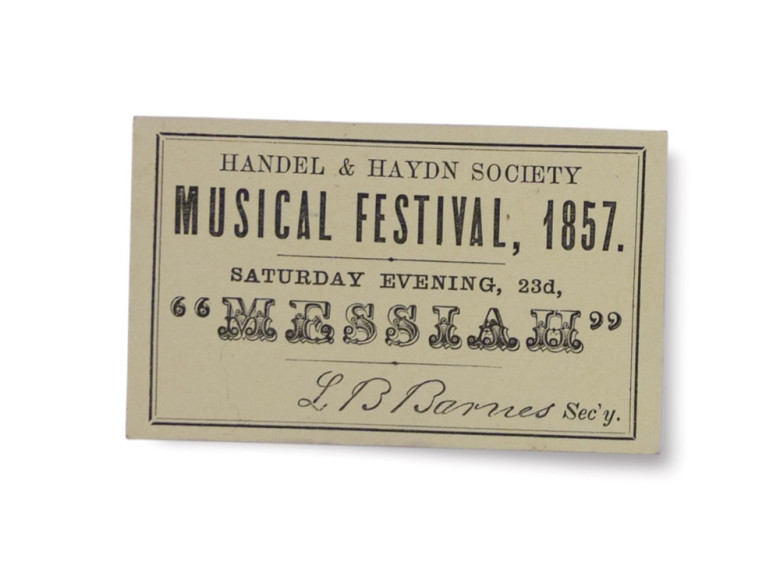

The Ensemble Liveth | Handel and Haydn Society’s Messiah

Handel and Haydn Society’s Messiah remains unmatched.

The Handel and Haydn Society’s Messiah is one of Boston’s most-loved holiday traditions. Here, Artistic Director Harry Christophers (center),

the musicians, and the singers take a bow.

By Colin Fleming

Photo Credit : Stu Rosner

Late November, and for weeks Boston has been bedecked in wreaths and laurels. Across the street from the storied Symphony Hall, the city’s other lyrical little bandbox, musicians have assembled in what looks like a high school classroom. They are dressed casually. A cell phone rests on top of a harpsichord. A couple of Trader Joe’s tote bags lean against music stands. The musicians—members of the Handel and Haydn Society orchestra, and several solo singers—chat amongst themselves, before a peppy, friendly English voice—that of conductor Harry Christophers—says, “Right, then. It’s Messiah time again, yes? Here we go.”

Even if you are not a fan of classical music, chances are you have attended at least a piecemeal performance of Handel’s 1741 oratorio. If you live in New England, odds are excellent that you have seen a performance from the Handel and Haydn Society. Or perhaps you are one of those people who view the holidays as incomplete without experiencing one of the world’s most beloved classical works, delivered by a group who perhaps renders it better than any.

They’ve certainly had time to get matters in order. On Christmas Day 1815, 90 male singers and ten female singers arrived at King’s Chapel for the first Society performance. The members came from local churches, an area all-star team of performers. Local papers reported deafening applause.

Harry Christophers, born the day after Christmas 1953, has been helming the Society since September 2008. He is an energetic leader, stopping this first rehearsal to make an illustrative point, then leading everyone back into the charge.

“There are very few pieces, particularly from Baroque and Classical period times”—in other words, the periods the Society specializes in—“that have maintained popularity like Messiah,” Christophers remarks, a few days later, in the offices of H&H. “I don’t find it that difficult to keep it fresh. I think part of the problem is that there are some singers and musicians across the world who think, ‘It’s Messiah time, that’s kind of boring,’ because they do it every year. But that’s not our kind of performer, frankly. There should never be anything boring about Messiah.”

Handel wrote the work in a blaze of creativity in less than one month. We tend to associate it with Christmas, but as Christophers points out, “It was really a piece for all seasons, and one that became particularly associated with charity, with giving.” It is, essentially, the life of Christ in musical form, the soup-to-nuts treatment, from birth to death to resurrection. All in a tidy couple of hours.

Christophers selects four new soloists each year. Last year one was contralto Emily Marvosh, who returns regularly to the Society fold. Messiah is in English, but the language was not Handel’s native tongue, which results in some highly individualistic turns of phrase.

“There are these quirks in the language at times,” Marvosh offers, “that keep things wonderfully new for a singer. Handel maybe thought something meant something a little different, but the words have a musicality to them, and Harry always brings out something new, too.”

After the four soloists and the orchestra, the chorus and organist have their rehearsal, before everyone gathers the next day for a full-group run-through. Christophers is quick to remind everyone that “There’s always someone hearing us for the first time. Let’s always remember that, yes?”

Christophers is abetted in his conducting efforts by his brilliant concertmaster, Aisslinn Nosky. Anyone seeing her remembers her shock of red hair and expressive body movements as she plays her violin at a level few approach. Sometimes she stops the rehearsals, too, offering a point of clarification, stating that a note be held for an extra fraction of a beat. Christophers conducts sans baton, very spryly, like he’s involved in an athletic pursuit where nimbleness is the crucial criterion. He and Nosky exchange barely perceptible glances at certain points, and after two days of rehearsals—the final of which is open to special Society guests—Christophers halts the music, and says, “I think we’re all set, then. See everybody tomorrow.”

It is still not concert time. First, there is a last rehearsal, in full dress—for this is also a photo shoot—at the vaunted Symphony Hall. Violinist Jesse Irons, a relative newcomer by Society standards, having appeared on a handful of Messiah performances, says, “You never want to rehearse where you sound great, like in Symphony Hall, with perfect acoustics. But when we get here, wow. The dynamics of the sound can just blow you away.”

More special guests occupy the orchestra section of seating. Christophers walks down a ramp, as Nosky and the strings play on seamlessly, and walks toward the few people in attendance, so that he can hear what they are hearing, and determine if anything is off, acoustically. The near-empty hall is a singular sight. People commonly fail to note how narrow it is, which works like one of those wind corridors near Government Center, channeling the music straight at you, through you. Witnessing the rehearsals, you become aware of how emotionally taxing this work is, how much it asks musicians to give of themselves. And despite the musical and emotional range of Messiah, performance hiccups are virtually nonexistent.

There are people in their eighties who have been coming for 60 years, small children in their holiday finest with their first Messiah memories about to be made, young couples having decided to invest themselves in some rich musical culture, in this, the season of office parties, rebroadcasts of Griswold misadventures, and family gatherings.

If you know but two pieces of classical music, they are undoubtedly the chorus from Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and the Hallelujah movement from Messiah. You encounter the latter, even by accident, dozens of times a year. It comes relatively close to the end of Messiah, and it’s what a lot of people most wish to hear. Sometimes, having heard it, they leave, which is a big mistake in these matters. For as stunning as the Hallelujah chorus is, it is not the most moving portion of the oratorio, not nearly. Handel saved that for the end, and Christophers and the Handel and Haydn Society save their best for the end, too.

Emily Marvosh says, “For me, the most amazing moment I’ve had doing Messiah with Handel and Haydn was one time, during the final Amen chorus, when there was this brief pause, and Aisslinn’s head went down, and then back up again, and everyone, the orchestra, the chorus, just became this one interlocked musical creation.”

That closing Amen chorus is one of the great achievements in the history of Western musical culture, with Handel taking a single word, and, from it, ringing whole new worlds, with but two syllables, some singers, and some players. Whether you have hope and gladness in your heart, or despair and faltering hope that things will get better—for such can be the emotional range of the Christmas season—you will connect, in your way, with this final movement, especially with how the Society handles it, and you will walk back out into the cold all the better for it.

For this special occasion of Messiah performances for the Society’s bicentennial, there is a new wrinkle on the final section. “I did not see that coming,” Irons remarks backstage afterward, his eyes still watery with tears. He is referring to a look Christophers gave to the four soloists, to stand and join in the final chorus, which is not the norm. Voices ring out from everywhere, as if in an attempt to remove the roof from Symphony Hall, and get out into the streets, where the green bedecked city awaits.

“I don’t think we’ve ever done that,” Irons says. “Some people might think it’s cheesy.” A devoted Scrooge, perhaps. “But you can’t deny that if it is, that’s good cheese.”

Amen to that.

For more information, visit: handelandhaydn.org