Bertha’s Journey | First Person

Richard Adams Carey reflects on watching a snapping turtle take a leap of faith.

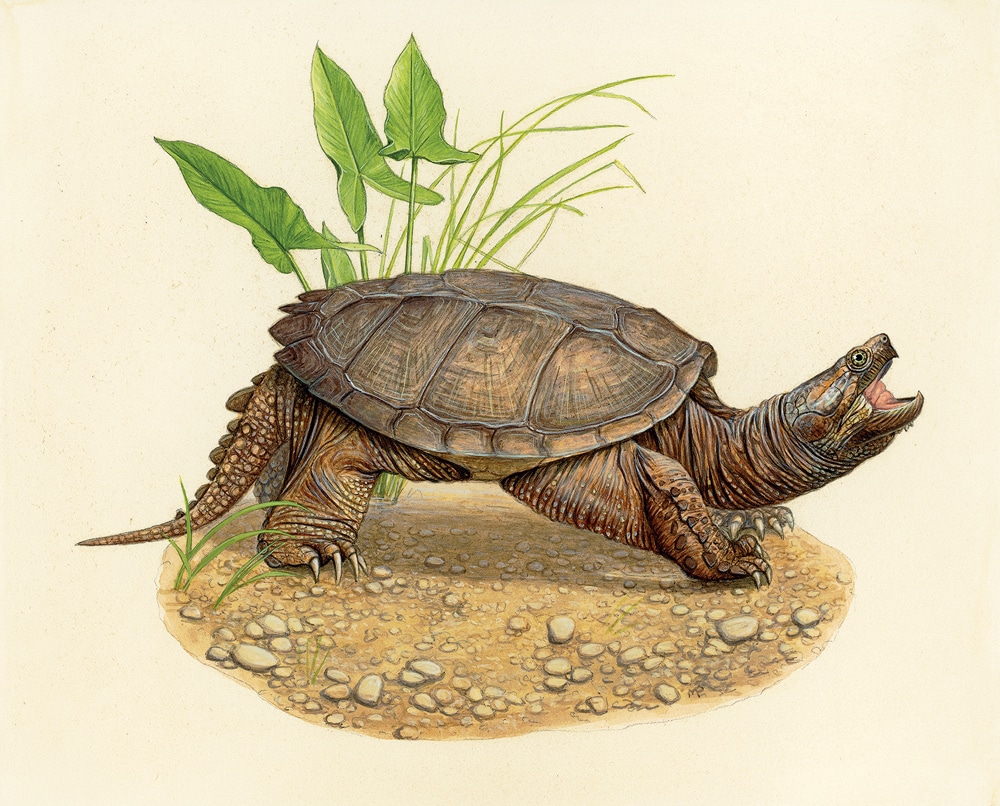

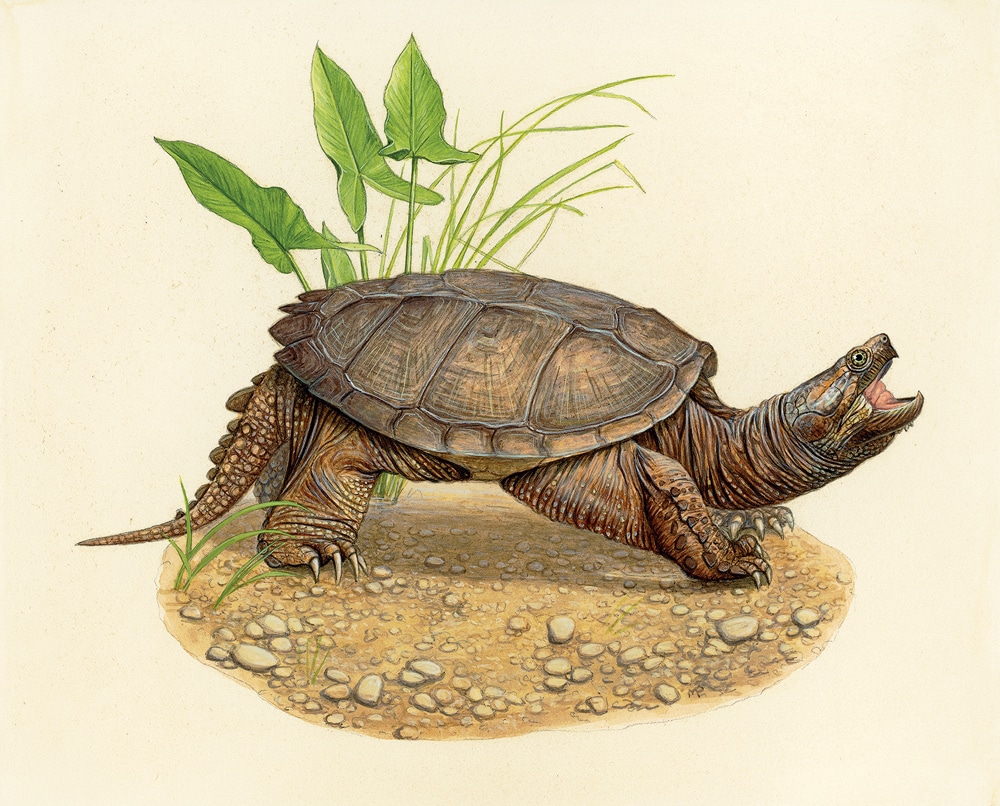

Bertha’s Journey

Photo Credit : Matt Patterson

Photo Credit : Matt Patterson

Each winter we wonder about this creature entombed in the ice of our pond out back. Snapping turtles are cold-tolerant, and they don’t necessarily hibernate, but often they do, burrowing like clams into the bottom, only their beaked heads exposed, not breathing, per se, but somehow teasing oxygen from the water through the membranes of the mouth and throat.

We can’t imagine what Bertha would do otherwise in that little pond. We wonder how she endures such cold. We wonder what she thinks or dreams about in a twilight inaccessible to those who live strictly on either side of that border between sleep and wakefulness.

We call her Bertha because that’s what the previous owners of this home in Sandwich, New Hampshire, dubbed her. Not always, but often, once the ice has melted, we see some part of her overland journey from the back pond to the front yard, to Church Street, and then—where? It would be easy enough to find out. She can’t outrun us. Instead we leave her in peace after we halt traffic, if necessary, to see her safely across the road.

We know it’s Bertha each year thanks to a scar on her carapace that might be the result of an unchaperoned encounter with a car. We also have a theory about where she goes: to that bigger pond behind town hall, only a quarter mile distant. We presumed she was on her way to lay eggs near there, but eventually we remembered that midsummer is when snappers do that. Instead, in the spring, they go abroad to look for love, or to change their address, or maybe both.

We wonder if Bertha summers in that bigger pond. Perhaps she has a fond companion there, at least during breeding season. She might not even be a Bertha—more like a Bert. We just choose to imagine her as feminine, dressing her up in unwarranted maternity clothes as this lumbering, prehistoric beast reminds us each year (a little ahead of Mother’s Day) that this earth is deeper and older than we can imagine.

And stranger. We read in the literature that snapping turtles can journey up to 10 miles to find whatever it is they wish to find. Bertha may have only just begun by the time she crosses Church Street. Yet how do they find Zion, given that a turtle can hardly see over the next clump of grass? The earth’s magnetic field has something to do with it, but in its details this is a mystery to an errant species that has found its way to the moon and back but can also get lost in a mall.

My wife and I know that Bertha’s built-in GPS, however, lacks the alternate-route flexibility of Google Maps. We had always thought she went via the smooth lawn on the east side of the house to reach Church, but last spring Sue happened to witness this part of the journey from our back porch. She has the photos to prove that Bertha goes west—where a tumbledown stone wall intervenes.

You’d think you were safe from turtles, if nothing else, on the street side of this wall. But Sue watched in amazement as Bertha’s bearlike claws took her up the near-vertical face of one boulder, and then a second and a third. At the summit, after a good long rest, she dug all four feet simultaneously into granite and launched herself into space. Like an air-dropped shipping container, she fell clattering but upright to the gravel below. Then on to Church Street.

I might not have believed this if not for the photos. Incredulous herself, Sue went out front to direct traffic. One driver rolled down her window to ask, “Is that your pet turtle?”

But Bertha is nobody’s pet, and possibly nobody’s girl. For the latter, we only hope it’s so. If turtles, like dinosaurs, ever learn to fly, this is where it began.