being this morning: he was glad for another day of work, another day that would bring him closer to June. He felt he had a lot to look forward to.

Very suddenly the evenness of this day began to come unraveled. The cadence of his motion on the water, the pattern of his reflexes, even the flow of his thoughts were jarred by an abrupt shift in the rhythm of the sea. A squall had blown up and he was caught in the center of it.

He tells what happened next: “The sea smoke got real bad all of a sudden, and the visibility dropped down to practically nothing. I took out my compass and tried to keep an easterly course, but then the waves came up, monster waves, eight to 12 feet high. I was halfway out, and I knew if I tried to turn around anyone of those waves could capsize me.”

He battled to keep his bow in the waves. The wind was full of ice and he could not see more than a few yards in front of him. He started taking in a lot of water.

“With each wave I’d give her more throttle and shoot through, but the bow would go completely under water. I turned around and saw that my stern was under water, too. I had only about three feet of boat that wasn’t submerged. I tried to concentrate on keeping the bow in the waves, trying to plow through them and come out the other side. I was bailing with a Clorox scoop, but it wasn’t doing much good.

“The ocean, the whole world seemed suddenly to have been heaved upside down. Enormous black waves rose up in front of him, then towered over him, then pounded his boat. He could make no easterly progress against the force of the storm. He was helplessly running with the wind and the waves, and with each passing minute he was being carried farther off course, farther toward the open sea where he knew there was no chance of surviving.

He expected at any second to have his boat thrown over in the waves and to be plunged into water so cold that he would have lasted only a few minutes. Then through the blowing snow and sea smoke he spotted a dark shape, like an apparition, coming straight towards him. It was the black outline of a bell buoy. “I knew I had to grab hold of it if I could,” Bo relates. ” It was my only hope. I got up alongside and one wave knocked my boat right into it. As I got one foot on the buoy, another wave came in from behind and took the boat right out from under me. I dropped into the water up to the tops of my boots. Somehow I got up on the buoy. My boat was about four feet away. I knew I couldn’t go in the water for it. I watched it being carried away by the waves until finally I could see just the outline of the stern. I kept seeing it, or thought I did, but it was gone.”

Bo had no way of knowing then that he had climbed onto the Bay Ledge Buoy five miles south of Vinalhaven. It was the last thing to grab hold of before Matinicus Rock and open sea in the Gulf of Maine. Described by the Coast Guard as a 1962-type standard buoy, the Bay Ledge Buoy stands eight feet high from the waterline to its peak and is eight feet across the base. It is equipped with a light and a whistle mechanism, neither of which were functioning.

As the buoy tilted and dipped beneath him, Bo grabbed hold of an iron bar, kicked the ice off the base for better footing, and clambered up four feet where he quickly jammed himself in between the fin-like radar reflectors, a space two and a half feet high, and three feet, one and a half inches wide which narrowed into a pieshaped wedge with an iron bar welded across its circumference.

He settled into this space, stuffed his wet gloves in the corners to block out the wind, then looping his belt around the iron bar, he fashioned a handle which he held onto while the buoy rolled in the mounting swells. He took a look at his watch. It was 10:45. It seemed impossible that so much had happened in so short a time. Time had meant nothing while he was struggling against the storm; but now, already aching with cold, he realized that every minute on this buoy would pass like an hour.

Thirty minutes went by. Then through the screeching winds he heard an unbelievable sound, the sound of an engine. “I couldn’t see through the snow, but I started yelling anyway. Then I made out a boat; it looked like a scallop boat. I waved my hands. I waved my vest. I yelled. The storm was so bad I knew everybody would be down below, but I waved anyway. I knew it might be my last chance.”

A few seconds later this chance vanished. The boat disappeared.

He wondered how long the storm would continue, how long it would be before Denise, or somebody, realized he was in trouble. He thought about the Coast Guard searching for him. At first this thought consoled him, but then it turned to an agonizing apprehension: “I got to thinking that if they came looking for me, they’d find my boat and they’d figure I was dead. I believe in a Supreme Being and I guess I started praying then. I just said, if it’s my time to go I’ll accept it. But I didn’t want them to find my empty boat and give up on me. I thought about dying and somebody finding me frozen to the buoy … I couldn’t handle that thought.”

After an hour he had begun to shiver uncontrollably. His feet and hands had lost all feeling. The buoy was swaying violently in the seas. He was wedged so tightly against it that he knew he could hold on, but what was the sense of holding on if he couldn’t keep from freezing? He turned all his thoughts and instincts to the single question of how he could relieve the cold. “I had my Bic lighter in my pants pocket and I tore off one of the rubber straps from my boots and lit it. I held it under my sweater to block the wind. I took my arms out of the sleeves and pulled myself into a ball inside the sweater. I put my head inside too. The smoke was bad from the burning rubber, but there was heat inside! So I took off one boot and I tore it along the seams with my teeth and ripped the rubber into strips to burn.”

Burning this first rubber strip he discovered that he had transformed his sweater into a furnace of sorts. Like a turtle he had to keep sticking his head out for gulps of air and he couldn’t breathe the smoke, but slowly the ice that was caked on his face and head melted and he managed to dry out his clothes.

He burned one strip every two hours. His feet remained numb and his hands were so cold that he had to hold the lighter between his teeth and one end of the rubber strip under his armpit so it could reach the flame. He knew that the longer he remained like this, the greater the chance he would lose his feet and hands to frostbite, but the warmth of his fire reassured him. “I figured I wasn’t going to freeze to death. I might lose parts of me, but I wasn’t going to die here as long as I had something to burn. I had just bought a new lighter the day before and it was working fine. I kept thinking about this, thinking that I was going to make it. I thought about Denise a lot. I thought about everything I’d done that day, the time I’d left home, the time I’d left the dock, the time I’d climbed onto the buoy. With night coming on I had to keep my mind working. I had to keep thinking so I’d stay awake. The kind of feeling I had when it got dark was like someone was drawing a bead on me with a shotgun. What are you going to do? Duck? Try to talk them out of it? Run? There was nowhere for me to go.”

It was Bo’s partner, Walter Brochu, who telephoned the Coast Guard Station in Rockland. ”I’d expected him at the house by five at the latest, and when he didn’t call me by then I knew he was in some kind of trouble. I told the Coast Guard that the buoys were the first place to check. I figured if he was able to tie onto a buoy he might try that.”

Boatswain’s Mate Robert Adams also had the buoys in mind when he got the search underway at the Rockland station. It was just after six o’clock when he started out in a 44-foot motor lifeboat, but halfway across the harbor he lost his radar and had to turn back for another vessel. By 8:30 P.M. he got underway again, and by now a Coast Guard helicopter from Cape Cod, Massachusetts, was nearing the search area and was in radio contact. Adams explains his strategy: “My idea was to do a shoreline search with the helicopter going out ahead of me. The winds were out of the northwest at 15 to 20 knots with higher gusts. There was very poor visibility with freezing spray. It was pretty bad. I was hoping he’d make it to shore.”

After searching for six hours neither Adams nor the helicopter personnel had seen any trace of Bo Curtis.

But he had seen them. “I heard the helicopter a couple of hundred feet above me. lt was around midnight. I knew they wouldn’t be able to see me through the snow, and I was cramped up in the buoy. I yelled, but they flew off.”

Adams explains that the helicopter shined a spotlight on the Bay Ledge Buoy but saw nothing. Seeing no boat tied up to it, and not expecting Bo to be this far from the Fox Island Thoroughfare, the helicopter went on.

When the helicopter disappeared in the storm, Bo’s hopes drained. With the buoy reeling beneath him, he tried to concentrate on the thought that it might be back. He had been on the buoy 11 hours, and now he knew there were people out looking for him.

He kept burning his rubber strips. “I didn’t sleep at all. I never lost consciousness. It was cold. You can’t believe how cold it was. I bit down on my lighter to keep from shivering. And the buoy was really swaying. I’d seen these buoys turn right over in bad storms. For a couple of hours it was swaying so bad that my face was only four inches from the ocean at times. That was hard to take.” When Boatswain’s Mate Adams returned to the Coast Guard station to be relieved at 3:45 A.M., he found Bo’s mother, sister, and Denise waiting there. “I reported in, got a cup of coffee, and then went to talk to them. I showed them the charts and pointed out where we were searching. I really thought that he was gone, but I didn’t let on. I also didn’t want to give them any false hopes.”

The Coast Guard cutter Yankton out of Portland also joined in the search. By eleven o’clock the next morning Master Chief William Boddy of the Jonesport Coast Guard Station got underway in an 82-foot patrol boat, The Point Hannon.

“Under the circumstances,” recalls Boddy, “I didn’t think there was any chance he’d be found alive.”

By now the storm had passed, and Bo had made it through his worst hours. “Just before dawn, when it got coldest, 1 wondered if it might be easier to jump in and get it over with. I didn’t know how much more suffering I’d have to put up with before somebody found me. What kept me going was the thought of Denise. I was daydreaming; I kept thinking Denise was coming to get me. Then I’d realize it wasn’t so. But once the sun came up my spirits got better. I was playing with the ducks to pass the time. They’d come right up to me and then I’d growl and they’d scatter. I was about to bum my last strip of rubber when I saw a boat.”

It was two o’clock in the afternoon when the officer on watch aboard The Point Hannon spotted something on the Bay Ledge Buoy. “He thought it was a bird at first,” says Boddy. ” Then he looked through the binoculars and saw a man waving back. It was hard to believe — that was our man.”

Bo remembers those moments when the Coast Guard boat pulled alongside the buoy. ” I tried to stand up, and when I did I pulled a big patch of skin off my rear end. I was frozen to the buoy. They saw that I was black all over; my hair was black and my face, and they thought it was bad frostbite. But it was just the soot from burning my boots. I was covered with soot. When they got close and asked me how I felt, I said, ‘I feel fine. I’d sure like a coffee.’ ”

From the patrol boat Bo was transferred to the helicopter. He was flown to Bangor and taken to the Eastern Maine Medical Center where doctors were amazed at his condition. His hands and feet had suffered frostbite, but he had kept himself warm enough so that he would recover completely. Two days later, after telling his story to reporters who crowded into a conference room at the hospital, he was released. When asked where he and Denise planned to go for their honeymoon, he replied, “Someplace warm.” On the front page of the Bangor Daily News there was a three column photograph of Bo flicking his Bic lighter for the press with hands that were swollen and discolored. Responding to reporters’ questions, his mother said her son was a smart boy.

It was early last February when I met Bo Curtis for the first time. He wore a baby-blue mitten on his right hand which was still swollen and black around the fingernails. “Other than that,” Bo said, awkwardly lighting a cigarette with his left hand, “I feel real good. I ought to be clamming pretty soon.” He told me he had gone to Denise’s parents’ house to recuperate and when I asked him how long it had taken to recover he said, “Oh, I spent a day or. the couch, and then I was up and around pretty good.”

Along the dock in Rockland near the Black Pearl, we passed several fishermen working on their boats. “Hey, how you making it?” one of them called out. “You thawed out yet, Bo?”

Excerpt from “’Ordeal on Bay Ledge Buoy,” Yankee Magazine, January 1985.

Enjoyed several of these writings and as we have over 70 inches of snow where I lived, I could really use the laugh!

Is there any follow up on how Bo & Denise are now?

Hi Trish,

We couldn’t find any mention of Bo and Denise in our archives, so it’s unlikely that a follow-up story was ever written.