The Yankee Interview | Jennifer Miller Field

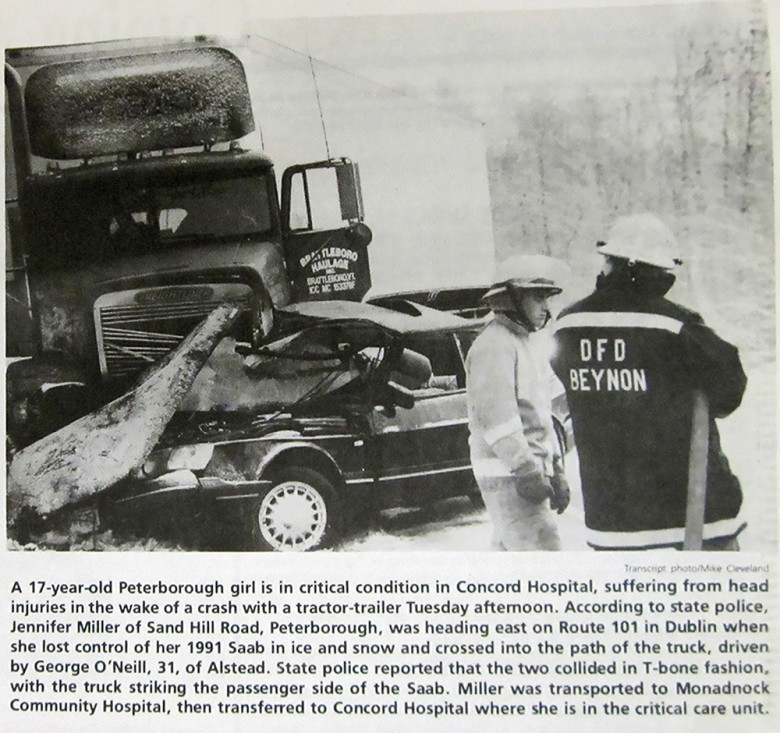

On November 17, 1992, 17-year-old Jennifer Field was driving home from school in Dublin, New Hampshire. An accident would then change her life forever.

Jennifer Miller Field

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Jennifer Miller Field

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Jennifer Miller Field

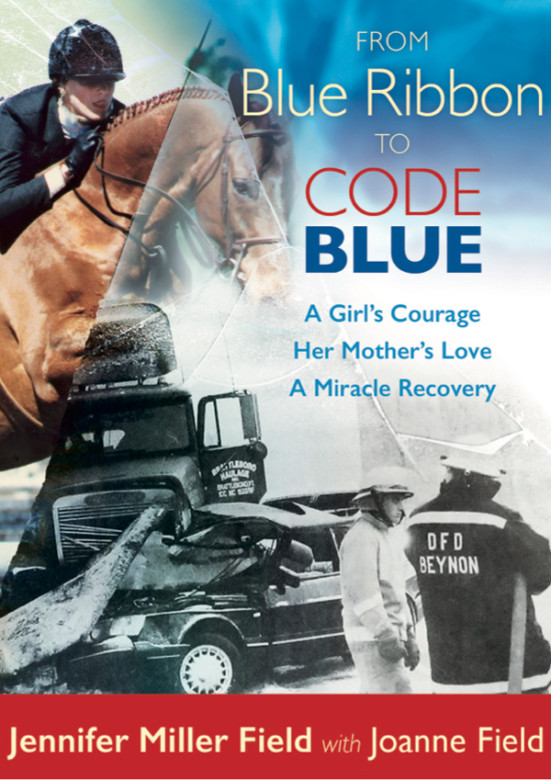

On November 17, 1992, 17-year-old Jennifer Field was driving home from school in Dublin, New Hampshire. Humming along to a Queen song, she was looking forward to having her boyfriend over later that night, her mind occupied with deciding what pair of jeans to wear.Freezing rain was falling when her Saab hit black ice. Field lost control and the car collided head-on with an oncoming tractor-trailer. She suffered a traumatic brain injury (TBI) that left her paralyzed and comatose for two months. Doctors told her mother she would never walk or talk again. But for Field, such a grim prognosis wasn’t an option. At the time of the accident, Field was a top competitor in the equestrian world with her eyes set on the Olympics. Her unfailing optimism and drive would guide her through a miraculous recovery. Jen, as friends and family call her, is down to earth yet introspective. In 2016 she published her book, FromBlue Ribbon to Code Blue: A Girl’s Courage, Her Mother’s Love, A Miracle Recovery. She’s the president and creator of the J. Field Foundation, dedicated to helping individuals affected by severe head injuries. In January, she attended the All American Inaugural Ball in Washington as a recipient of the prestigious Hero Award. Recently engaged, Field splits her time between New Hampshire and Santa Monica, California. We caught up with her to talk about angels, poetry, and the many forms hope can take.

It’s evident that you were particularly ambitious as a young person. Was this a result of the two strong women in your life; your mother, Joanne Field, and grandmother, Joanne Bass Field Bross? How did those two role models impact your focus on horseback riding and then later, on recovery?

I definitely think ambition was in me, inherited from my grandmother, and from my mother, too. But for me, my recovery was making it into a competition. I wanted to win, which is how it was all through my riding. I looked up so much to my grandmother and my mother, who were forces. But in my mind, recovering from my accident was just a reenactment of a horse competition.

You and your mother have a close bond. Can you talk about your mother-daughter dynamic and how it might be unusual? Do you think the accident forever changed the way you interact?

I’m 41 and I talk to my mother every day. We’ve always been very close and we have a very special relationship. I attribute a lot of our special bond to the accident. I’ve lived two lives. I was about to break away from my mother and go away to college. But instead of breaking away and doing my own thing, I had this accident. In a sense, I was forced backwards and closer to her. I was put back in the womb. I had to start again as a child, as a baby. It was difficult for both of us. When I was a teenager, the riding brought us together. She went with me to every horse show. This bond transferred from the riding world to the recovery world. She was riding Mom and later recovery Mom. But when I did go away to college, once my mother got over the fact that I was gone, she was excited. She wasn’t held back anymore by my recovery. She could be herself again. Everyone thought she would be devastated when I left. Her reaction was actually to the contrary. But she always worries about me. She’s always a mother.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Jennifer Miller Field

Seeking the use of psychics, healers, and bodywork—your mother was ahead of her time in thinking about alternative medicine. How do you think your recovery would’ve been different if she hadn’t been so open-minded regarding these practices?

I think it was a godsend. It was out of the norm back then. Even today people don’t recover like I did. Don’t forget, back then we didn’t have the Internet. We didn’t have Google. People tell you, ‘There is no way. You can’t do anything about this.’ Well, we believe there is always something. There is always another approach, another angle or pathway. You just have to be determined. And mom was always on the phone to find these options and methods. I would not be where I am today if we hadn’t believed giving up was never an option. Nobody thought I would be anywhere close to where I am now. But with a positive attitude and the willingness to change direction, no one can ever tell me, ‘That’s it.’

Was there any particular moment you recall as a turning point in your recovery? Is there a specific memory you can point to in thinking: I can do this?

My first memory was waking up in a blue padded room. I was lying in bed, turned toward the wall, thinking, what’s happened to me? But then I looked at everything step by step: getting out of bed, getting in my wheelchair, trying to wash my face. I wasn’t able to think like I am now. I wasn’t able to comprehend what was going on, where I was. There was just something in me that knew I had to work, because that’s all I’ve known. My whole focus in the beginning was to become who I was, to be a rider, to go back to exactly who I was. It took me a long time to realize that would never happen

What was it like to come to terms with realizing you’d never be the same Jen Field you were before the accident?

I wish I could skip or hop or run as well as I used to. I wish I could drive a car. But those things are small in comparison to the transformational occurrence I’ve lived through. At 17 years old I matured so many years. And when I realized I wouldn’t be a rider anymore and embraced the new me, that transition was incredibly profound. When I let go of the old Jen, in a sense, my recovery became easier. In the beginning everyone said to me, ‘You have to accept your accident.’ I was thinking, how can I ever accept this? But when I finally did accept my accident, I realized what I’d been given was a gift. I’ve become someone else. I’ve been able to live two lives.

You have an amazing and perhaps unusually positive perspective on your accident. Do you have any advice for people who feel bitter or angry when tragedy occurs?

People do get bitter. I believe there’s good that comes out of anything. There are so many good things and positive things that have come out of my accident. But if you don’t have your eyes open to it, you won’t see it, or feel it. Being bitter keeps you in the same place. I’ve never been bitter. I’ve hardly ever been depressed. Someone recovering needs to be open enough to see the good. No, I can’t ride ever again. But I can speak. I can write poetry. I can perform the keynote speech all over the country.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Jennifer Miller Field

You’ve created a one-woman show about your accident and recovery called A Distant Memory, and of performing, you write, “I feel that a little piece of my trauma drops away.” Do you think the creative process of acting could be healing to other survivors of trauma?

I don’t know if acting in general would do it. For me, it doesn’t matter whether you speak it, or write it. Acting helped me to speak through my voice. What really matters is talking about your recovery. A lot of people want to forget about their injury. It took me awhile, but now I’m really proud of what I’ve done. I’m really proud to be where I am. But that process took a long time. A long time.

Horseback riding was a huge part of your childhood and at several points you tried to ride again. What is your relationship with horses now? What do you remember loving most about the sport? Are you able to find adrenalin rushes anywhere else in your current life?

When I performed my one-woman show for the first time at the Ruskin Group Theatre [in Santa Monica, California], I walked off stage and said, “I found it again, that feeling I had when I went into the ring for the first time.” My body is always searching for that. I’m not involved with horses at all. Maybe this is a bit selfish, but I just can’t do it. I loved the competition; I loved the adrenalin and winning. I know it’s been 24 years, but I’m not ready. For me, the love was so much about competition. And being around horses, being in that environment brings back the realization that I can’t ride anymore.

Over the years so many people contributed to your recovery, from your caretaker to eye surgeons and yoga instructors. What did you learn about human connection through this process?

I think that the fact that I’m so grateful has contributed to people wanting to work with me. People saw my inherent need and want to work and do well, which in turn made them want to help more. When someone recovering is just there, and not doing much, and doesn’t care, you don’t want to help. We went to Chicago to learn exercises and then we would come home and do them constantly. So after a few weeks, my mother called The Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago and said, ‘Ok, she can do them now, what next?’ And they didn’t believe us. They didn’t believe I could already do the exercises on my own. I think people responded to me wanting to get better, and my willingness to do anything. It just didn’t matter what you told me to do. If you told me to stand on my head and juggle, then I would figure out a way.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Jennifer Miller Field

Your book is unique in that it’s a dialogue between you and your mother, but also between you and the community of people who impacted your recovery. How did you decide to structure your book?

I wanted to make the book enjoyable to read, like a novel. When I started writing, I wanted my mother’s opinion. She was so much a part of my recovery. I never could have done it without it her. I needed her help to write the book because there was so much I didn’t remember or I wasn’t aware of. I needed her voice. And I’m just so grateful to all the people who helped me along the way, so I wanted their voices in my book, too. You don’t just recover on your own. You have to do it with a team. I didn’t feel it was right for me to just write a book about my recovery, because there were so many people who were a part of the process.

Do you believe all physical impairments are surmountable with enough hard work?

I believe you can achieve almost anything if you push through. Some people said to me, ‘You were just lucky.’ Do I believe that? Maybe. But there’s a lot of work that goes along with the luck. I wasn’t lucky to get into the accident. I had a pretty severe head injury. It takes a lot of determination. If you fall down, get back up. You can’t give up. You have to stay the course.

Kelsey Liebenson-Morse

Kelsey Liebenson-Morse was born in Wisconsin, and spent part of her childhood in Florida, but considers New England home. Kelsey prefers to be outside and still re-reads the Harry Potter Series occasionally. She can often be spotted riding her bike or running. She believes herself to be the only ‘Kelsey Ananda Liebenson-Morse’ in the world, but has no way to prove it.

More by Kelsey Liebenson-Morse