Remembering the Blizzard of 1888 | Yankee Classic

The Blizzard of 1888 dumped the greatest amount of snow ever to have fallen in the United States in one storm. And author Judd Caplovich discovered more about it than anyone who lived through it.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanJudd Caplovich lives in a house whose shrubs were once shorn by a tornado, a house that has been struck by lightning—twice. Storms come to him. He was six years old when another tornado struck Worcester, his hometown, in 1953. As it tore its lethal trench just three miles away, the boy wandered outside, arms outstretched, palms upward, to catch the hailstones. A few years later, when Hurricane Donna swept into Massachusetts, he was out on his paper route, hurrying to deliver the last of the papers. The wind howled around him. As he crossed the street, an electrical transformer exploded above his head. He ran home, those last papers still in his bag. In 1973, in an ice storm that left even the major highways of Connecticut hopelessly greased, he and 12 other members of his car pool, stranded by the storm, huddled in a tiny Hartford apartment, the only place that still had electricity. Judd slept on the floor of the kitchen that night.

One of the first things Judd collected was the headlines of the storms. He saved the Worcester Telegram and Gazette that chronicled the 1953 tornado and then there were the hurricanes in 1954 and 1955, and the accounts of the floods of the same year that virtually destroyed Winsted, Connecticut. Later he found headline editions from the Hurricane of ‘38, a storm so fierce that his grandmother recalled for him that she had seen trees flying through the air. Before long he had two boxes full of these newspapers, chronicling the aftermaths of disasters. But he had nothing on the Great Blizzard of 1888, the greatest snowstorm of all times. And that kind of got him thinking. “I knew where there was a large collection of photographs of the storm, and I knew there wasn’t very much written about it. So I decided to do a book. To fill the void,” he said.

Photo Credit : Erick Ingraham/Yankee Archives

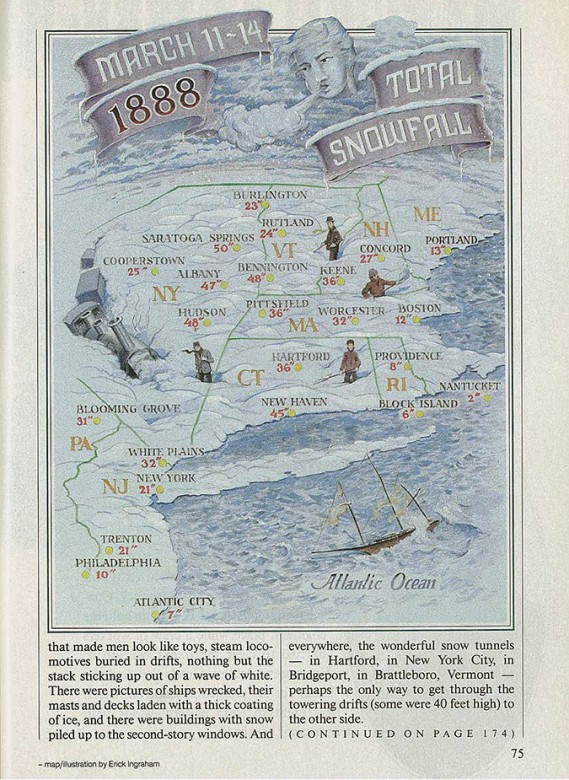

Blizzard! The Great Storm of ‘88!, a hefty three-pounder loaded with pictures of the blizzard of 1888, that surprise mid-March storm that buried ten states in three, four, and five feet of snow, that drifted up to 40 feet, just as crocuses had come into bloom and farmers had begun their spring plowing.

There was precious little meteorological data available on the blizzard, which is now commonly believed to have been a collision of two massive storm fronts. He called Paul Cozin, a NASA research meteorologist up, and they talked, and before long, Cozin was at work with Judd, mapping out the path and progress of the entire storm, something that had never been done before. Similarly, Judd contacted David Ludlum, who has written more than ten books about weather and its phenomena, and he joined in.

He found first-person accounts of the blizzard in some of the newspapers he’d run through on microfilm. In the New York Times, he found this account by a woman watching the storm from her apartment window: “I saw a man for one and a half hours trying to cross 96th Street. We watched him start, get quarter way across, and then be flung back against the building on the comer. The last time he tried it, he was caught up in a whirl of snow and disappeared from our view. The next morning seven horses, policemen, and his brother charged the drift, and his body was kicked out of the drift.” The newspapers abounded with grim stories—the account of a farmer finding a woman frozen to death in his outhouse, where she had sought shelter, having lost her way in the ferocious storm. And the two children in Waterford, Connecticut, who were making their way to their aunt’s house and were quickly buried in the fast-falling snow. They huddled together for hours inside the snow cave until searchers found them by poking through the snow with a stick. They were alive, their hands and ears frostbitten. The icy snow whipped by gale-force winds made being out in the storm like being in a sand storm or being sandblasted. It was reported, here and there, that people had resorted to wearing squares of carpeting on their feet and blankets around their heads, or bags with holes cut for eyes.

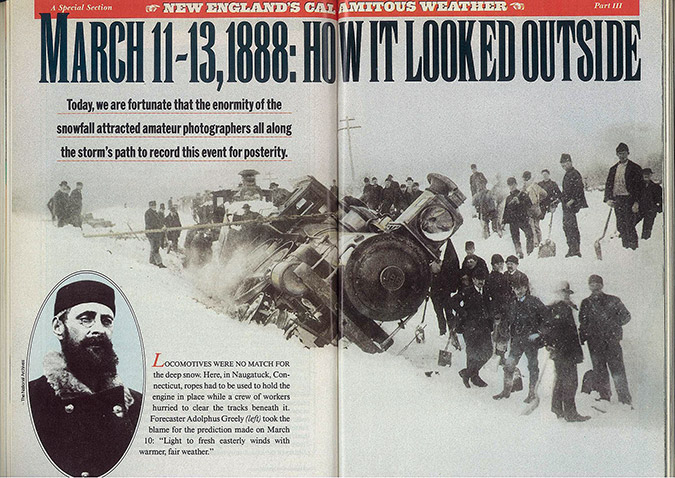

For three astonishing days in 1888—March 11 to 14— a whirlwind of ice and snow pummeled the region, and when it was over, it had taken the lives of 400 people and caused uncalculated damage. In New York City, where such things were capable of being totted up, there was an estimated $20 million worth of damage. It was the greatest amount of snow ever to have fallen since the formation of the United States. Nothing since has overtaken that record.

In his reading, Judd found that the entire Northeast had been paralyzed by the blizzard. Telephone and telegraph wires were down from Washington, D.C., to Maine, and the trains, which provided the only real transportation in those days, were at a standstill—many smashed to ruin, some stuck in drifts, some never able to leave the station. In Bridgeport, Connecticut, more than 1,000 passengers crowded into the station, unable to go home, unable to go anywhere. Among them was a traveling theater group, who had come to perform “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” at a Bridgeport theater that week. They did an impromptu performance for the shivering crowd, then and there. Passengers on trains that had become stranded for days in a virtual snow wilderness fared better or worse, depending on what the baggage cars held. One trainload of starving passengers discovered five gallons of oysters and 300 pounds of bacon and sausage when they looted the stock. Another happy group uncovered a load of tenderloins which they fried up on the coal shovels over the passenger heaters. Melted snow provided further refreshment. But the luck on another train, hung up in a drift in Brookfield, Connecticut, was not quite so sweet. There, a brave stationmaster forged his way through the raging storm, loaded down with all the eggs and bread he could handle, plus a gallon of brandy. This sorted out to one egg and two slices of bread for each famished passenger to keep them going another 24 hours until help arrived.

Photo Credit : Yankee Archives

There were recollections chronicled by a group called the Blizzard Men of ‘88. All of them had lived through the storm, and they got together for years afterward to share their memories. Here is one that Judd found: “By night the drift had reached the second-story windowsill. When we were ready to depart at 6 o’clock, we found a solid wall of snow as the lower door was opened . . . We did have two shovels. It was necessary to tunnel through for about 15 feet, carrying snow upstairs and throwing it out the back windows. Making an exit … our combined strength weathered the gale in an almost exhausted condition.” The accounts were numerous and tragic as well as comic, such as the story of searchers coming across a body, hard as rock, in a high drift of snow. After frantic efforts to uncover the “corpse,” it turned out to be a cigar-store Indian. And the one of the woman in Hartford, who had taken a dozen strangers, trapped by the storm, into her home. Food ran out quickly but under her back porch she discovered another group of refugees—a flock of perhaps a hundred sparrows. She gathered them up and served the hungry strangers sparrow pie.

Working at a frantic pace, 16 hours a day, seven days a week for almost a year, Judd collected these tales and wove them into a text that went along with the more than 300 illustrations he chose for the book. It was not always easy—he remembers spending one entire day in Concord, New Hampshire, sorting through mountains of pictures and finding not a single one of the Blizzard of ’88.

And he worked hard to find someone who had lived through the storm. He thought it was possible—the person would have to be about 106, with a clear memory, but he figured there are such people so he put ads in some of the newspapers. He got no response. The closest he came was a woman in Hopkinton, New Hampshire, who is known as the Blizzard Lady, reputedly because she was born on the day of the blizzard. She would not, of course, remember the storm, but it was the closest he had come, so he and Wayne drove up to Hopkinton and spent the day with the Blizzard Lady whom he found to be very sharp. Wayne took a lot of pictures. “She’s a hundred years old, still drives her own car, owns her own home, and has her own garden,” Judd says. “We had a wonderful day with her, but it turned out she was born on March 31. Everyone in town thought she was born on the day of the blizzard, but that would have been March 12. She did know when her birthday was, but there was another blizzard on the 31st. So I couldn’t use it in the book. That was a big disappointment because I was going to dedicate the book to her.”

At a certain point he had to stop and turn to the business of producing the book. He found a printer in Michigan. Of course, there are printers closer, but this was the one he liked the best and that involved a lot of travel and phone calls and in the end, the book came out late, a little over two weeks before Christmas, which was a disappointment because he more or less missed the pre-Christmas sales. The books were delivered to his house, where he handles all the mail orders. Five thousand books on skids arrived one morning in a tractor trailer from Michigan. There was a total weight of 15,000 pounds to be unloaded.

He was afraid the foundation would crack if they unloaded the works all in one place, so he spread it around—2,000 pounds here, 2,000 pounds there, 6,000 pounds in the basement, next to his roomful of old phonograph records.

But orders started to come in, and the burden began to lift. The book was given a prize and was given out as a prize, and on the weekend of the anniversary of the Great Blizzard of 1988, March 11, 12, and 13, Judd found himself involved in a blitz of radio and TV interviews, which was something of a surprise to him. He spent the weekend in New York City where Maria Shriver interviewed him and so did the folks at “Good Morning America.” When the weekend ended, when the centennial of the storm had crested and waned, he went home and slept, for days it seemed.

After that the orders continued to come in, slow but sure. He did not, as he had hoped, make a bundle. He has been thinking lately of other projects that might be more lucrative. He thought about capitalizing on the fluctuating foreign exchange rates by importing things from Europe. He looked into importing chocolate and traveled to Switzerland to arrange to buy a bulk load of chocolate. “But they wanted me to buy 100,000 pounds of it at a time, and I realized that chocolate, if you don’t get rid of it real quick, spoils. So that was out.” A couple of other things didn’t pan out. He keeps going back to the storms. When last we talked, he was getting together all his material collected over the years on the Hurricane of 1938. September is the 50th anniversary of that storm. He thinks there might be something in that.

Excerpt from “He’s Still Buried in the Blizzard of ’88,” Yankee Magazine, September 1988

Th Blizzard was before my time…but being from the middle of the Adirondack Mts. It must have been devastating there. Thanks for a great article.

Thank you for the great article on Judd and his research. While attending the International Symposium of Telephony at Boston College with my aunt Eleanor Macdonald, We traveled to Judd’s home and I bought 6 or 7 books autographed by him. He was a very interesting man and live in a very interesting home.

My aunt was a keynote speaker at the Symposium to present a program about my Grandfather, Angus Macdonald who was one of the “Long-Lines” linesmen who kept the telegraph lines operating in Connecticut and who later was the model used to create” the Spirit of Service” Painting which was placed in the 2 story entry of the headquarters of the A.T.&T. company in NYC.

I have the original B&W studio photographs and quite a few products which featured the painting. I was surprised when I read the book he did so much research on not to find a reference to the “Long Lines” heros.

Best regards, Ronald W. Macdonald

“The Children’s Blizzard” is a very hard book to read since it’s about the experiences of families and children when this storm hit the Great Plains in late winter. A difficult book to read but interesting for historical, first-person value.

My grandmother, Myrtle Ellis Robertson, who lived in Sullivan, NH told me of her memory of the blizzard of “88