The Long Silence of Lizzie Borden | Yankee Classic

What do you do when you’re Lizzie Borden and everyone thinks you got away with murder? We revisit the case in this 1996 Yankee classic.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanNow a Yankee classic, this article about the life of Lizzie Borden in the years following the 1892 murders of her father and stepmother was first published in 1996. What did Lizzie Borden do after the trial? Read on to find out.

The Long Silence of Lizzie Borden

On June 2, 1927, an obituary appeared in the Fall River, Massachusetts, Daily Globe. It described a 68-year-old woman who had died of pneumonia in her home the day before. She was a member of one of the old Fall River families, it said, and her life had been “quiet” and “retired.” She took pride in her home and her charities and loved animals, nature, and rides in the country. At the end of the article the writer mentions, as if the event had been long forgotten, that the deceased had been tried and acquitted of the 1892 murder of her father and stepmother. It was the kindest thing the Daily Globe had printed about Lizzie Borden in 35 years.

* * *

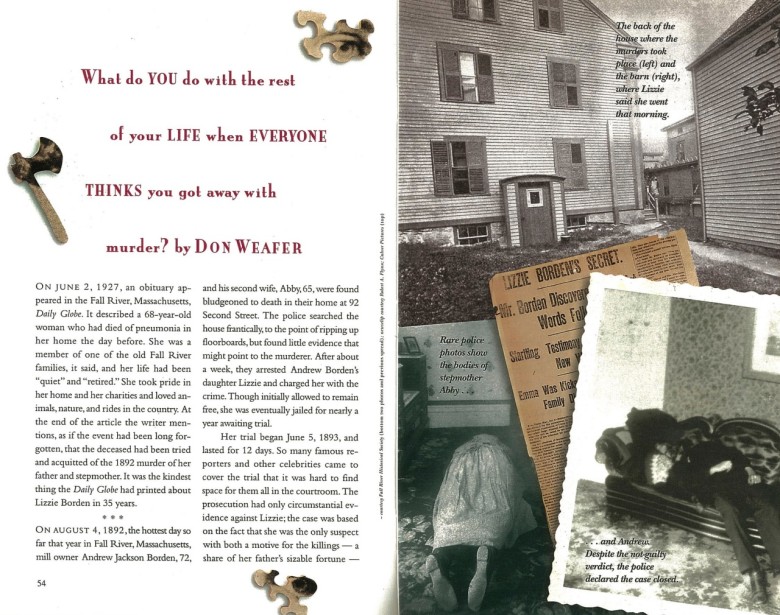

On August 4, 1892, the hottest day so far that year in Fall River, Massachusetts, mill owner Andrew Jackson Borden, 72, and his second wife, Abby, 65, were found bludgeoned to death in their home at 92 Second Street. The police searched the house frantically, to the point of ripping up floorboards, but found little evidence that might point to the murderer. After about a week, they arrested Andrew Borden’s daughter Lizzie Borden and charged her with the crime. Though initially allowed to remain free, she was eventually jailed for nearly a year awaiting trial.

Her trial began June 5, 1893, and lasted for 12 days. So many famous reporters and other celebrities came to cover the trial that it was hard to find space for them all in the courtroom. The prosecution had only circumstantial evidence against Lizzie; the case was based on the fact that she was the only suspect with both a motive for the killings – a share of her father’s sizable fortune – and the opportunity to carry them out. District Attorney Hosea Morrill Knowlton withdrew almost completely from the trial, plagued by doubts about the strength of his case.

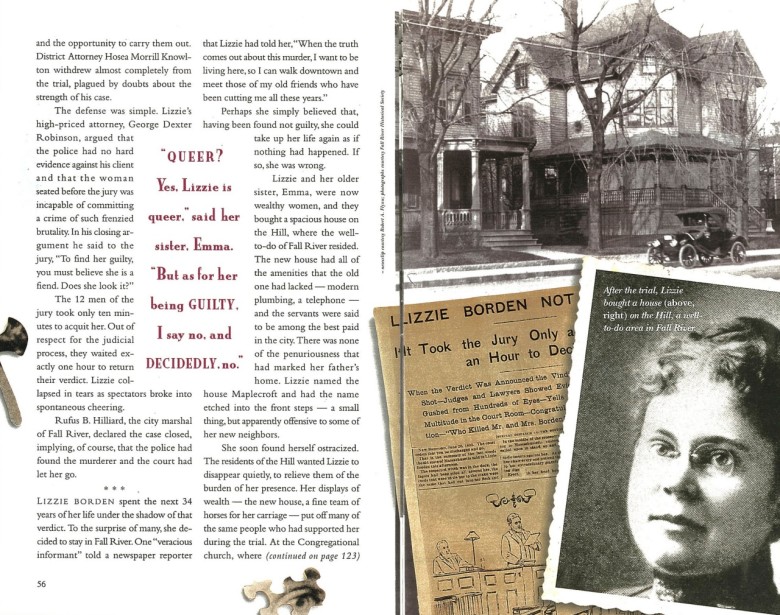

The defense was simple. Lizzie’s high-priced attorney, George Dexter Robinson, argued that the police had no hard evidence against his client and that the woman seated before the jury was incapable of committing a crime of such frenzied brutality. In his closing argument he said to the jury, “To find her guilty, you must believe she is a fiend. Does she look it?” The 12 men of the jury took only ten minutes to acquit her. Out of respect for the judicial process, they waited exactly one hour to return their verdict. Lizzie collapsed in tears as spectators broke into spontaneous cheering.

Rufus B. Hilliard, the city marshal of Fall River, declared the case closed, implying, of course, that the police had found the murderer and the court had let her go.

* * *

Lizzie Borden spent the next 34 years of her life under the shadow of that verdict. To the surprise of many, she decided to stay in Fall River. One “veracious informant” told a newspaper reporter that Lizzie had told her, “When the truth comes out about this murder, I want to be living here, so I can walk downtown and meet those of my old friends who have been cutting me all these years.”

Perhaps she simply believed that, having been found not guilty, she could take up her life again as if nothing had happened. If so, she was wrong.

Lizzie Borden and her older sister, Emma Borden, were now wealthy women, and they bought a spacious house on the Hill, where the well to-do of Fall River resided. The new house had all of the amenities that the old one had lacked – modern plumbing, a telephone – and the servants were said to be among the best paid in the city. There was none of the penuriousness that had marked her father’s home. Lizzie named the house Maplecroft and had the name etched into the front steps – a small thing, but apparently offensive to some of her new neighbors.

She soon found herself ostracized. The residents of the Hill wanted Lizzie to disappear quietly, to relieve them of the burden of her presence. Her displays of wealth – the new house, a fine team of horses for her carriage – put off many of the same people who had supported her during the trial. At the Congregational church, where she had always been active, women she knew drew their skirts aside as she passed, and men refused to look at her. She sat alone, surrounded by empty pews. She stopped going to church.

The public that had cheered her acquittal turned against her as well. The Fall River Daily Globe, which had declared Lizzie Borden the killer two days after the murders, refused to accept the verdict. For two decades thereafter, on the anniversary of the Borden murders, the Daily Globe ran thinly veiled, sarcastic diatribes such as this one, which appeared in 1904:

“There occurred one dozen years ago today, one of the most shocking, unnatural, base, and mercenary crimes that ever befouled the pages of civilized history, and the demon that swung the axe, which sent two souls into eternity at that time, has never yet been punished for his – or her – crime:”

Lizzie was soon confined to her home by the curious crowds that would gather whenever she was seen in Fall River. Russell Lake, who grew up across the street from Maplecroft and as a boy sold lemonade to the kindly woman who lived there, recalled that the wagon drivers who met trains carrying workers from Boston used to drive by to point out the home of the infamous Lizzie Borden.

In 1897 Lizzie Borden again found her name splashed across the headlines of the region’s newspapers. A warrant for her arrest was issued in Providence for the theft of two paintings on porcelain from the TildenThurber Company. But the warrant was never served.

For the rest of her life, Lizzie went into a sort of internal exile. She changed her first name to Lizbeth. She avoided Fall River society, fed birds and squirrels in the seclusion of her backyard, and quietly engaged in charitable work. She left her house only by coach and, later, a chauffeured car and took to visiting Boston, New York, Providence, and Washington for shopping and entertainment, especially the theater.

Much was made of her friendship with actress Nance O’Neil – it was a time when acting was still considered a morally questionable career. Lizzie hosted parties for the casts of plays at Maplecroft often enough that her sister, Emma, scandalized, moved out of the house in 1905. They rarely spoke thereafter, but in the only interview she ever granted after the break, Emma defended her sister. “Queer? Yes, Lizzie is queer,” Emma said. “But as for her being guilty, I say no, and decidedly, no.”

In 1926 the newspapers discovered that a “Mary Smith Borden” who had checked into a Providence hospital with gall bladder trouble was actually Lizzie. She was reported to have been a troublesome patient. After a year of continuing health problems, she died at home in Fall River. Her estranged but loyal sister, Emma, followed her only a few days later.

Her friends held a small funeral service at Maplecroft, and she was laid to rest in the family plot in Oak Grove Cemetery. Though close friends said Lizzie had a theory about the identity of the murderer of Andrew and Abby Borden, she took it to her grave. Over the last 34 years of her life, despite numerous requests for interviews, she never said a public word about the case.

In fact, her only public utterance after the trial was her last will and testament, executed 16 months before her death. Of her estate, estimated at $265,000, she left nothing to Emma, saying, “She has enough to make her comfortable.” The city of Fall River got $500 for perpetual care of her father’s burial lot; there’s no mention of her stepmother. She was generous to her servants and left cash and jewels to a number of friends, including “an old schoolmate, Adelaide B. Whipp.”

Her largest bequest, $30,000 in cash plus some stock, went to the Fall River Animal Rescue League, explaining, “I have been fond of animals and their need is great and there are so few who care for them.”

There is almost nothing in it to suggest the circumstances of one of the strangest lives in American history, a life sundered by what happened on a hot day in August 1892. Nothing but this: She signed the document twice – once as Lizbeth A. Borden, and once as Lizzie A. Borden – as if they were two different people.

One of Lizze Bordens lawyer’s was Melvin Ohio Adams originally from Ashburnham Mass. then a Boston high profile lawyer.

Great story it’s good to know these things

The maid I feel the father and mother . I feel she was having an affair with the father she was mad so she killed them both.

I felt it was maybe an out

I felt maybe someone came from the out

-side. It’s so strange,maybe she payed someone to murder her father and step-mother. Very ????

I had A terrible dream that Lizze Bordens

Step-mothers brother w/ the help of Lizzy

Did the crime.

Wonder if it was Emma who did the murders

Maybe it was Emma and Lizzie covered for her

I saw what you did & I know who you are.

The movie starring Elizabeth Montgomery had a plausible twist: that Lizzie committed the murders while completely nude. That way, she’d have no blood on her clothing and washed herself off down in the basement of the home. Maybe it’s a stretch, but it could have happened.

I saw the Montgomery made for TV movie decades ago and have always thought that the naked murder/rinsing with a pitcher of water while standing in a shallow basin was a very plausible explanation of the no-blood-found evidence. Also, those huge Victorian dresses covered all body parts and would allow for no blood to get on the murderer, hence the burning of the “paint” dress after the funerals. There might not be direct evidence against Lizbeth,

but who else would do a no-motive axe murder, walk around town blood covered with an axe, then return 2 hours later to do the “41” ? It leaves no doubt in my mind that Lizzie was guilty. Such a sad, tragic story.

I imagine if it could be done it would have already happened. With today’s technology it would so interesting if a new look into the murders produced a definitive answer to the question of who killed the Bordens.