The Killing of Karen Wood | Yankee Classic

When a young Maine mother was shot by a deer hunter in her own backyard, the tragedy wounded the entire community.

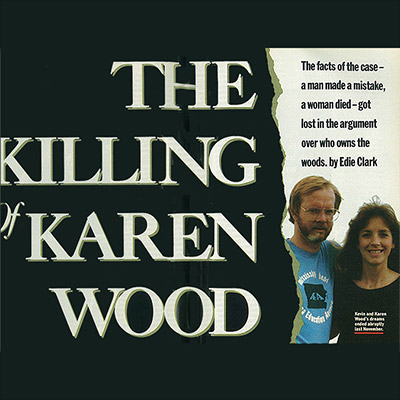

The facts of the 1988 death of Karen Wood — a man made a mistake, a woman died — got lost in the argument over who owns the woods.

On the morning of November 15, 1988, Dr. Kevin Wood had rarely felt better. He was up early, showered and changed, anxious to get to his new job. He gave Karen, his wife of 13 years, a kiss and a hug and gathered his baby twin daughters — pink-cheeked, blond-haired, blue-eyed bundles named Laura and Lindsey — into his arms, and covered them with little kisses. He left then, driving in his brown Honda Civic down the quiet road in Hermon, Maine, where they had moved only recently from Iowa. It was only ten or 15 minutes to the Eastern Maine Medical Center in Bangor where he had begun work in July. He was 36 years old, tall and lean and blond, his face edged in a red beard with a white swath down the side. He had told friends and family that this new position, working with children with psychological problems, was “the perfect job.”

That afternoon, Karen was smoothing sheets of wallpaper to the walls of her brand-new kitchen, which she had told friends back home was the “kitchen of her dreams.” Karen felt as Kevin did: coming here to Maine was the culmination of many efforts, and everything she did for this house, for the babies, for Kevin, she did with a radiant glow that even the most casual acquaintance picked up on. The paper was deep blue with tiny white flowers, a pattern she had spent a great deal of time selecting. Laura and Lindsey had only just taken their first steps, so progress was slow as she watched them move about unsteadily and measured for the next piece of wallpaper.

No one can say why, but some time after 3:00 P.M., she laid down her tools and put the babies behind the child gates in the living room. Outside, bright sun shone through bare trees, but the air was Halloween-crisp, so she put on her dark blue jacket and pulled on a pair of white mittens before stepping out the glass door to the deck that overlooked their acre and a half of scrubby woods. She went down the steps and through the fenced-in dog kennel that extended 100 feet beyond the deck. She opened the gate and stepped out.

In the clearing, some 63 yards from Karen, Donald Rogerson, a hunter well known in Bangor sporting circles, raised the barrel of his 30.06, a very high-powered deer rifle with a four-power sight, took aim, and fired. He lowered the gun, pumped another round into the chamber, and once again pulled the trigger.

Across the street, Cheryl Hamlin was sitting in her living room. She heard the shots, too close, way too close. Then she heard cries and a voice: “Help me, help me, dear God, please help me!” She grabbed the phone and dialed the sheriff. As she spoke, she watched out the window. A man in blaze orange pounded on the Woods’ front door where inside the babies’ cries swelled out.

Toward the end of the day, Kevin was called to the emergency room to see a young girl who had threatened suicide. He spent some time with her and decided, somewhat reluctantly, not to admit her. He spoke gently to her and then returned to his office where there was a call waiting for him from the emergency room. His first thought was that something had happened to the girl he had just left. Instead it was a man from the sheriff’s department who told him that there had been a hunting accident and that his son had been shot. Kevin doesn’t have a son, so he told the man there was some mistake, but the man insisted that Kevin come home. He did.

Listening to his car radio on the way, he heard a news report of a hunter who had been shot in Hermon. He felt confused, and yet when he turned down his road, seeing the crowd of police cars, TV trucks, news reporters, and game wardens, and the yellow police tape drawn around his property still did not convey to him what had happened: Karen was dead. Her body, pierced through the chest by one of Rogerson’s bullets, lay in the backyard, covered by the brown and beige blanket of a neighbor.

During the next hours, as the brilliant afternoon turned to night, events swirled around Kevin with nightmarish unreality. Within an hour or so Donald Rogerson was arrested for manslaughter and taken to the Bangor jail. Because her death was related to hunting, game wardens rather than police handled the investigation, and young uniformed wardens, it seemed like an entire squadron of them, swarmed through Kevin’s backyard. They worked intensely around the crime scene, some of them down on their hands and knees, scouring the leaf-covered earth. When darkness closed in, they switched on flashlights and continued. It was 7:00 P.M. before the medical examiner could get there from Augusta, even later before the hearse came to take Karen’s body away.

Inside the house, neighbors and rescue workers tried to comfort the babies, who cried and cried for their mother. Night turned to day. Kevin did not sleep and neither, it seemed, did the wardens. Kevin turned away reporters. He could not talk, he could not imagine talking.

The next day Kevin, in numb disbelief, carried out the sorrowful task of following Karen’s body home to Binghamton, New York, where they had been born six months apart, where they went to high school together, where they fell in love, where they married. Before Kevin left, Gary Sargent, the warden in charge of the investigation, assured him that all this, gathering of evidence was being done in preparation for the trial, which would surely follow this ungodly event. Over the next several days, the wardens took extensive measurements, photographs, videotapes, and even pictures from the air. They cut down the tree Karen had stood beside when she was shot and took away the trunk in which was lodged the other bullet.

Three weeks after the shooting, Kevin returned to Bangor from Binghamton where he had stayed with his parents following the funeral. He left the twins in the care of their four doting grandparents until he felt settled enough to bring them back to the house at Treadwell Acres. While he’d been gone, he had read none of the newspapers, which had throbbed almost daily with the news and opinions about Karen’s death. Because the investigation was still underway, few facts about the shooting could be released. In the write-ups there were few details about Kevin or Karen, nothing about the funeral, and only a brief obituary for Karen. The focus was on the hunter.

More than one front-page story featured tearful apologies from Rogerson, who, it was headlined, was a scoutmaster in Bangor. “A most wonderful kind of person,” one of the Woods’ neighbors was quoted as saying. One report opened by setting the scene at the supermarket where Rogerson is the produce manager. It described customers lining up to shake the hunter’s hand and make offers of prayers and support, as if he were somehow the victim. While Kevin had been silent, Donald Rogerson had talked, and graphic details of his experience emerged. “I almost fainted when I came up on her,” he told one reporter. “I…messed my pants.”

What didn’t emerge were the details that mattered: what he was shooting at, how long he’d been in the woods, how many shots he fired, whether or not there were deer seen nearby. One warden excited much comment by saying Rogerson may have mistaken her white mittens for the tail of a deer, overlooking the fact that Rogerson was hunting for buck and needed to identify the head, not the tail, of the deer before shooting. What Rogerson did say, over and over, was how sorry he was, to almost anyone who would listen. He didn’t know he was so close to houses; he thought he was shooting at a deer, he said.

In letters and guest editorials to the Bangor Daily News, though many sympathized with Karen, some readers took issue with the fact that she was wearing white mittens, and why wasn’t she wearing blaze orange, as anyone who lives in Maine knows well enough to do during hunting season?

It was as if they were saying that Karen was to blame for her death. And there were overtones of provincialism — she was from away and didn’t know enough to keep herself out of trouble. One guest column by Theodore Leavitt began by saying that Karen’s death illustrated several important issues, “the most important of which are the development of what were traditionally wilderness areas and the influx of large numbers of people who do not share or understand the traditional views and values of native Mainers.” He went on to question Karen’s “common sense, going into the woods dressed as she was.” The facts of the case — a man had made a mistake, a woman had died in her own backyard — became obscured. What took over was a fiery debate between hunters and non-hunters, all the old arguments over who owns the woods.

Unaware of all this, on Monday, December 5, Kevin returned to work, feeling he could slowly ease back into the job. He had seen one client in the morning and was about to settle in with an afternoon patient when a call came through from Maine’s Assistant Attorney General, Jeffrey Hjelm. Unknown to Kevin, that morning Hjelm had brought the evidence gathered by the wardens before a grand jury.

It was the task of the grand jury to determine, on the basis of that evidence, not whether Rogerson was guilty of the crime of manslaughter, but merely whether there was sufficient cause to suspect that the crime may have been committed. Manslaughter is defined as causing death through conduct that is either criminally reckless or criminally negligent — to fail to be aware of a risk or to disregard the risk that your conduct could cause death. Under Maine law the proceedings of the grand jury are secret and the identity even the numbers — of members of the grand jury are concealed, so what was presented in that session may never be known. Whatever it was, the grand jury decided not to indict Donald Rogerson for manslaughter in the shooting death of Karen Wood.

This is what Hjelm had to say to Kevin that afternoon. Stunned, Kevin got up and walked out of the office, without a word, and drove home to Binghamton, where he remained, paralyzed with grief, for seven long months.

It was not the first time that Kevin had suffered loss. The way he describes growing up in his family of four children is, “I was the one who dodged the bullets.” His older sister was mentally retarded, and his younger sister died at age 14 of cystic fibrosis, a slow, painful death that monopolized the family during his adolescence. His younger brother died of leukemia in 1987. He feels there is little question that these experiences led to his interest in psychology and his work with children. And it was definitely a factor in his and Karen’s decision to delay having children. The twins, conceived following his brother’s funeral, underwent prenatal testing for retardation as well as tests in their early infancy for cystic fibrosis.

In fact, few lives had been charted so carefully and consciously to avoid mistakes, to maximize the best options. After they were first married, they lived awhile in New York and then in Virginia. In 1978 they moved to Iowa where Kevin planned to complete his doctorate at the University of Iowa and Karen hoped to get her degree in business. They worked while they studied — Karen as a loan officer at a bank and Kevin at a local hospital — and so it took them ten years to do it, but when they completed their objectives, it was sweetened by the birth of Laura and Lindsey.

In fact, Kevin views 1987 as a kind of watershed in their lives. “Nineteen-eighty-seven was a bittersweet year,” he says. “Mike died in February. We found out there were twins in early May. I graduated in late May, and the babies were born in October. It was a crazy year. “

A crazy year that signaled the need for another conscious change in their lives. Laura and Lindsey were the first grandchildren for both their sets of parents, and the need was clear to leave Iowa and get back to the East Coast, closer to the grandparents. Kevin’s work was specialized and so he focused his job search throughout the Northeast. “I couldn’t have written a better job description,” Kevin says now of his job at Eastern Maine Medical Center.

They had not been so lucky in looking for a house once they moved to Bangor. They were disappointed to find the housing market in Maine much pricier than that in Iowa. Unwilling to settle for just any place, they rented a place in town and devoted themselves to the house hunt. For six weeks, they went looking at night and on weekends, walking through endless possibilities in and out of Bangor.

In August they found it, a dormered Cape in a new development called Treadwell Acres in Hermon, a small town on Bangor’s periphery. They loved the country setting — this was the last house on the road so there would be virtually no traffic to worry about with the girls, and the house itself was everything they were looking for. Out back was a yard big enough to make a kennel for Maxie, Kevin’s hunting dog. The only drawback was that it was still above their budget. It was only through Karen’s background as a loan officer that they were able to push through to a mortgage they could handle.

On Labor Day Kevin and Karen moved their furniture and their twins into their new home in a kind of triumph. “We were convinced that this was where we were going to live for a long, long time,” Kevin says.

Though they had been in the area only a few months, they had begun to make friends, most especially with Tim and Maggie Rogers. They went to dinner often, and Kevin joined Tim’s Thursday night poker group. Kevin and Tim planned to hunt together in the fall, and they talked of camping trips. Tim was Kevin’s boss, and Tim was one of the first persons Kevin called when he arrived home to that grim scene on that November afternoon.

The day following the shooting, Tim stayed and watched the wardens mark the spots — where Karen lay when she died, where Rogerson stood when he took aim and fired — and measure the distances. He watched them and remembered, for that has been their only access to the facts that surround Karen’s death, a situation that remains one of the most troublesome aspects of this painful experience. The rest he and Kevin have pieced together for themselves.

They have stood on the spots where the hunter stood and where Karen lay, time and again, and seen his line of fire, which they say was a clear shot across an opening recently logged. They have gone back out there at that same time of day and seen that the sun was at Rogerson’s back, that it shone brightly off the white house next door, and off the chain-link dog fence so near to Karen.

Perhaps worst of all, they know that Rogerson’s truck was parked only a short distance from the Woods’ house, so that for him to say that he didn’t know he was near any houses shows that he was disoriented. Kevin and Tim believe he was less than 300 feet, the legal limit, from the neighbor’s house. They believe he was hunting illegally.

A curtain of silence surrounds this case. The wardens won’t talk, the hunter won’t talk, and in accordance with state law, the attorney general won’t talk. They will not release the photographs they took. They will not say if any tests for drugs or alcohol were done on Rogerson. They will not say if there was any evidence of deer found nearby. They will not confirm the kind of gun Rogerson was using. They will not say whether or not Rogerson was hunting legally. They will not say what Karen was wearing when she died.

Until recently, Hjelm wouldn’t even confirm that the grand jury met and refused to return an indictment. Because the case is still open, there is still a possibility of a trial and release of any information may jeopardize a fair trial.

“It’s frustrating,” Hjelm says of his need to remain tight-lipped. “It’s very frustrating, but we can’t be shortsighted about it.” It is even more frustrating for Kevin, who was denied access to any of the evidence compiled by the wardens when he brought a wrongful death suit against Rogerson.

In fact, so few details were released following the investigation that Kevin forced himself to read the autopsy, a gruesome description of the violent extent of her injuries. The autopsy was one of the few things he was allowed to see. “I hated the fact that other people knew something about Karen that I didn’t,” he says.

Everyone knows who killed Karen Wood. That has never been a question. The question seems to be whose fault was it that she died. The fact that Rogerson was released and suffered no legal penalty for her death, not even the revocation of his hunting license, seems to reinforce the idea that somehow Karen was at fault. Kevin can’t abide that and neither can Tim.

“It feels totally unfinished to me, totally unfinished,” Tim Rogers said recently. “I think anyone who takes a high-powered rifle and points it and pulls a trigger and kills somebody has committed a crime.”

In February Tim was a panelist on a TV talk show to represent Kevin’s point of view about Karen’s death, a controversy that even then remained hot coffee-shop conversation. He was stung by the tone of many of those who called in, one referring to Karen’s “stupidity” in “presenting herself as a target.” Tim is from Georgia and has lived in Bangor only a few years, but he likes it and wants to stay. The attitudes that emerged during this charged-up time gave him pause. He rejects the notion that some of this might have been Karen’s fault because she didn’t know how Maine worked. “I don’t want to believe that because that means I don’t get the same protection under the law that Mainers get. I want to believe that my rights would be as well respected as the natives’.”

The idea that Karen may have been somehow to blame for her own death brings out the psychologist in him. He sees it as a classic case of blaming the victim. “No one wants to believe that a thing like that can happen to a woman who has everything going her way. I mean, if something like that can happen to someone with that much on the ball, what about the rest of us? It means that anything can happen. So we want her to be responsible so we can feel safe.”

Since Karen’s shooting, a bill was brought before the state legislature to increase the legal hunting distance from a dwelling to 200 yards. It died in committee. The Bangor city council enlarged the zone in which no firearm may be discharged except for protection of livestock. The neighboring town of Hampden passed an ordinance limiting the discharge of firearms within the town. The town of Hermon, as of August, was discussing such an ordinance.

And far from Maine Karen’s death made a difference. A close friend of Karen’s who lives in Clark County, Washington, made a tearful proposal, based on Karen’s death, for that county to increase the hunting distance from residences. The ordinance passed.

In the months following the shooting Kevin returned to Bangor only a few times, briefly, to check on the house, which was left frozen in time from that November afternoon, the wallpaper still only half hung in the kitchen.

He engaged a lawyer who brought suit against Rogerson for wrongful death, and in late May a settlement was reached: $122,000 went to Kevin and the babies from Donald Rogerson, much of the money coming from a liability clause in Rogerson’s homeowner’s insurance. Kevin called the settlement a “pittance,” but claims he needed to be realistic about it. “No amount of money could bring Karen back. The man has a limited net worth. You can’t get blood out of a stone.”

He also made the decision to move back to Iowa, where he and Karen had close friends. “I certainly had plenty of time to evaluate what living in Bangor would be like. I just decided there was no way, as difficult as it was to leave. Bangor represents the city of our dreams — the perfect house, the perfect job, the ideal family. Just too many dreams gone by. The dreams died with Karen.”

At Doug’s Shop ‘N’ Save in Bangor Donald Rogerson still stocks the shelves with apples and pears and celery and makes sure the items at the salad bar are fresh and varied. He lives nearby with his wife and children in a white clapboard duplex on a small lot with hardly any yard at all. He is 45 and has lived all of his life in Bangor. He has hunted since he was 10 loves to hunt, but since the shooting he has said that he will “never hunt again” though there is nothing to stop him should he have a turn of heart.

He is soft-spoken with reddish hair and deep-set blue eyes that bear out the words that appeared in the papers following the shooting: nice guy, good citizen. Except for the hubbub that followed the shooting, his life has changed little, if at all. He is surprised when approached by a reporter, seven months after the shooting. “I know of murders that die quicker than this,” he says, unable to understand why Karen’s death is still newsworthy. He wants to talk, seems almost to need to talk, but on the advice of his lawyer he declines the request for an interview and turns back to his work.

Kevin Wood has never seen Donald Rogerson face to face. He doesn’t want to but he sees him in his mind’s eye. Kevin has moved into a new house in a quiet suburban neighborhood in Davenport Iowa. Like the house on Treadwell Acres’ there is a bow window in front and a deck out back. Otherwise, it is far from the house of his dreams. He has hired a nanny to take care of Laura and Lindsey, a pretty girl named Kim who makes the girls laugh by blowing air onto their stomachs and who feeds them grilled cheese and cut-up pieces of fruit as their mother might have. Kevin has a new job, a good job but nothing like the one in Maine. He is happy to be back, though, because there are good friends nearby who remember the wonder of Karen. And he is happy to be away from the noise, the harangue that surrounded Karen’s death.

On his desk is a letter from Jeffrey Hjelm, reassuring Kevin that the case is still open and will remain so for five years. If any new evidence emerges, there could still be an indictment. Kevin holds hopes that there may someday be a trial. It angers him that Rogerson can still go into the woods with a loaded gun. It angers him that Rogerson knows things about how Karen died that he doesn’t.

The house is filled with push toys and fuzzy pink bears, and on weekends, when Kim is not there, Kevin finds himself on the couch, watching cartoons while the babies spin about the living room. To someone who has never met Karen, the girls have their father’s eyes and his hair, seem to look just like him, but to Kevin they look like Karen. Though they cry, maybe too hard, when there is knocking at the door, Kevin doesn’t feel that the girls endured any real trauma from the day that Karen died, only that they will have to live the rest of their lives without their mother.

And he worries about what he will tell them, how he will explain that the man who shot their mother was never brought to trial. His life, he says, was in pieces, and now is the time, at last, to start living again, to move on past the tragedy they left behind in Bangor. In the meantime, Laura and Lindsey have bonded with Kim and love to give their daddy lots of kisses. When he comes home from work at the end of the day, they squeal and propel themselves toward him on sturdy little legs, two whirling pinwheels of life.

“The Killing of Karen Wood,” was first published in Yankee in November, 1989 and has been updated for NewEngland.com