Spotted Lanternflies: Help Defeat New England’s Public Bug Enemy No. 1

If you appreciate the beauty of New England’s forests and enjoy eating agricultural crops like apples, the time to swing into action to stop these invaders is now.

Be on the lookout for the invasive spotted lanternfly, and, if you see one, our bug expert says: Squish it.

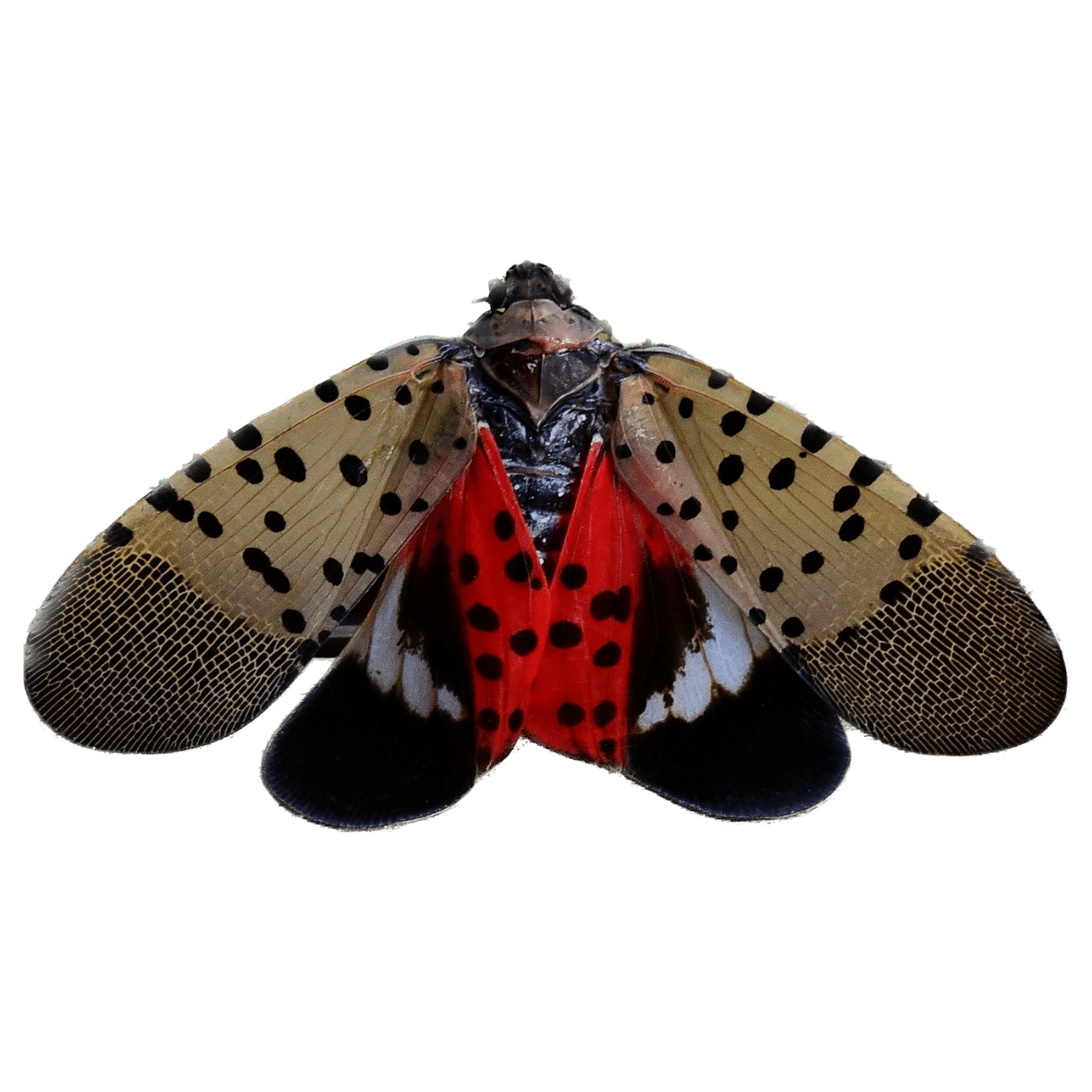

Photo Credit : slgckgc/FlickrThe spotted lanternfly is quickly gaining ground in New England. And the threat these invasive bugs present to cherished crops and the natural landscape is real. We spoke with Zac Smith-Hess, entomologist and educator at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens, to better understand where spotted lanternflies came from, how fast they are spreading, how harmful they are, and what urgent action we need to take to stop them from destroying things we love about New England—like fall foliage season.

Q: What sort of a bug is the spotted lanternfly?

A: The spotted lanternfly is a true bug. It’s a leafhopper, specifically. They’re found all over the world. The tropics have some really incredible lanternflies. This particular one is from northern China and Vietnam. That’s its native habitat. It has spread to Korea and Japan, as well.

Q: When did spotted lanternflies begin their U.S. invasion?

A: The spotted lanternfly was first officially recorded in Pennsylvania in 2014. It’s believed they came in on a shipment of landscaping stone from China. In the process of discovering that, investigators found numerous hatched eggs. So, we think it may have actually been here around 2012 or so.

Q: Are spotted lanternflies harmful for humans and pets? Is there anything we need to be worried about?

A: They are not harmful for humans or pets—no. A lot of animals that have that bright red, black, and white coloration, it screams: “I’m toxic.” For the lanternflies, that is a fakeout. They’re just pretending to be poisonous. That is the good news.

Q: Then why are we so worried about spotted lanternflies here in New England?

A: They spread rapidly. I just read a paper that called them “the most invasive insect that the U.S. has seen in about 200 years.” They are a big problem. They target two big groups that we’re worried about. They go after a lot of crops, so anything in the rose family; they’ll go after soybeans; they go after stone fruit, grapes, apples, all sorts of good food crops. And then, they also hit our big forest trees. They are attracted to oaks, maples, pines, poplar, sycamore, willow, all sorts of different trees. They actually hit about 173 different plants all together.

Q: How do spotted lanternflies do their dastardly damage to these plants and trees?

A: The main problem isn’t anything they are doing specifically. They do attack and drink the sap from trees, which does damage them. But if it’s a healthy tree, it should be just fine. The issue is that when they are feeding, they actually produce huge amounts of honeydew. That honeydew encourages a lot of mold growth and fungal infestations, which can cause a downturn for the plants.

Q: What sort of a timeline are we talking about?

A: It really depends on the amount of lanternflies. In some cases, we’re seeing thousands and thousands of individuals on single trees. That will cause some pretty rapid damage. A real heavy infestation could kill a tree in a year.

Q: Why isn’t this a problem in places where spotted lanternflies are native?

A: There’s a parasitoid wasp that attacks them as an egg. It actually lays its eggs inside of their eggs, which helps take care of it. And then there are two fungi that also attack them. So, they have all sorts of natural predators in their native areas.

Q: Is a spotted lanternfly easy to identify? Can it be confused with anything else?

A: There is nothing else that looks like this. Nothing with the gray wing covers with the black spots with the bold red underwing. It’s easy to identify.

Q: What should I do if I see one? Are we really supposed to kill on sight and ask questions later?

A: Yeah, pretty much it’s kill on sight. There are a couple of techniques that people have trialed. Honestly, the best thing is just to step on them. Just squish them. It’s effective. It’s easy. Just do it whenever you see them.

There’s also a fun little trick with a water bottle that a lot of people are doing. If you take an empty water bottle and hold it up to the lanternfly’s head, it is going to instinctively jump straight back into that water bottle. It makes them easy to collect.

Really, though, the best way we can target them is when they’re eggs. Their egg masses are pale gray. They look like fish scales covered in a thin layer of mud. The best thing we can do with eggs is just scrape them off and into a container that holds either hand sanitizer or rubbing alcohol to definitely ensure those eggs will die. If we can target them as eggs, we’re in good shape.

Photo Credit : Kim Knox Beckius

Q: Where are spotted lanternflies in New England now?

A: There are 14 U.S. states where they actually have an established population, including Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts. They have not been found established in New Hampshire or Vermont. They have been sighted, but they haven’t been established. And that’s where we are in Maine, too. Egg masses were found in Wells this past November. They were observed, destroyed, taken care of. However, last summer, it made it from one sighting in Massachusetts to being fully established in 13 counties in Massachusetts in one season.

Q: Wow. How fast are spotted lanternflies reproducing and spreading?

A: Quickly! Females can lay about 30 to 100 eggs. Most of the time, they reproduce just once in a year, but they can do it more than once if it’s a good place and a good season… if everything lines up just right. We thought for a while that they were really closely tied to an invasive tree: tree of heaven. Unfortunately, it turns out that while they are more successful if tree of heaven is around, it doesn’t limit where they’re able to go. So they can complete their life cycle on other plants. But they do really like to target this tree. It’s their favorite. Tree of heaven is native to the same area the lanternfly is: East Asia. They are one of the most invasive plants in the country, too. So they go hand-in-hand.

Q: On a larger scale, what is being done by universities, organizations, agencies? Is there someone taking the lead on this?

A: Yes, Pennsylvania, and specifically Penn State has incredible resources on identification and management of spotted lanternflies. They’ve been the heart of it since the very beginning. I highly recommend their spotted lanternfly resources. They have great, easy-to-navigate, very bold programs on lanternflies.

Q: Is there a global solution?

A: Bringing in parasitoid wasps is one option people are exploring. The fun thing about parastic wasps, if there can be such a thing, is that a lot of them are really specific, so they only target one species. It turns out that spotted lanternfly has a wasp that only targets spotted lanternflies. We have not released it: They are currently doing trials in Pennsylvania to see if it is an effective management. That’s still done in labs. We’re not doing any field trials or things like that yet.

Q: What would you say to someone who thinks, “Spottled lanternflies are not MY problem”?

A: Spotted lanternflies could have a major impact on our food. It’s estimated that it is costing Pennsylvania alone in the hundreds of millions of dollars every year in agricultural losses. It’s directly impacting our food supply. And then think of all of those beautiful forests, all of those nice forest trees. They can also be severely damaged by spotted lanternflies.

Q: What else should people know? Is there anything that makes you hopeful we can defeat these invaders?

A: Some good news! Rutgers did a big study, and they came across two key facts. One is if spotted lanternfly eggs are exposed to -13 degrees Fahrenheit, they die. So, great news. We know that they cannot sustain anything at -13 or below, which puts Maine in pretty good shape. Those cold days and cold nights are becoming rarer, but we still drop below that level pretty frequently. And after about -5 degrees Fahrenheit, we see a major decrease in the amount of successful hatches from individual eggs. So low temperatures can really help limit the spread. The twin issues of invasive species and climate change are very hard to pull apart.

SEE MORE:

How Invasive Pests and Plants Are a Threat to Fall Foliage

Plants That Repel Insects and Garden Pests

Invasive Plant Species in New England

Have you seen a spotted lanternfly? Tell us where below.

Kim Knox Beckius

Kim Knox Beckius is Yankee Magazine's Travel & Branded Content Editor. A longtime freelance writer/photographer and Yankee contributing editor based in Connecticut, she has explored every corner of the region while writing six books on travel in the Northeast and contributing updates to New England guidebooks published by Fodor's, Frommer's, and Michelin. For more than 20 years, Kim served as New England Travel Expert for TripSavvy (formerly About.com). She is a member of the Society of American Travel Writers (SATW) and is frequently called on by the media to discuss New England travel and events. She is likely the only person who has hugged both Art Garfunkel and a baby moose.

More by Kim Knox Beckius