Keeping Time

By rescuing hundreds of thousands of old newspaper images, a Portland archivist has given his city a priceless family album.

The author at home. In addition to his full-time job as an archivist, he writes essays and studies and teaches philosophy, “believing that each person’s observations are eminently worth recording.”

Photo Credit : ©Abraham A. SchechterBy Abraham A. Schechter

Photo Credit : ©Abraham A. Schechter

In late 2009, I seized upon an unusual opportunity that few archivists ever encounter. Maddy Corson, the granddaughter of the Portland Press Herald’s founder, alerted me that the newspaper had again been sold and that the building constructed by her grandfather in 1923 was being gutted. For me, as the Portland Public Library’s archivist, preservation and access to history are of primary importance.

Hurrying downtown by bicycle, I saw large piles, stacked boxes, and bags of unorganized photographic negatives in the Gannett Building’s basement. Being a lifelong photographer, I recognized the mounds of cellulose fragments as camera originals, surely holding a century of regional history.

Photo Credit : ©Abraham A. Schechter

Finding the demolition supervisor, I asked him about the film. He was surprised that I wanted the discarded negatives, even after I told him what they meant. “You want this stuff? Then you gotta take it away this week, or it’s all going to a smelter,” he said, referring to the film’s silver content.

“That’s not going to happen,” I said. “I’ll take it all.”

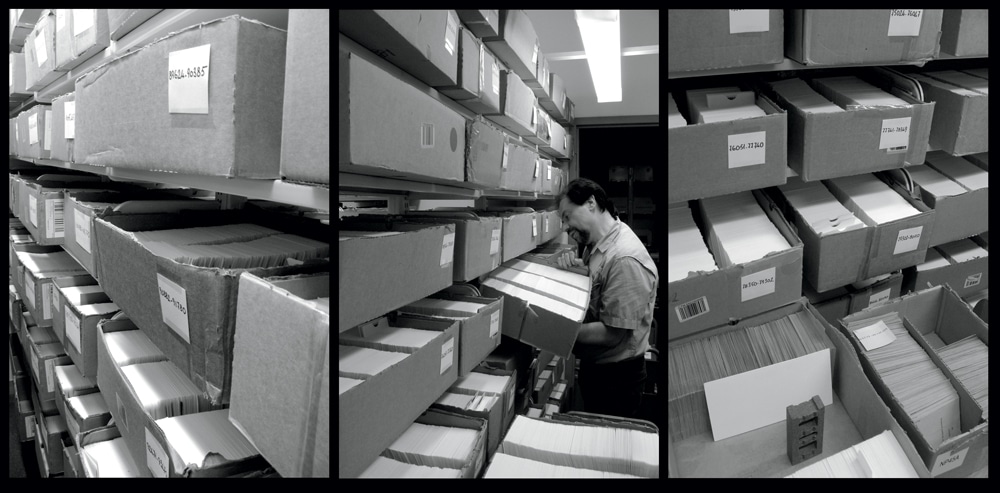

With Maddy’s support, along with the library’s, the film was moved out of the damp basement to a workspace for me to begin the herculean task of salvaging and rescuing what has turned out to be a priceless trove of more than half a million unique photo images, taken between 1936 and 2004.

It took three years to analyze, organize, and arrange all the film; during that first pass, I examined more than a million exposures. Afterward, I began rehousing the images, now protected in alkaline enclosures, at the library. The processes are painstaking, requiring precise locations, names of buildings and people, and dates so that these images—which had been right on the precipice of a smelter!—can be rediscovered by the public.

From the start, I understood there would be years of work ahead, but the urgency of preserving the images was my greater concern. And even while looking at those sorry mountains of scattered negatives, I could visualize the completed work. The archive is still in progress.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

The unexpected joy in this stewardship is how the project took on a community aspect. My volunteer assistants have been senior citizens with a flair for history and memory. They remember many of the subjects in the photos, and our work together has been as satisfying as it has been productive. We’ve used a space in the library’s Portland Room, and passers-by have watched the project take shape. They ask questions, and the years of banter have forged a fellowship of appreciation for valuing local history. Everyone has stories, and I listen.

When the pandemic forced quarantining, my work on thousands of image scans I’d made from the negatives moved to my dining table. There, I began building digital archives. Digitization and accuracy is demanding; each image has information to be respected.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

Over the past year, I’ve heard from many people who live far from Maine. The comments are profoundly touching. They give me encouragement that I’ve been doing the right things in the right ways, ever since the day I saw those acetate heaps about to be lost forever. These images, these frozen moments in the lives of places and people, are indeed meaningful.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

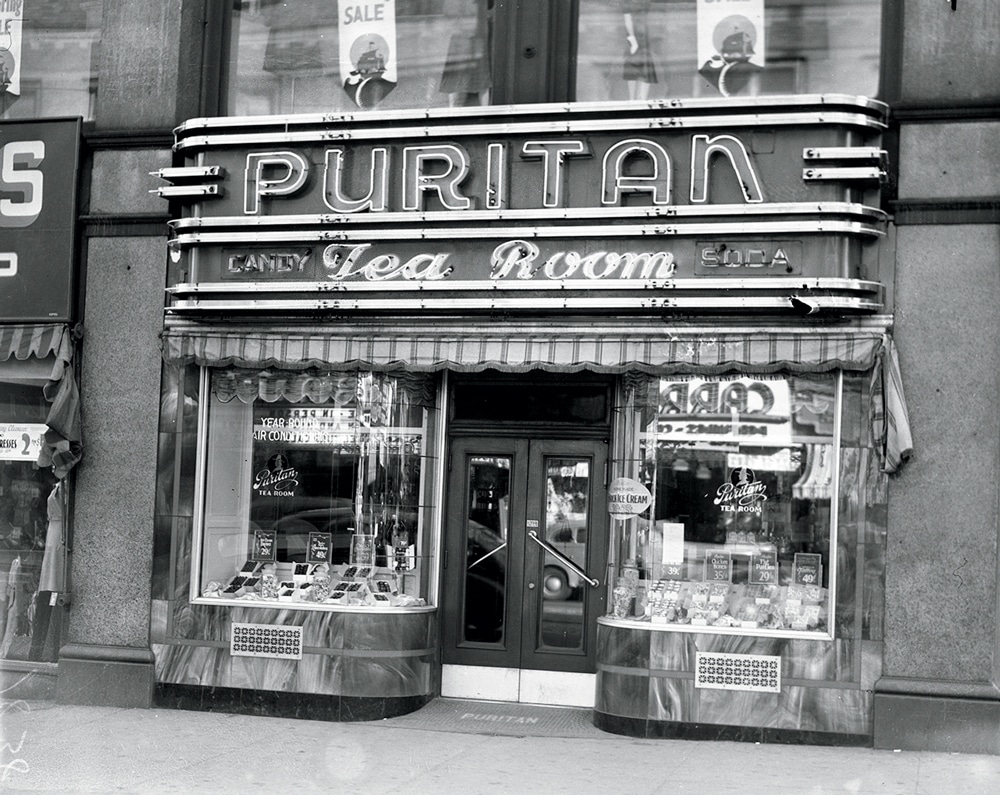

I’ve also been learning about the sustaining power of nostalgia. People tell me about the stores, restaurants, parks, and schools they remember. And I see how a still image can ignite emotional and detailed memories from people far and wide. I digitized and posted a photo of a popular doughnut shop, and another of a delicatessen—and streams of comments followed, regaling me about what everyone loved to order, summer jobs, school days, and family traditions. When I post photos of stores, people tell me about what they bought at these places. One man told me that he had no pictures of his father’s furniture store from decades ago. I found one and posted it, to his great joy.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

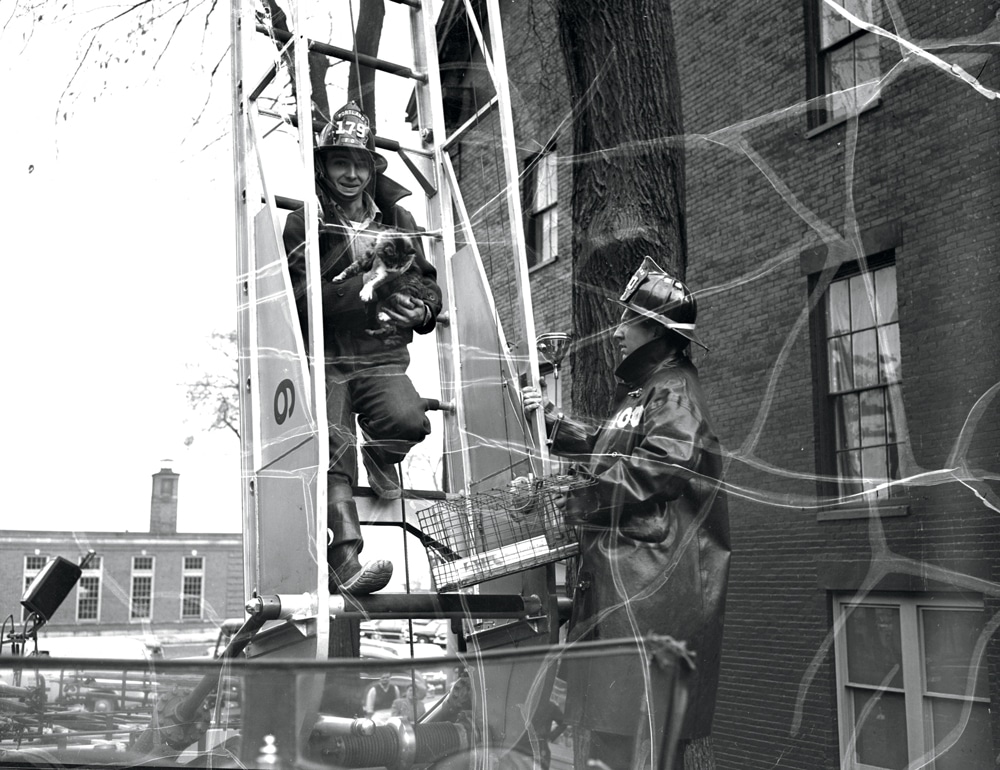

I do not consider nostalgic viewers of archives as different from me. While I’ve been assembling archives out of the film, I’ve been reconstructing a world that is still remembered by many. And I’m part of this, too. These photos restore the histories of people who previously had only their memories to provide images. Anecdotes faded and blurred by time are suddenly sharpened.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

Photography can uniquely say, “Yes, this happened,” and, “It was really there, and so were you.” Archival photographs are evidence, stopping time in the click of a lens shutter.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Portland Public Library Special Collections & Archives

There remains more to do. The Victorian railroad stations, houses and neighborhoods, repair shops, pastries, holidays, events, celebrities, relatives and friends, children’s street games, and big snowstorms are gradually being seen again. We have these worlds, and the more they inspire and instruct, the more they are worth cultivating and conserving.

Go to digitalcommons.portlandlibrary.com/pphnegs to see additional images from Abraham Schechter’s archival photo project. To read more of his writing, go to laviegraphite.blogspot.com.