Magazine

Keeper of the Lighthouse Keeper | Yankee Classic

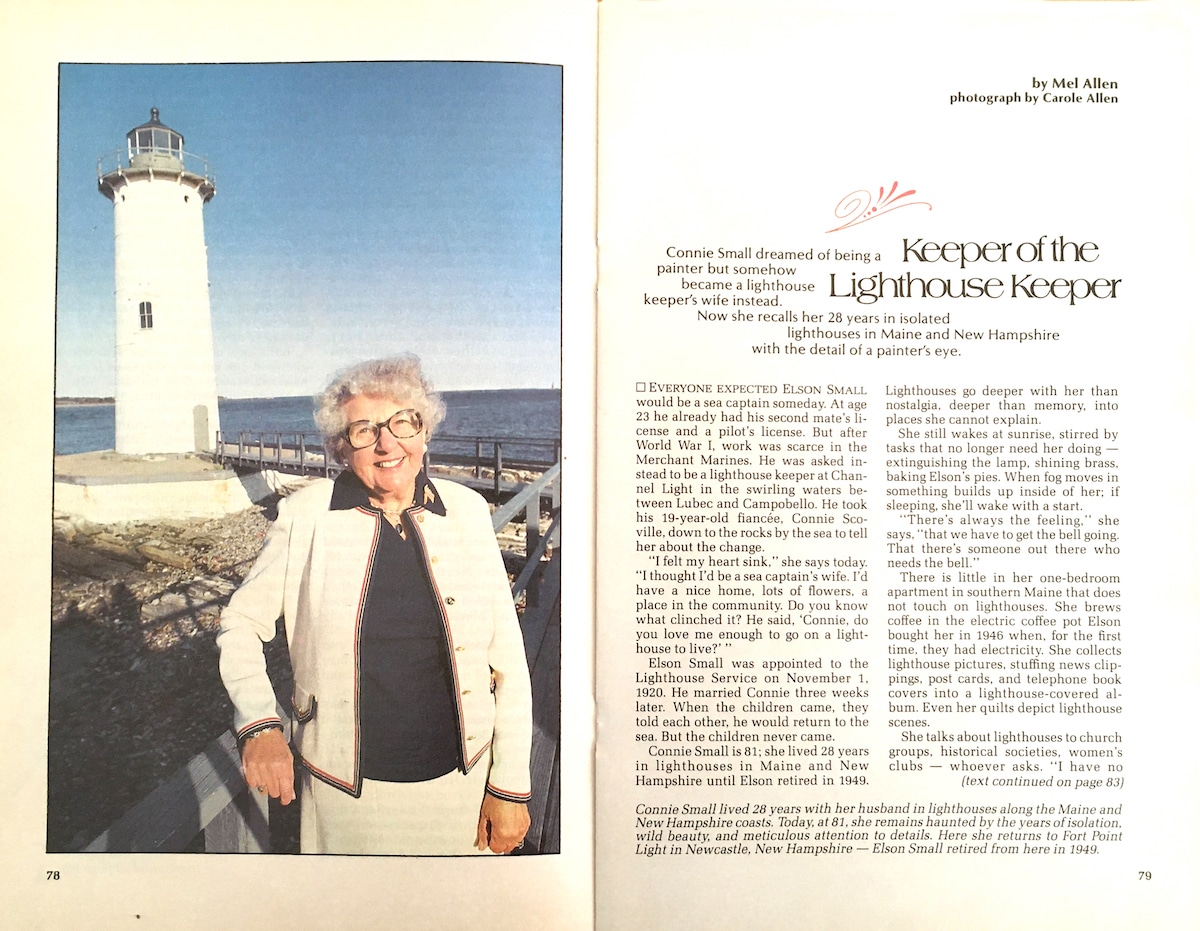

Connie Small dreamed of being a painter but somehow became a lighthouse keeper’s wife instead.

———————————

She is dressed in white with red, white, and blue stripes along her cuffs, and a tiny American flag pinned to her collar. Fresh apple pie and coffee are on the kitchen table. Behind her, casseroles wait for noon company, enough for a crew of shipwrecked sailors. She is telling stories, now and then blurting, “Oh, I talk so much!” and blushing, the color creeping upwards against the white like a sunset striking a house. “I went on Avery’s Rock the tenth of October 1922,” she says, “and didn’t get off until the last of April . . .”———————————

Avery’s Rock, the most desolate station of all, is three miles out in Machias Bay. There was no earth, only a half-acre of boulders and a wooden plank leading from the house to the boat slip. She was 21. There was no phone, no electricity. Rain washed off the roof into cisterns stored beneath the pantry. The lighthouse tender brought coal once a year. If you ran out, there would be no more. Every two weeks Elson rowed to shore for supplies. But the light couldn’t be left alone, so Connie stayed. She saw only Elson, and at night while she knit socks or sewed quilts or bedding or clothes, she’d twist the radio dial, hoping to hear another voice, however faint. The lens was imported from France and they cared for it as they might a baby. It was set in brass, which they polished every day until it shone like gold. “Lots of days we didn’t need to,” she says. “But we liked going up there to see that lens shining.” At dawn they’d extinguish the light, watch the sun creep over the bay, and draw the shades. She cleaned the lens with chamois and covered it with linen. She swept the stairs into a gleaming brass dust pan—“Before breakfast,” she says with satisfaction—“and Elson won the pennant for best light station three years straight.” She baked a pie or a cake every day and fried doughnuts in the morning. She canned fish and wild ducks shot by Elson. When the bloat slip washed away in a storm, a crew of five was sent to repair it. She did their cooking, their laundry, and on Saturday night heated the water so all the men could take their tub baths. She found her social life with pen pals, writing to lighthouse families around the world. “I’d wrack my brains trying to write something from off that rock,” she says. She put the letters she received in a big box lined with oil cloths. Years later, leaving another island and unable to transport it, she buried it. “I felt better then. I wasn’t destroying something that was precious to me.” When Elson became delirious with fever, she tended the light alone through a week of storm. When he recovered, she became ill. “I tried not to give in to it and worry Elson,” she says. “I played checkers with him when his face was just a blur.” Once winching the boat onto the slip she caught her arm under the clamper, crushing it beneath the cogs. “I walked the floor all night. Next day Elson got me to shore. I had to take the mail team nine miles to Machias while Elson returned to the light. For three months I didn’t know I had an arm . . .” She blistered the skin off her hands when Elson was away and a storm erupted and the bell broke down. “I untied the ropes we used to ring the bell by hand when we saluted the lighthouse tender. I pulled for an hour and a half—I knew Elson was out there.” After four years at Avery’s Rock they moved to Seguin, one of the largest lights on the coast on a clover-covered island at the mouth of the Kennebec. The foghorn blast vibrated against the window panes of the house 200 yards away. Once, there were three weeks of fog and the horn never stopped. At night sea birds crashed against the tower; in the morning she buried them. In summer she’d be making beds and find tourists staring in through the door. “I’d hide when I heard them coming,” she says. Once a rap on the door brought her face to face with 25 Gloucester gill-netters, whose approach she’d been nervously watching. They asked if she had a radio. “They sprawled all over the living room,” she says, “but there wasn’t a sound. They were listening to the opera.” The next day they returned, bringing her a 65-pound cod. In 1930 they left Seguin as they had arrived—in the fog—moving to Dochet’s Island in the St. Croix River, where they lived for 16 years. Elson bought a cow and plowed a field. They went clamming and at dawn they’d catch flounder and cook them on the boat. Elson lobstered, built boats, and taught Connie target shooting. In winter, ice-bound for weeks, they’d shoot icicles. At night Elson played the banjo. They’d spend two weeks in summer at a Portland hotel, and Connie would walk slowly past the shops before going home to the light. Two days after Pearl Harbor, Elson was asked to cut the Christmas tree for the White House. And soon after, he was asked to serve. “I had three hours’ notice,” she says, “to get supper, pack, and think what private things I had that I didn’t want strangers looking into, then walk out of my house.” Connie stayed in Eastport until January 1945. “You never saw such a happy man,” she says, “when Elson came to the door to tell me we were going back to Dochet’s.” By then the Coast Guard had absorbed the Lighthouse Service, automation had begun, and Elson had only a few years until retirement. He asked for a mainland light. In 1946 they moved to Fort Point Light, or Portsmouth Harbor Light, as it’s sometimes called, in Newcastle, New Hampshire. The house lay inside the fort, the towers just outside the walls on a point jutting into the Piscataqua River. For the first time a bridge connected Elson and Connie to the mainland. When they arrived, the fort was occupied by the army. De-activated bombs were piled higher than her head beside the house. “I tried to figure out a new mode of living,” she says. “I’d never been much with strangers. The light was open to tourists and people came from all directions.” She joined a rug club, sang in a choir. It was their first home with electricity and they went on a buying spree: washing machine, coffee percolator, iron, toaster, refrigerator. “It was heaven,” she says. In June 1949, Elson retired. They bought their first home just across the Maine border in Eliot. “I thought the sea was embedded so deep he’d never turn his back on it,” Connie says, “but he got a tractor and became a gardener. He had the best garden around, and I had a little stand and sold enough to pay for his fertilizer and these rocking chairs.” He built his boats and played a banjo in minstrel shows. Sometimes in winter they’d travel to Florida. They had 11 years before Elson died. “I realized then,” she says, “that I’d lived a protected life. I was very naïve. I could always battle the elements, but I hadn’t been out to battle the world.” In time, after working in a gift shop, Connie became a housemother at Farmington State College, a small co-ed teachers’ college in western Maine. “I was so afraid I would say the wrong thing that for quite a while I just listened and watched. Sometimes they’d come in, very upset to the point of tears, and they’d say could I talk with you, and I’d say of course you can—and they’d sit and I wouldn’t say a word, and they’d get up and say, ‘Oh, you’ve helped me so much.’ “The girls couldn’t understand how I could have devoted my whole life to Elson, how at their age I could have gone off to live like that, without friends,” she says. She sits for a moment, reflecting. “My one great desire was to be a portrait artist. If I could have painted you and have somebody know it was you, I would have been in seventh heaven. I had my paints on the lights. But I’d get so absorbed I’d forget Elson, forget his dinner. I felt I had to make a choice. And the girls could never understand that. Of course,” she says, “I don’t blame them. “Elson was never demonstrative, but I knew he loved me. Very few people depend on each other as we did. He’s been gone 21 years,” she says, “and I haven’t found anyone yet I’d want to replace him with.”———————————

She calls the Coast Guard at Fort Point and asks permission to tour the light. She had been back just once, briefly, 15 years ago. The house was in disrepair, and she’d felt awkward and shy among the men so she left quickly without seeing the tower. From where she parks you can see the house boarded up with gulls circling above. “Somebody’s painted it since I’ve been here,” she says. The house is square, built high off the ground on a concrete foundation, but the stairs are gone. It is late afternoon, and the breeze is nippy, but the sun is out, the sky blue. Several Coast Guardsmen sit on the steps of the station eating pork chops and French fries from plates balanced on their knees. A radio blares, and in the parking lot a man plays basketball alone. She opens an iron gate onto a walkway over the rocks leading to the tower. Scabs of rust show through the paint on the tower. She notes quietly that the curtains are not drawn. “When they first brought the crew in here,” she says, “Elson went up to the tower. He found the lens cover on the floor where they’d been walking on it. It almost broke his heart.” It is airless and dusty inside the tower. She looks at the stars twisting upwards, plants her hand firmly on the railing, and begins to climb. Her steps echo on the iron stairs. Near the top the stairway narrows, becoming much steeper approaching the lens room. “I was always terrified of heights,” she says. “Elson would get behind me. He’d say, ‘Look up, never look down.’ Whenever I get discouraged I still repeat that.” She makes her push into the lens room, breathing hard. In place of linen, a plexiglass tube protects the lens. It is a different lens from the one she knew. She bends over it. “Twenty minutes,” she says. “It took us 20 minutes to light the lamp at Avery’s Rock. We’d time it so it would light just at dusk. It was a vapor lamp and had to be lit just so or it would soot up.” An iron door only three feet high leads to the observation deck. She wriggles through on her knees, her crisp white suit trailing on the ground. The wind is cold, but she stays outside watching the sailboats, her hair blown back, her eyes wide, happy as a colt. “The tankers would pass right by here,” she shouts above the wind. “And there’s the bell I used to ring. I used to do the flags, and the tugboat captains called every morning to see how the visibility was.” She climbs down, her hands gripping the railing. The door is heavy and shuts with a clang. She walks past the house and pauses beside the wall of the fort. “I found a starving cat here,” she says, “its sides caved in. She was wild as a hawk and would run from me. I put food by the bombs and kept staying a little longer, and soon she came to the dish. Soon she brought a young black cat to the back door, and I knew it was hers. I called the young one Blackie. One day Blackie came over the wall with a tiny kitten in her mouth. She laid it in front of me. Four more times she came over the wall and put them all under the bombs. Each morning I’d look under the bombs and see five little pairs of eyes looking back. It was an icy winter so Elson built a house for them on our porch. “One dark morning I heard a terrible yowling. It was Blackie. I swear she was trying to talk to me. I saw right off the kittens were gone. She would go a little ways, holler, and wait for me to come. I followed her all over the place that day and every day for a month. But we never saw those kittens again. We figured wild dogs had run them into the river. “Blackie stayed with me, but she never let me touch her. When we left we couldn’t catch her to take her with us. I came on the steps for the last time and sat down. I called to her. She came running from around the house and jumped right into my lap! I was so surprised I went to put my hand on her —but she was gone. You know,” she says, walking away, “I never once got my hands on her.”———————————

She goes home and makes coffee and brings her albums back to the sofa. She shows Avery’s Rock, gray and stark, later dynamited by the government to keep vandals away. She shows Dochet’s Island, burned to the ground by vandals. “I told them they were making a mistake when they took families off those lights,” she says. It’s twilight and her voice is tired, her face flushed from the day. She draws the curtains. She turns on a lamp on top of the television. On its side is a painting of a lighthouse and storm-tossed sea. A tiny light revolves behind the painting. The sea appears to surge, and a light pulses from the tower. She sits in her rocker in the dark and watches.