Christa McAuliffe’s Shadow | Yankee Classic

Concord Monitor reporter Bob Hohler recounts his seven months with Christa McAuliffe before the Challenger disaster in this 1986 Yankee classic.

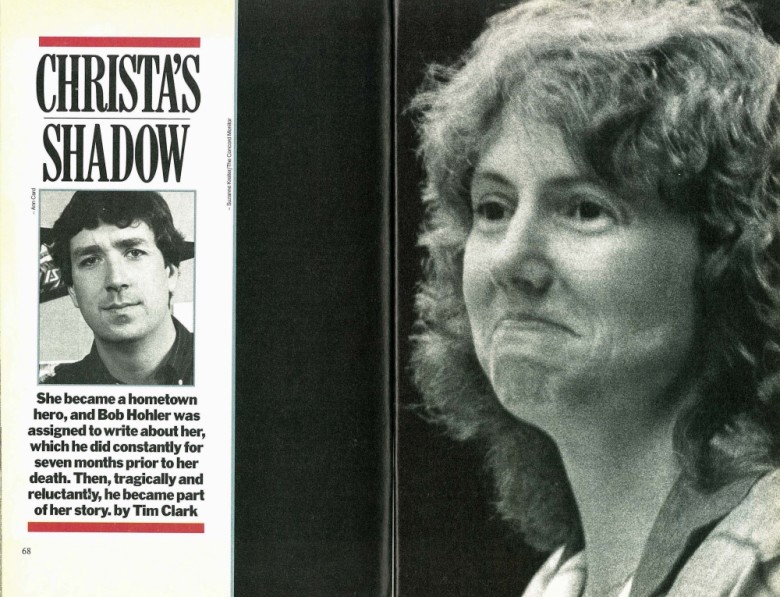

Christa McAuliffe became a hometown hero, and Bob Hohler was assigned to write about her, which he did constantly for seven months prior to her death. Then, tragically and reluctantly, he became part of her story.

After watching Christa McAuliffe’s every move for seven months, Bob Hohler had his back turned when she died. The tall, lanky columnist for her hometown newspaper, the Concord Monitor, was snapping pictures of the teacher’s mother and father when he heard what he thought was a sonic boom. Then he heard the flight announcer say, “Obviously a major malfunction.”

“All of a sudden there was a great silence,” Hohler said a month later, sitting in an editor’s office in the Monitor newsroom. “I was looking at people through my camera, watching their expressions change. Nobody was reacting quickly to it. It was a suspended moment.

“I looked around and saw the cloud,” he went on. “There were the two boosters coming out of it. I had never seen a launch, and I thought one of those must be the shuttle. It must be – nothing else came out of the cloud. Then they said the vehicle had exploded.

“I thought to myself, ‘This is incredible, unbelievable.’ But I continued to snap pictures. It was my job. I was still thinking like a reporter – a disbelieving reporter. I hadn’t accepted the fact that there was death up there. They were talking about parachutes, and I envisioned this great drama unfolding with paramedics fishing the crew out of the water. Then, after a few seconds, I realized there was something tragically wrong here.

“There were people wailing, and people on their knees praying. But still, I was thinking like a reporter. It was my natural reaction — maybe a defense mechanism. I don’t confront a lot of my emotions. I put that into my job. I remember I was rushing around, trying not to confront what had happened. The reporter for the Union-Leader, who was right next to me, started to unravel. She was sobbing and she said, ‘Will you hold me?’ At that point I did sort of well up a little. But I didn’t hold her too long. I had to dash off to do my deadline story.”

The Concord Monitor is one of the diminishing number of afternoon dailies, and Hohler had only a few minutes to write a brief report of what had happened and phone it back to New Hampshire. He finished it, called it in, then immediately called his six-year-old daughter Lauren at her elementary school in Concord. He knew she had been watching the launch along with every other schoolchild in Concord. She knew that her father had been following Christa wherever she went for a long time. He wanted to reassure her that he had not followed Christa away forever.

“Is Christa dead?” she asked him on the phone.

“It doesn’t look good,” he admitted to her.

“I really had a hard time holding myself together then,” Hohler recalled. “She sensed something was wrong, but she was excited about being called out of class to the telephone, and she was giggling about it. That helped me get through it.”

But when he finished the call, he could not relax, could not reflect on what had happened. He was surrounded by other reporters from newspapers all over the world, from television networks and radio stations. They wanted his reaction to the apparent death of the teacher from Concord. Her family and friends had been hustled away to seclusion, and of all those left in the confused aftermath of the disaster, Bob Hohler knew her best. He was no longer just another reporter on the Christa McAuliffe story. He had become part of the story.

He answered the questions as best he could. He turned down the requests to appear on TV, all except the CBS Morning News. He even lied to them, saying he was flying home that night, but they persisted. All right, he said, if he could write his follow-up story that night, and if he came to the space center the next morning to phone it in, maybe he could do five minutes on the air.

He stayed up all night writing his story, perhaps the 50th story he had written about Christa in the last seven months. There was so much to say in a short space.

Christa McAuliffe died yesterday with a few of her favorite things: her son’s stuffed frog, her daughter’s cross and chain, her grandmother’s watch, her Carly Simon tape. She died with little things. Ordinary things.

Put her by a swimming pool with her family, a bacon, lettuce and tomato sandwich, and a cold beer, and she needed little more from life. Give her a compass, her childhood friends, and a forest, and she flourished. Call her a hero, and she shuddered.

In the 200 days I knew her, Christa went from a high school classroom to a spacecraft bound for an infinite frontier in the sky. She asked to be nothing more than an ordinary person on an extraordinary mission.

How silly, she said on the day that I met her in Houston, that people would swarm her for autographs. How absolutely crazy, she said three weeks ago, that the New England Patriots would line up after a game for her signature. What a joy it would be, she imagined, to return to signing hall passes at the high school.

When I met her, I was an ordinary reporter and she was a finalist in NASA’S teacher-in-space race. I shadowed her. She had a nervous giggle and the gee-whiz bounce of a camp counselor, but she made me want to follow her. She made me wish she taught every child …

Christa McAuliffe was in Houston because she wanted to be the first teacher in space. Hohler’s presence was the end result of a series of lucky accidents, in a way. He had not started out to be a chronicler of great national stories. When he graduated from college in 1979, after ten years of mixing classes with driving cabs in Boston, he wanted to be a sportswriter. That’s what he was doing at the Monitor until the year before Christa was selected. Then the paper’s regular columnist left, and the editors decided to give Hohler a shot at the job. When Christa made the final ten, the Monitor’s regular education writer, who might have covered the Christa story normally, was on sabbatical. Editor Mike Pride asked Hohler if he would scoot down to Houston to cover the training sessions.

It was a lucky choice for all involved. Hohler has a knack for noticing details about people and for establishing rapport with his subjects. He has a relaxed, engaging personality and a fine sense of the absurd that served him well in the great solemn foofaraw that surrounded the Teacher-in-Space Program.

“In the early days, I really looked at it with humor,” he said. “All the acronyms — I thought it was funny. It was not of our world. I watched it all with a sense of delight.”

All through the training in Houston, the weightless flights in the “Vomit Comet,” the press conferences, Hohler enjoyed what he thought of as a nice story about a local woman. He knew Christa was one of the favorites to win the coveted spot, but it was hard to take it seriously until July 19, when the announcement was made at the White House.

“Only a small pool of reporters was allowed into the Roosevelt Room. I was down in the White House Press Room watching it on TV with some other reporters when, two or three minutes before the announcement, somebody came running through yelling, ‘It’s the one from New Hampshire!’ Somebody upstairs had leaked it. I had a moment of shock, then I ran for a phone to call the office in Concord. Then I remembered they were watching it on TV and felt foolish. I just wanted to tell somebody.”

She let me ride away from the White House with her after a dozen reporters had tried and failed. I sat with her an hour later when she called her husband Steven to share the news. She cried for joy, and I fidgeted, waiting for her patience with me to wear thin. It never did.

Between July and January Hohler spent almost all his time writing about Christa McAuliffe. He spent more time with her family, it seemed, than with his own. During that time he and his wife separated. “It had been building up for years,” he said. “I don’t know if I can say what effect this had on it. I’ve always been somebody who works a lot of hours. I’d told my wife before we got married that I wanted to be a sportswriter, and sportswriters travel a lot. She said she understood that. But I didn’t realize the effect it would have on my daughter. Whenever I got on the bus to go to the airport in Boston, I’d see her crying, ‘Daddy, don’t go!’ I feel a lot of guilt about that.”

I wrote about Christa for seven months, hopscotching from Concord and Houston to Florida and her hometown of Framingham, Massachusetts. My 6-year-old daughter lost me to a teachernaut.

“Christa this, Christa that,” she said. “When’s it going to be over?”

Like any good reporter, Hohler becomes involved personally with the people he writes about, even as he worries about his responsibility for exposing those people in print to strangers. During one break in the story, when Christa was incommunicado in Houston, he came back to Concord to write his normal city columns for a while. By some grim fate, one of them was on the suicide of a man he had written about earlier. “I was happy to get back to the Christa story.”

Somehow, despite the media crush, Hohler and McAuliffe crossed the line between reporter and subject and became friends. “Maybe it was because we were of the same generation,” he said. “She was 37, I’m 34. When she talked about the impact of President Kennedy on her, I felt the same thing. We’re both Democrats from Boston, we were affected by Vietnam … all through this thing, when she talked about her life, I was saying, ‘Yeah, yeah, I know.’ “

They ate together, shared their thoughts, talked about their children. “I’m as cynical as the next reporter, and I don’t start gushing over my subjects,” Hohler said. “But I felt some sort of affinity with her. It was never something we talked about, but we were friends. She would call me even when she didn’t have to call me.”

When I last talked to her 11 days ago, Christa was in quarantine in Houston and [her son] Scott was watching a Celtics game in their family room at home. She had called to say goodnight to the children and asked to say hello to me before she hung up. She was proud she had won a beer from Mission Commander Scobee when she bet on the Patriots against the Los Angeles Raiders a week earlier. And she was excited about her space flight.

“Have fun,” I told her.

“I will, ” she said.

As Hohler grew closer to Christa, his respect for her grew, too. “I knew what NASA’S motives were,” he said. “I knew they were selling the space program, and this was a great way to do it. I don’t think they could have found a better person to capture the spirit and win people over. But I never looked on her as a pawn. She went into this willingly and knew all along what she was doing. She knew the risks. She knew that she could die up there. She knew that from the beginning.”

The full moon spattered silver on the choppy waters of the Atlantic when Christa and the crew were awakened at 6:20 A.M. yesterday. The idle orbiter glittered like a space-age steeple on the skyline. A half hour later, the day dawned a pearly white. “Christa, hey, Christa!” photographers cried as she left for the launch pad at 7:50.

“We’re going to go off today, “she said, smiling, showing no trace of the frustration she displayed the day before when she climbed out of the shuttle after waiting six hours for a flight that never flew.

When she reached the sterile room that leads to the shuttle, a technician gave her a shiny Red Delicious apple. She joked with astronaut Judy Resnik for a while, shook hands with the ground crew, and crawled on board.

“Good morning, Christa,” said a controller, testing her headset at 8:35 A.M. “Have a good day.”

“Good morning,” she said. “You too.”

“They were her last public words.

The morning after the catastrophe, after a night with no sleep, a stretch limousine picked up Hohler to take him to the television show. He struggled through the five-minute interview — like many reporters, he finds being interviewed a harrowing experience — filed his story, and flew back to Concord. The city was in a state of shock and mourning, and the world wanted to hear and read about it. His colleagues on the Monitor were trying to cover the story thoroughly, even as they struggled with their own grief and the conflict between the demands of their profession and their reluctance to intrude on the sorrow of their neighbors.

Hohler felt that conflict most of all. He was suddenly in demand. People wanted to interview him in California, in Germany. He could write stories for almost anyone for a lot of money. He could write a book. He was a celebrity, and he was mixed up.

“I felt some sort of obligation to tell people what I knew about her, who she was, what she meant to people,” he said. “But I felt real uncomfortable about capitalizing on the death of a friend. I said no to a lot of people.”

Still refusing to confront his own tangled emotions, Hohler flew to Houston to write his last Christa column on the memorial service at the Johnson Space Center. It was a way of closing the circle for him. He had met her there, and this would be his chance to say farewell. His instinct for the telling detail did not fail him.

Cymbals crashed, and a bass drum rolled like thunder, but Staff Sgt. Susan Arnold’s silver trumpet went silent yesterday as a nation’s grief grabbed her by the throat.

Her cheeks wet with tears, Arnold stopped in mid-stanza as her 539th Air Force Band played “God Bless America” for the families of the seven men and women who left the Johnson Space Center last week on a journey that ended too soon in the sky above Florida.

“The air was so full of sorrow,” she said, “so full of anguish. I had no music left inside me.”

“It was a very emotional service,” he said on a bright day in February in Concord, where people were trying to live their ordinary lives again. “I saw all the teachers that I met in Houston in the beginning. Seeing the Kennedy kids there brought back the Kennedy assassination. Mike Smith’s daughter with her teddy bear, and the jets flying overhead … I went back to my hotel room to write the story, and on the TV they were playing it again and again. I started sobbing, and it all came out. It was good to let it out. But I’m not ready to stop writing about it.”

He has reconciled himself to writing a book and to the chance that some may accuse him of taking advantage of a friend’s death. He feels good about doing the book for personal reasons, for professional reasons, “and, pompous as it may sound, for historical reasons. Because I was close to it and went through it. I felt thrust into this thing that I never expected to happen. I want to do something sort of inspirational and upbeat.”

If he is criticized for his ambition, so be it. He learned something about ambition from Christa. “She was very ambitious in a personal sort of way. She didn’t want to be a hero — she didn’t need that fame and glory stuff. But personally, when she set out to do something, she was determined to do it the best way she knew how. I think she would have been very disappointed if she hadn’t been chosen. She would have been hurt because she had put so much of herself into it.”

He is not ready to let go of the Christa McAuliffe story, nor has it let go of him. “It’s made me see how fragile life is,” he said. “I just had a friend who went away for the weekend, and he didn’t come back to work yesterday. I spent the whole day wondering if he was dead by the side of the road somewhere. Turned out he was home sick, but it really hit me.”

His daughter has asked him for God’s telephone number so she can call and tell Him to send Christa back. And Bob Hohler still finds it hard sometimes to look at the sky. “When I see clouds,” he said, “I see that cloud.”

Excerpt from “Christa’s Shadow,” Yankee Magazine, June 1986.

READ MORE:Christa McAuliffe’s Messenger | Interview with Grace Corrigan McAuliffe