Magazine

PoemCity | Here in New England

It sounds like the start of a joke: A man walks into a poem. Except … that’s what actually happens if he’s running errands in Montpelier, Vermont, in April—returning library books, say, or picking up some sheet music, batteries, sandpaper, a bottle of wine … stopping at the bank, then grabbing a bite to eat […]

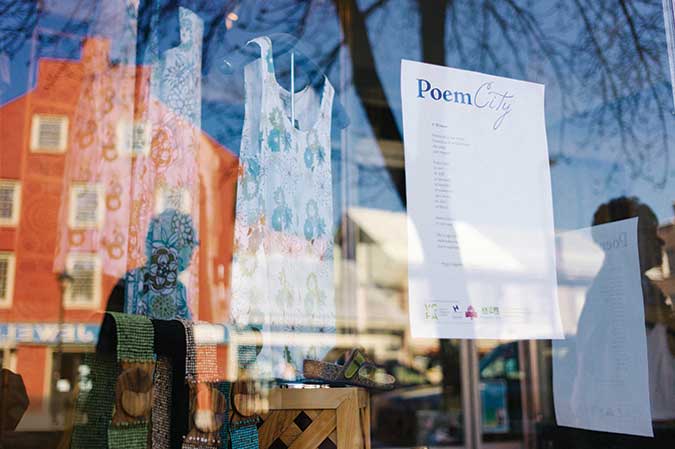

A poem takes center stage at No. 9 Boutique on Main Street in Montpelier, Vermont.

Photo Credit : Corey HendricksonIt sounds like the start of a joke: A man walks into a poem.

Except … that’s what actually happens if he’s running errands in Montpelier, Vermont, in April—returning library books, say, or picking up some sheet music, batteries, sandpaper, a bottle of wine … stopping at the bank, then grabbing a bite to eat … At every turn he meets a poem. Every store window has placards with poems. All down State Street: Salaam Boutique, Book Garden, Subway … And all up Main Street: Knitting Studio, Three Penny Taproom, Miller Sports … And down Barre Street: Salt Café, Jan’s Beauty Boutique, Vintage Trailer Supply … And along Langdon Street and Elm Street … windows of giant pages filled with poems. He can’t just bang out his errands; no, he has to pause and read each one, which takes a while, since there are more than 250 of them.

I can’t resist them, either, even though I’m in a hurry, barely noticing the gold cap of the State House gleaming through the trees like a tethered sun. I find myself glued to a poem in the window of Capitol Copy: “Anthony’s Diner,” by Diane Swan. In it a woman orders a dessert she can’t eat, when the waitress, “who never smiles, whose eyes are hard from seeing,” has somehow noticed the writer’s sadness:

and when she offers that cobblerthere is that other thing in it—she and I, part of that smallblack teepee of crowsI saw on the road this morning,all business, sharingthis beautiful, violent day.

Instinctively I put my hand on my chest as if to somehow stroke her ache. My ache? Our ache? I turn away from the window, dazed. I remember that my encounter with this poem is no accident. During the two minutes it takes me to read that poem, I become fully aware that this community of 8,000, the smallest state capital in the country, home of the Vermont College of Fine Arts and three independent bookstores, is also the civic center that for the past four years transforms into PoemCity during National Poetry Month.

This walkable anthology of verse is sponsored by Kellogg–Hubbard Library and Montpelier Alive, offering errand runners like me, and the legislators and lobbyists and bank tellers and pizza delivery people, all of us enacting our everyday routines, the chance to encounter some words, images, feelings, a voice, an insight from a poem we’d never have read otherwise. For one month, little clusters of people and lone readers pause between Guitar Sam and Aubuchon Hardware, outside Rite Aid and Bear Pond Books, on their way to the State House and the DMV, to stare intently into a window at something other than merchandise. It takes only a few moments to absorb the ideas and the rhythms of a single poem hanging at eye level, but the reverberations of that poem might follow them all the way back home and leak into their dreams that evening.

Rachel Senechal, program and development coordinator at Kellogg–Hubbard Library, brought the seed of this literary project to Montpelier from the Waterbury Public Library, where she’d helped install new poems in 10 storefront windows each week for a month. “We were hanging poems in an insurance office,” she said, “and every time we came in with a new one, they would discuss it—so we felt we were truly introducing poems to people who didn’t otherwise read poetry.” When she transferred to Kellogg–Hubbard, she wanted to continue creating chance encounters with poetry—but she wanted to present works by Vermont writers only. And when Phayvanh Luekhamhan, recently arrived from Brattleboro, reached out to the library with a desire to connect with area writers, she brought a whole Rolodex of Vermont poets to Senechal’s attention while serving as executive director of Montpelier Alive, a nonprofit charged with revitalizing the city’s arts and business community.

Luekhamhan, a poet herself, points out that PoemCity’s window-filling format is “great for poets because it’s a way to share [work] in your community without a spotlight, without the sweaty feeling of getting up and reading it in front of others. Also, a lot of people write on the side—this is an avenue (literally) for sharing their work.”

PoemCity started with 70 poets participating the first year, then 140 poets the second, and more than 250 in its third and fourth years; 2014 will be its fifth year. In that same time it’s grown from 40 to 90 business partnerships, with support now also from the Vermont College of Fine Arts and the Vermont Humanities Council. Each year a new map indicates where the poems are hanging, and a program of literary events, including readings and workshops, is scheduled to supplement the citywide show. Last year Montpelier offered 30 poetry-related programs, most of them free, on 22 different days.

“Ultimately, it’s grabbing people’s imaginations,” Senechal realizes, as she regularly hears comments such as “I didn’t read poetry before, but now I do,” and “I never wrote poetry, and now I do.” If this program is a flower, is it in bud, blooming, or in full bloom? “I think of it as an iris,” Luekhamhan answers, “blooming year after year, and all of a sudden, over time, there’s a whole garden out of one bulb.”

One day in late April, Senechal checked her e-mail and found another poem. It was a response to the whole project, written by someone who, like me and the legislators and lobbyists and bank tellers and pizza delivery people, unwittingly navigates these streets, which, for a time, have become a walkable anthology of verse. Robert Troester, a retired computer programmer and Montpelier resident of 28 years, captures the essence of his poetry-suffused community:

Now as I walk toward home to do my chores I’m pulled off track toward one storefront, then the next, A joke on one, someone’s soul on another, Craning over a shoulder to reada third, We nod at each other, “That’s a good one, that one. Yep.” Getting home takes twice the time. Now, everything looks like a poem.

Julia Shipley

Contributing editor Julia Shipley’s stories celebrate New Englanders’ enduring connection to place. Her long-form lyric essay, “Adam’s Mark,” was selected as one of the Boston Globes Best New England Books of 2014.

More by Julia Shipley