The Throwback | Steve Smith of Renaissance Timber in Cumberland, Maine

Using only an ax, Steve Smith resurrects the centuries-old craft of hand-hewing to bring both history and new life into today’s homes.

Smith holds a bearded broad ax that he had custom-forged by another Maine traditionalist, blacksmith Nick Downing.

Photo Credit : Stacie MaddoxBy Nina MacLaughlin

The thunk comes first, the sound of ax through wood. It’s a sound that registers in the body as much as the ears, a sound that one feels in the center of oneself: the exchange between blade and trunk, forces of muscle, bone, gravity, and tree, and then the whisper of wood-chip shrapnel landing on the grass.

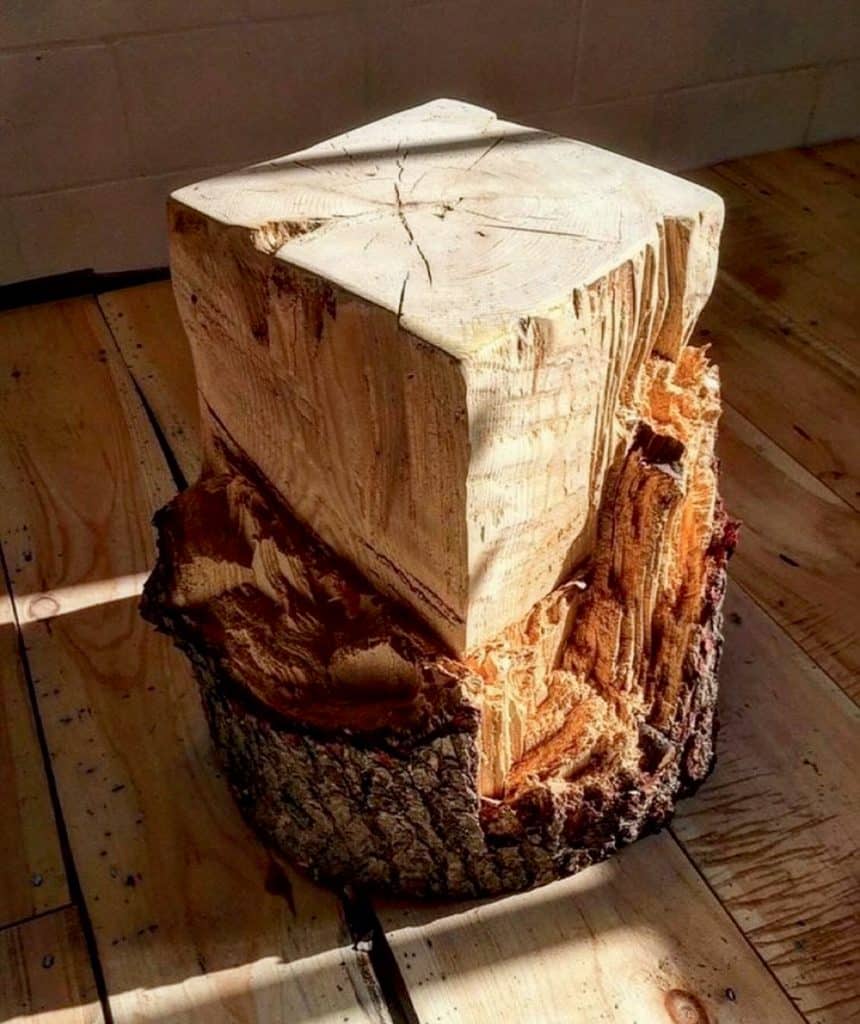

Such is the aural landscape of Renaissance Timber in Cumberland, Maine, where Steve Smith practices the craft of hand-hewing, taking the round trunk of a tree and shaping it into a square beam. No power tools, no screaming saws or spinning blades. Just his body, the tree’s body, the ax.

And what results—structural beams and mantels of white pine, cedar, cherry, oak—breathe with life and history. They take their places in homes, above the hearth or supporting the ceiling, and become part of the soul of the place. They draw the eye, and more than the eye.

“People are homesick for imperfection,” says Smith. Every mark you see on one of his beams was a decision, part of an intimate connection between man and tree. “It’s a conversation between souls,” he says. And that conversation reverberates, providing a palpable sense of warmth absent from the sterility of industrialized perfection. And it will last longer, too.

Photo Credit : Steve Smith

Photo Credit : Brian Threlkeld

Smith, 43, talks of the planned obsolescence of modern-day building materials. “The stuff I’m making will be here 200 years from now,” he says, the wood speaking to the future as well as the past in its rough Maine vernacular. It’s a legacy item, he says, and to be in a room with wood he’s hewed is to “step into the river of history. It gives a sense of movement in a way that sheetrock doesn’t.”

Smith’s evolution as a hand-hewer has its roots in the past as well. His great-great-grandfather drove logs downriver in Maine; another sold used lumber. And Renaissance Timber is based on the farm where Smith grew up. A sense of heritage is important to him, the circle of life and growth and connection. When we met, he’d just finished building a small cabin playhouse for his two boys and was readying to turn the front section of the dairy barn into a showroom. The trees he uses come from his land, or that of his clients; the carbon footprint of his work is zero.

We met on a bright, warm September afternoon, the autumn equinox, and Smith was hewing a tree by the barn as the sun made the grasses glow gold in the field to the south. He’d marked the edges and snapped chalk lines down the length of the trunk; he’d stood on one side of the tree and axed a series of wide notches, concave openings every 18 inches or so. And then, with left knee resting on the log and right foot planted on the ground, he raised the ax and brought it down, that great deep thunk, jogging out the sections between the wide inviting openings, fragments of wood flying through the afternoon light.

Broad of shoulder, thick of bicep, Smith does not have the vanity-driven chiseled form of a gym-goer but the full-body strength of someone who uses that body for his work. It hasn’t always been so: He’s relatively new to hand-hewing, having started the business in 2019. Working a white-collar job, he tore his bicep lifting something heavy, tweaked his back logging so many hours at a desk, and worse, knew the staticky fuzz of being in front of a screen all day. Then a book crossed his path, A Reverence for Wood by Eric Sloane, and he watched the hewing process on YouTube. He took down a cedar and gave it a shot. “It resonated,” he said. While his days in front of a screen blurred together as one, “I remember every place I’ve been in the woods for clients. I remember the bugs, the temperature, the light.”

Photo Credit : Brian Threlkeld

Smith carries himself with the humility of someone who’s asked himself the hard questions, recognized the painful fact that how he’d understood the world was wrong, and had the courage to make a change. He has the spark in his eye that people who are in intimate relationship with the land have, the glow that comes from the source. We sat on one of his beams—a chipmunk scurried nearby, the back door of the barn framing the field outside—and Smith spoke of the connection the work brings him with the natural world, the tactile satisfactions, the five-sensed attunement to the shifting light, the creatures and the birds, the smell in the air before it snows, the wind speaking through the trees.

There is meaning in his work, a sense of peace and place, and each beam he hews communicates exactly that, and the mysteries of our bodies in time. “Part of what surprises me about the work,” he says, “is the sense of wonder it brings, of being fully alive. It reminds me of childhood. I’m interacting with the world on its terms.”

In addition to mantels and beams, Renaissance Timber offers hewn benches, centerpieces, and trenchers, as well as handcrafted cutting boards. To learn more, go to renaissancetimberllc.com.