Caretaker to the Old Man of the Mountain | Yankee Classic

Before New Hampshire’s symbol fell on May 3, 2003, Niels Nielsen acted as caretaker for the Old Man of the Mountain for decades.

Excerpt from “The Old Man Comes Down from the Mountain,” Yankee Magazine, July 1991.

In 1959, Niels Nielsen moved to New Hampshire from Brooklyn, New York, to join the highway department. Two weeks after starting the job, he made his first trek to the top of New Hampshire’s Old Man of the Mountain, a 40-foot-tall rock formation on Cannon Mountain, some 1,200 feet above Profile Lake.

“I had sailed around the world as a merchant seaman,” he said, “yet I had never seen anything like the Old Man. I don’t believe anyone can be up there and not feel the presence of God.”

Though Niels believes the stone profile is God’s work, keeping it stuck to the mountain is man’s doing. The Old Man’s head is made up of a half dozen randomly placed and precariously perched boulders. They are held in place by a web of steel cables called tie-rods, each about nine feet long with a holding strength of 109 tons and linked by adjustable steel joints called turn buckles. These are mounted to foot-high U-bolts anchored to the granite. The current strain on the tie-rods is tested with a simple thermometer — one degree warmer means an extra ton of stress.

“The Old Man heaves and sighs with changes in temperature,” Niels had told me. “The forehead rocks back and forth. The turnbuckles act as hinges, so he has a little bit of space to move, but not a lot.”

Photo Credit : Photographer unknown. Originally published July 1991.

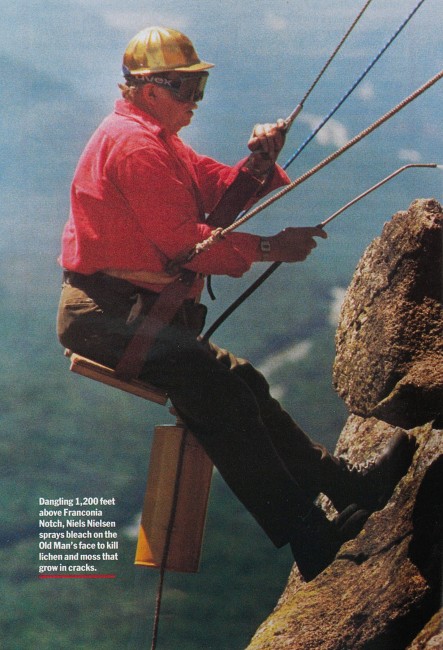

Since 1965, Niels, a bridge maintenance and construction supervisor, has also been the Old Man’s caretaker. At six feet five and 250 pounds, he’s the right man for the job. Every year he has trekked to the top of the great stone face to check the Old Man’s condition. He measures every shift in the rocks, takes strain tests on the turnbuckles, repaints them to prevent rust, and seals cracks in the rocks. He hangs over the Old Man’s forehead in a bos’n’s chair, a sheer drop below, and washes away the effects of acid rain to ensure the face doesn’t crumble. Then he cleans out the Old Man’s ear with a garden hoe.

When his son David was young, Niels encouraged him to come along by asking the boy to help give the Old Man a haircut and a shave. Now 32, David brings his own son, Tommy, who is 11.

Last summer I joined the three generations on a trip to the top. It was Niels’s 63rd birthday. Also along were five men from the New Hampshire Parks Department and his daughter-in-law, Deborah. A helicopter dropped us on an eight-foot-square landing pad on top of the mountain.

Niels, dressed in his usual red flannel shirt with an Old Man monogram, led the quarter-mile hike down some rugged topography. We had gone about halfway when he slipped and fell into a crevice. It was a shock to us all, but no one said a word. Niels got up, brushed himself off, and proceeded. A little farther along he stopped and stared in silence at a six-foot gap between two pointed boulders: Decision Rock. You can go around this point by clambering over the rocks, but Niels has been jumping it for 30 years.

“There will come a time when I am too old to do this job,” he has said in the past. “That will be the day I no longer can step across this gap. When I have to go around, that will be my last year.” He looked fit, and I thought for sure he’d make the jump. But Niels just stood there. It was 9:30 A.M., Wednesday, July 25, 1990, and Niels Nielsen had to go around.

When we got to the top, he sat down on the Old Man’s head looking out at the White Mountains. “Will the wind be a problem when you go over the side?” I asked. But Niels just looked off into the distance.

Finally he stood and strapped on a heavy leather safety belt with hook and lanyard. “The Old Man’s more than a pile of rocks to me,” he said. “He is a live thing. I can feel him pulsate when I’m over the side.”

Holding a thin steel cable fed from a grip hoist, Niels rappelled down the Old Man’s brow to spray bleach on the damaging lichen and moss that grow in the cracks of the granite face. “Lower,” Niels shouted up to the man on the grip hoist. “OK, hold it there.”

It was 1805 when Luke Brooks and Francis Whitcomb, pausing to wash their hands in the pond now known as Profile Lake, looked up and were astonished to see the craggy physiognomy outlined against the sky. They thought it resembled President Thomas Jefferson. It became a tourist attraction early, and literary and political notables commented on it. “In the mountains of New Hampshire, God Almighty has hung out a sign to show that there He makes men,” bragged Daniel Webster.

A century later the Reverend Guy Roberts of Whitefield first warned that the Old Man’s forehead was in danger of toppling. In 1916, when Edward Geddes, a Massachusetts quarry superintendent, installed the first turnbuckles, it was within four inches of falling into Franconia Notch.

Private groups like the Society for the Protection of New Hampshire Forests and New Hampshire women’s clubs helped the state legislature raise $400,000 to buy Franconia Notch and make it a state reservation in 1928. The Old Man became the official emblem of the state in 1945 and still appears on road signs and license plates. More turnbuckles were added to the Old Man in 1958, and seven years later Niels Nielsen took over as caretaker.

When he reappeared above the granite ledge, Neils’s face was flushed and his gray sideburns dripped sweat. He caught his breath. “I came up out of there, and I was wiped right out. That never happened before.” For only a moment he paused. His next words were matter of fact: “This is my last year. Dave will take over. And then Tommy.”

They stood together on top of the mountain in matching red flannel shirts with Old Man monograms — big tired Niels, a smiling young Dave, and little bespectacled Tommy — ready to carry on the tradition, ready to give the Old Man a haircut and a shave for as long as need be.

But how long will the Old Man last? It’s a question Niels can’t answer. “He could last for centuries or for a decade. We patch him up the best we can,” he said. “Of course, if he ever did start to slide, there’s not much we could do. The Lord put him here, and the Lord will take him down.”

Excerpt from “The Old Man Comes Down from the Mountain,” Yankee Magazine, July 1991.