Build a Compost Bin

A Maine gardener discovers how to make rich, nutrient-filled humus the easy way. Fred Davis knows the value of good compost. For 24 years, he and his wife, Linda, have owned and operated a nursery, Hill Gardens of Maine, at their home in Palermo, about 15 miles northeast of Augusta. Early on in the venture, Davis […]

Step 3

Photo Credit : John BurgoyneA Maine gardener discovers how to make rich, nutrient-filled humus the easy way.

Fred Davis knows the value of good compost. For 24 years, he and his wife, Linda, have owned and operated a nursery, Hill Gardens of Maine, at their home in Palermo, about 15 miles northeast of Augusta. Early on in the venture, Davis discovered two important things about himself: He disliked paying for compost, and he didn’t care for the work required to make his own. So, in 1987, sparked by a magazine ad for a hassle-free, no-turn compost bin, he decided to build his own compost bin out of wood pallets and plastic drain pipe. The result: a rich, ready-to-use cubic yard of compost in weeks, not months.

Process to Build a Compost Bin

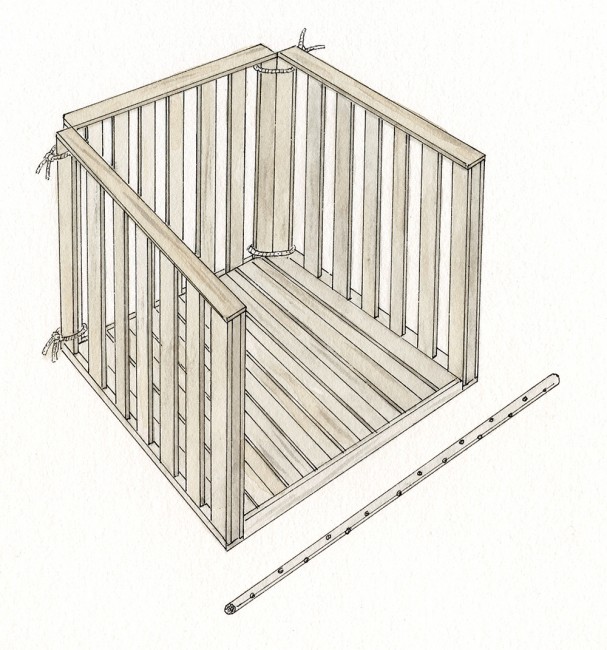

Step 1: Davis uses four salvaged wooden pallets for the box frame and one as a base to provide air flow to the bottom and deter any tree roots fishing for nutrients and water. For the sides, he stands the pallets up, keeping the slats vertical and lashing them together with plastic clothesline cord tied in square knots at the top and bottom corners.

Photo Credit : John Burgoyne

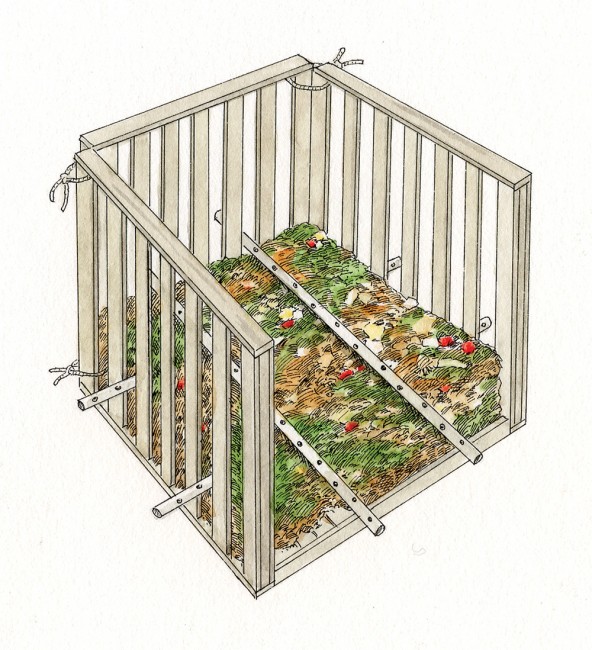

Step 2: From there, Davis creates a shredded mix out of browns (leaves and pine needles) and greens (grass clippings), kitchen waste, and a pail of horse manure. But unlike other composting methods, this one doesn’t require that he shovel it in all at once. Instead, he adds the material in six-inch layers, each topped with a sprinkling of bone meal for added phosphorous and enough water to moisten the layer to the consistency of a wrung-out kitchen sponge, all to help the bacteria move and consume.

Photo Credit : John Burgoyne

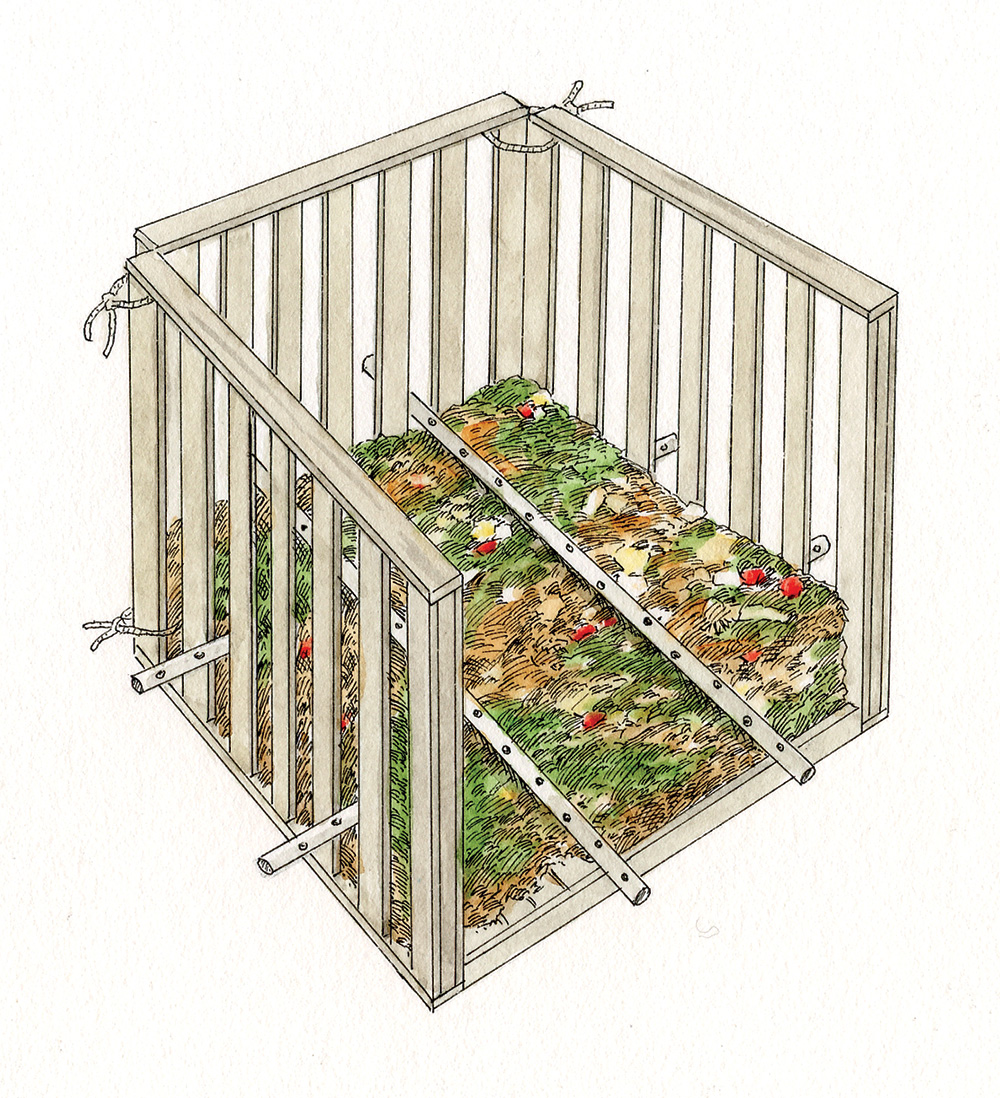

Step 3: Then atop and across each section, Davis also lays out two 4.5-foot pieces of plastic drainpipe that he’s perforated with half-inch drill holes every 3 to 4 inches all around. The tubing, measuring 1.25 to 1.5 inches in diameter and spaced 16 inches in from the bin’s sides, is long enough to stick out of the box a good 6 inches. Why the perforated pipe? “Hot-rot biological composting requires air,” he explains, “to support the aerobic bacteria that digest organic matter into compost.”

Photo Credit : John Burgoyne

Step 4: To finish the job, Davis builds more layers and positions more pipe, each set laid out at right angles to the previous one. At the top of the bin, he adds a 4- to 5-inch insulating bed of pine needles and whole leaves. Within four days, the center of the pile reaches 155 to 160 degrees, more than hot enough to kill weed seeds and most plant diseases. To be sure that those hot temperatures circulate to the material near the perforations, where cool air is constantly pouring into the mix, Davis plugs the ends with newspaper or leaves for just a single 24-hour period three days into the composting.Then he waits. After three weeks, when the pile is half its original size and its core temperature equals the ambient air temperature, Davis has new compost. He gives the pile another week or two to settle and stabilize; then he’s ready to garden. “If you put two of these bins side by side,” he says, “you can have new compost nearly every other week.”

WHAT DO YOU LIKE MOST?

After more than 20 years of composting this way, the proof is in the dirt, Davis says. “Normal soil is 10 percent organic matter,” he notes. “A typical home gardener’s is 15. Most of my two acres of garden soil is 75.”

COST:

$60 for piping, pallets, and clothesline; plus compost thermometer, $24.95 at Johnny’s Selected Seeds, Winslow, ME. 877-564-6697; johnnyseeds.com

Have you completed a home project that you’d like to see in Yankee Plus? We’ll pay $100 for every one selected. Email: Plus@YankeePub.com