Lessons from the Scrap Pile | Life in the Kingdom

Compression wood inspires a meditation on the gifts of resilience and being OK with imperfection.

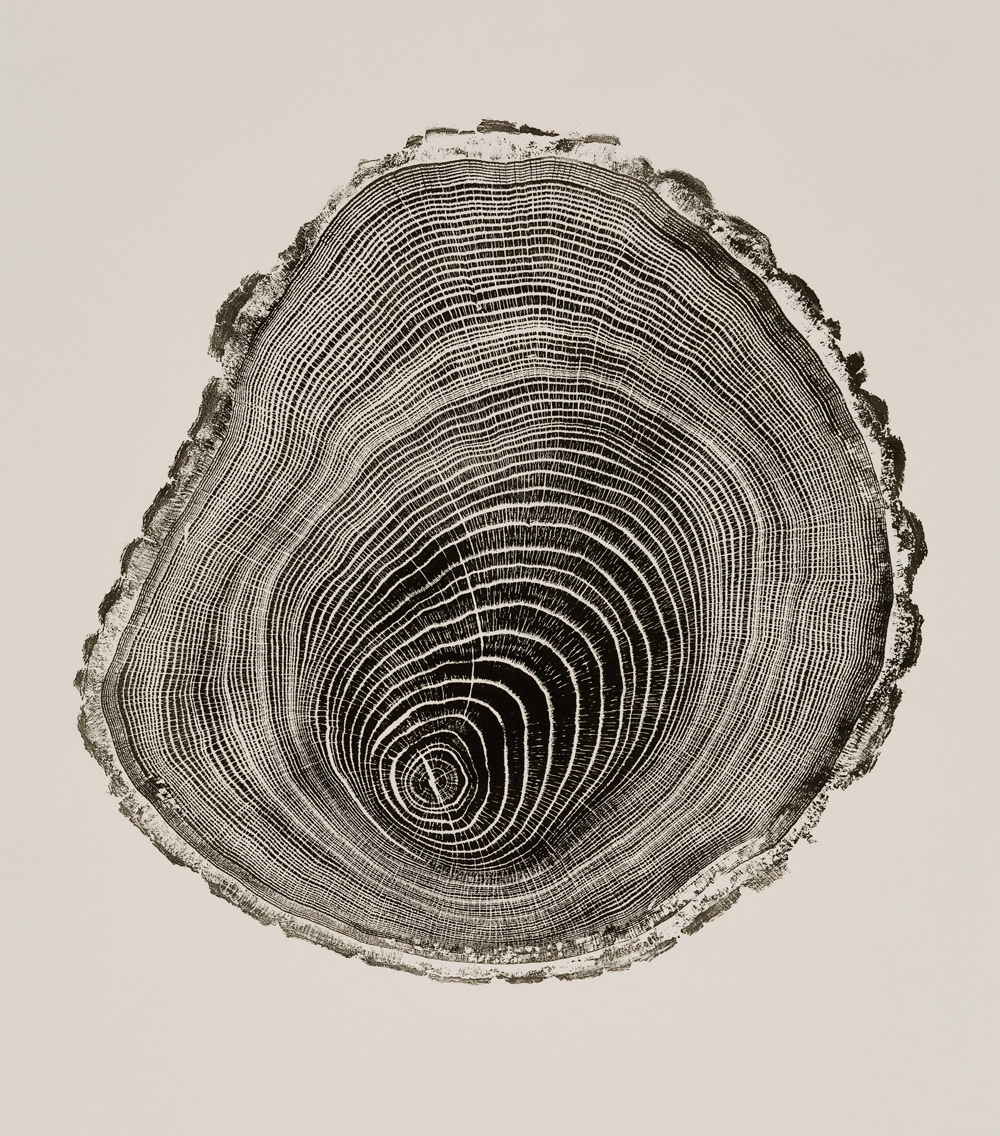

Compression Wood, 2011, a relief print made from a cross-cut trunk by the late Connecticut artist Bryan Nash Gill.

Photo Credit : 2011 Compression Wood copyright Bryan Nash Gill, www.bryannashgill.com.

Photo Credit : 2011 Compression Wood copyright Bryan Nash Gill, www.bryannashgill.com.

My friend Ross is a bit older than me, which is a nice way of saying that I’m pretty sure he’s on the wrong side of 70, though he makes the wrong side of 70 look as if it might not be the absolute worst thing in the world. Ross is a semi-retired forester, a man who knows the woods as only a person who’s spent better than half a century in the woods can know them. He’ll tell you the difference between a black ash and a white ash from 50 paces, or where to find a basswood tree. He talks about trees the way most of us talk about old friends, as if living wood were a sentient being. Which, for all I know, it is.

I’ve seen a lot of Ross lately because he and I have both been teaching at Sterling College, a small school (student body: 135) in the village of Craftsbury Common, about 15 miles west of my home. I’d wager that Craftsbury Common is one of the most picturesque villages in Vermont: It’s all white clapboard and green shutters, a few-dozen-strong cluster of old farmhouses in good repair. Many of these structures belong to the college, which makes up a goodly portion of the town. There’s an expansive green in the center of town, a well-appointed library, and a small public school serving elementary through high school students. Because of the college, which is oriented around environmental stewardship and sustainable agriculture, it’s not uncommon to see a yoked team of oxen sauntering down Main Street. Indeed, I once witnessed a team of oxen being passed by a student shuttling between classes on his skateboard. This pleased me no end.

Working at Sterling was my first formal teaching experience, and I loved it. I didn’t know I’d love it or even if I’d like it, or what to expect at all, but I figured I could gut out the semester no matter what. Ross would see me on campus, usually in the dining hall, and he’d ask me how it was going, and when I told him how much I enjoyed my class and especially my students, he’d smile his big smile and say, “Oh, good.” Then he’d say, “I’ve gotta get you a copy of ‘Compression Wood.’” He’d been after me to read that Franklin Burroughs essay all semester, though he never really said why. But I could tell from the way he smiled that he loved the essay, and that he was pretty sure it’d speak to me, too.

Ross finally delivered “Compression Wood” to my school mailbox. It’s a long piece, nearly 20 pages, and the first time I read it, I read it slowly, over a period of days. The essay centers on Burroughs’s friend Rod McIver, who has schooled him on the qualities of compression wood, which develops in a leaning tree as a response to the force of gravity. Compression wood, as McIver explains, is not useful wood; when sawed into lumber, it always wants to twist and warp and bend. It’s of little economic value. McIver sorts it into the scrap pile but figures it might not be worth even that. “I waste nothing,” McIver tells Burroughs. “Except my time.”

To Burroughs, of course, compression wood is something more than low-grade lumber. It is a metaphor for that which does not fit in, for that which is imbued with strength and character but, for reasons beyond its control, lacks sufficient market value. Perhaps, Burroughs muses in his essay, the character of compression wood, the way it forms in response to a particular set of circumstances in a particular tree, and the very lack of extrinsic value, was actually proof of another type of value altogether. Call it artistic, or intangible. Or think of it in relation to the living tree, for which compression wood is plenty valuable; it enables the tree to survive, after all. Or maybe don’t call it anything or think of it at all. Maybe just appreciate it for what it is. Something unique. Resilient. Maybe even a little defiant.

My Friday class met in the mornings; by the time I returned home, it’d be 12:30 or 1 p.m., and I’d warm up the tractor while I changed clothes, then ride into the woods, the tires churning through the deep snow. The urge to be in the woods—and not just in the woods, but working in the woods—was particularly strong on the days I taught. This was a response, I suspect, to the relatively sedate and cerebral nature of the classroom. It was also a response to the fact that the next winter’s firewood wasn’t going to cut itself.

So to the woods I went, and there I experienced, as always, the bone-deep satisfaction of labor, the sensation of my muscles strengthening in response to stress, like the fibers of a leaning tree. And, concurrently, the less physical but no less tangible satisfaction of maintaining a connection to the raw ingredients of my family’s well-being. “People who don’t work with primary resources don’t understand reality,” says McIver in “Compression Wood.” Maybe he’s right; maybe he’s not. But I understand what he means. It does feel a little crazy to be so disconnected from the fundamentals.

Next time I bump into Ross, I’m going to tell him how much I liked “Compression Wood,” how it spoke to so many aspects of my life, and in so many ways. And I’ll tell him that my favorite lines are these:

You cannot ask yourself what you are doing here, or why you are doing it, because those questions lack answers that would fit anybody’s definition of sanity. You can only keep doing it, doggedly, deliberately, scrupulously, as though in obedience to something, or in honor of it.

As though in obedience to something, or in honor of it. I think of Ross, and his relationship to the forest, and the way he makes it seem as if a tree is never just a tree, but an actual being. I think of my own work in the woods, every step of it in defiance of economic sensibility. For if I allocated even a modest wage to my time, and calculated the true cost of operating saw and tractor, surely I could purchase firewood far cheaper than I can cut it. I think of the chores that bookend our days, and how from the outside they must seem burdensome, and even boring, always the same routine of water and feed and fencing. Our last family vacation was in 2007. That’s not a lament, just a statement of fact.

Finally, I think of being in class, and telling my students one of the hardest truths about writing: that most of what anyone writes—and I’m talking about even good writers, the very best, probably even Franklin Burroughs—isn’t worth much. It belongs in the low-grade pile, right there with McIver’s compression wood. Just forget about that stuff, I said. Besides,you gotta get through the bad to get to the good. It’s part of the process. You’re not wasting anything.

And here I paused before finishing, already pleased with myself: Well, except your time.

Ben Hewitt

The Hewitt family runs Lazy Mill Living Arts, a school for practical skills of land and hand. Ben's most recent book is The Nourishing Homestead, published by Chelsea Green.

More by Ben Hewitt