Wil Smith’s Fast Break | Yankee Classic

In over 40 years of writing about New Englanders, Yankee editor Mel Allen calls the story of Wil Smith and his daughter Olivia the most inspirational.

Wil Smith’s Fast Break | December 2000

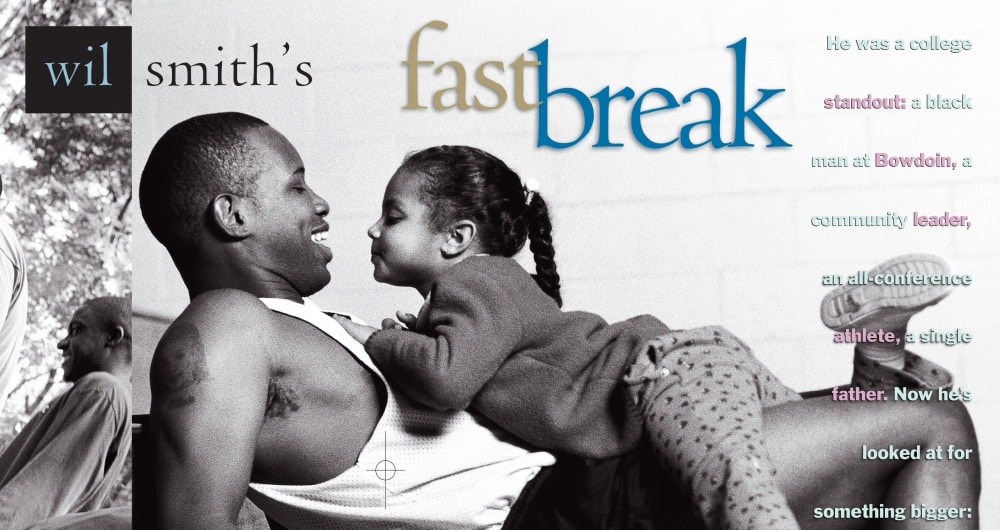

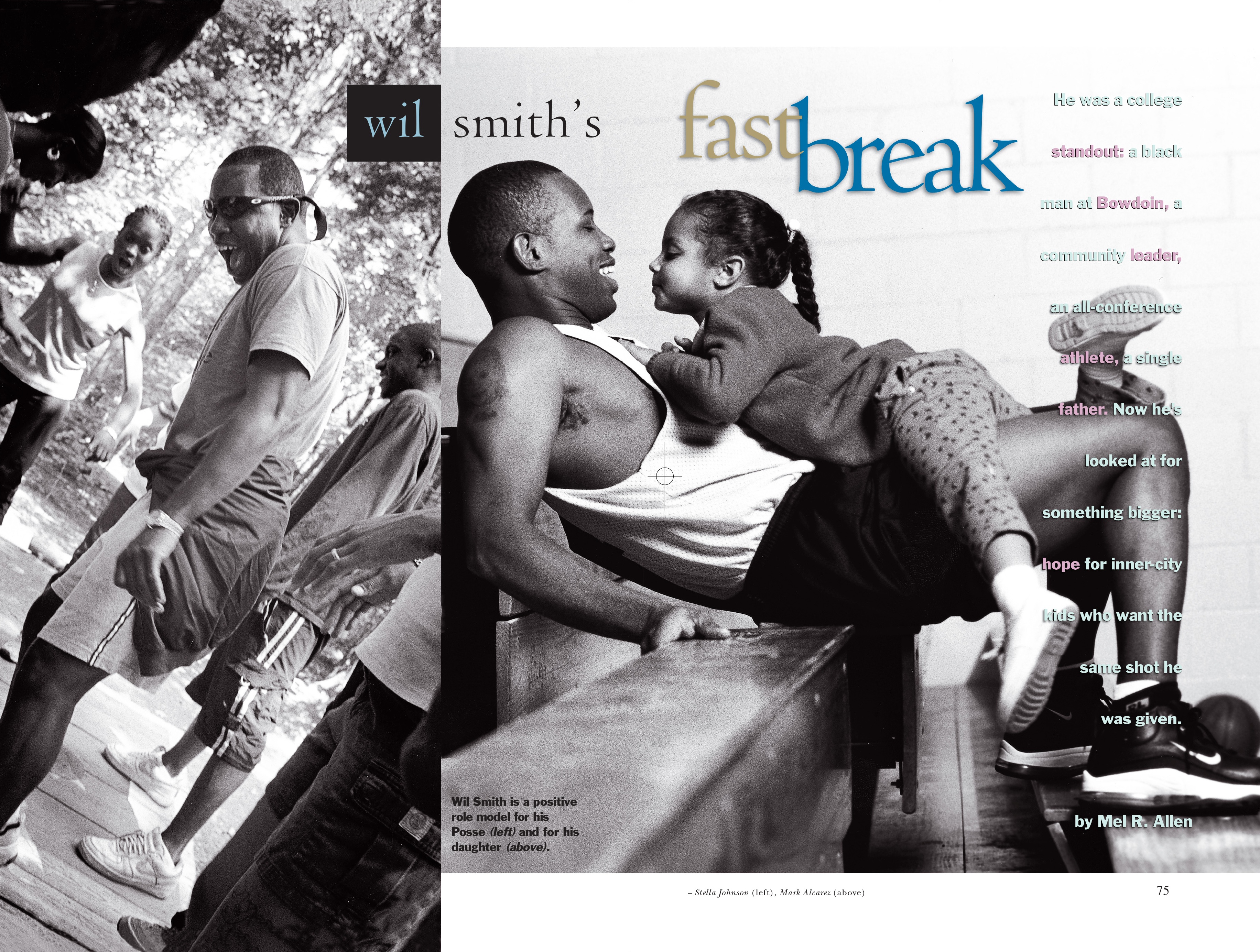

Photo Credit : Stella Johnson (left) Mark Alcarez (right)

First published in Yankee, December 2000.

All those nights when Wil Smith stayed awake because his baby daughter’s asthma flared up and she was coughing hour after hour, he’d hold her, rock her, until she’d sleep, and he’d keep reading his textbook until finally he, too, dozed off. He was simply a single father, trying to get through Bowdoin College, carving time between being captain of the basketball team, studying, and caring for Olivia. He was doing his best to make a future for the two of them. But he never thought he was on a mission. He was unique at Bowdoin — the school’s first single father, a seven-year Navy veteran ten years older than his classmates. He was the product of an inner-city high school attending a college in Brunswick, Maine, where more than half the students arrived from prep schools. He was one of fewer than 40 African-Americans in a student body of 1,600. He was, in the words of Dean Craig McEwen, “Bowdoin’s most remarkable student in memory.” Instead, the mission chose him. Over the past four years, Wil Smith’s extraordinary struggle to succeed galvanized a campus. He challenged his classmates to question what they were being taught. It may be the truth, he’d tell them, but only for the upper classes — not for the people he had grown up with. He forced professors to check their assumptions, their points of view. He started a program for Bowdoin athletes to volunteer in local schools. He showed the administration that when it gave a chance to a high-risk student, that student could give back double. After seeing what Wil Smith gave, Bowdoin wanted more students of different races, different backgrounds. Different voices in the classroom. Bowdoin wanted more Wil Smiths. How to find them was one problem. How to help them succeed was another. Will Smith’s giving was not over.* * *

This fall Eider Gordillo entered Bowdoin on a full-tuition scholarship. So did Eliztaicha Marrero, Danielle Sommer, Marie Jo Felix, and six others from Boston’s urban public and parochial schools. They form Bowdoin’s — and Boston’s — first Posse, a program that sends inner-city students to some of the country’s most prestigious colleges. The Posse Foundation started in New York City in 1989. At that time, city kids were typically going off to colleges full of hope, only to return defeated and bewildered. “If I’d had my posse with me, it’d have been easier,” they said. The Posse Program identifies students of ability or promise who often are overlooked by colleges like Bowdoin. The Boston Posse met weekly for seven months, preparing to enter Bowdoin not just to succeed in the classroom, but to be leaders. Wil Smith is the Bowdoin Posse mentor. “When I met these kids,” he says, “I thought, ‘Wow, is Bowdoin ready for this?’ These are mentally tough, dynamic kids who will stand up in the classroom and express their experiences. They are going to shake things up. They’re not necessarily poor, but they have all overcome obstacles. A lot of my friends have taken courses on poverty, but they’ve never seen it. They go right from Bowdoin to Wall Street. They make decisions that will affect people, but they don’t know about life except from books.” Eider Gordillo dropped out of East Boston High at the age of 16. Before returning to school, he spent his days playing chess in Harvard Square. Besides being a brilliant musician, he is street-smart and confident. “I’ll be able to bring a perspective to Bowdoin they may not want,” he says. “The values of a rich white kid are different from mine.” But he knows Wil Smith will be there for him. “Wil’s been through what we’re going to go through,” Eider says. Eliztaicha Marrero lives with her grandmother in East Boston. Her mother died in the past year, and she has only recently met her father. She’s afraid she’ll be hopelessly homesick. “Wil makes me believe I can do it,” she says. “If he can make it, there’s no way I should complain.” Marie Jo Felix was valedictorian at South Boston High School. She feels “not prepared” for Bowdoin, but says, “If I get down, I’m just going to think about Wil and what he went through to get where he is.” “I try and educate people about the people I come from,” Wil says. “The story has to be told about the people I come from.”* * *

Wil’s story begins far from Bowdoin, in the lower-working-class northwest section of Jacksonville, Florida. “I remember going to school when a successful day for teacher was just getting home,” he says. “When parents were just concerned with getting food on the table.” Mildred Coleman had seven children of her own, and three with Wilbur Smith Sr., Wil’s father. “My father worked all the time,” Wil says. “My mother did the mothering and fathering.” A longshoreman for 40 years, Wil’s father left Wil’s mother when Wil was young. “My mother was the most incredible person I ever met,” Wil says. He was the last of ten children she raised. Wil’s siblings still tease him that he was her baby. But there was a reason. At age eight, Wil had open-heart surgery to correct a defective valve. Mildred worked every day as a nursing-home dietician and still found time to coach boys’ and girls’ baseball and basketball. “My mother always put us first,” says Wil. “A lot of what I do today, I just want her to be proud of me.” She cared enough so that when she laid down a rule, it stuck. “I hated losing so bad,” Wil remembers. “I cried and threw a fit. She told me if I ever cried again, I’d never play. At one game we were losing and I felt a tear. I looked up and caught mom’s eye. I felt that tear go right back up. I never shed another tear at a game. “She dragged my big brother Michael right off the football field. He was always getting into fights and she told him: No more. This one game a fight broke out. She was working in the concession stand and she ran out on the football field, holding a ladle, and she pulled players apart. She took Michael right off. He was the team’s best player, and he never played high school football again.” Everyone in northwest Jacksonville knew the Smith boys because they were athletes. Wil’s brother Otis, four years older, was tall and rangy, a natural on the basketball court. When they weren’t in school, Wil and Otis played ball. When Wil stopped growing, he stood 5’10”, the smallest of all the Smith boys, but he was fast and tough and nobody worked harder. He wanted to play on his mother’s teams, but she said no, she wanted her children exposed to the best competition. She put Wil and Otis on buses or in taxis to play for coaches in other parts of the city, coaches who knew the sport better than she did. Wil played sports year-round. He was an all-star in football, basketball, and baseball. As a sophomore, he became the starting quarterback for N.B. Forrest High School. His brother Otis, who went on to play seven years in the NBA, had just graduated after setting school records there in basketball — records that still stand — for rebounds, scoring, and blocked shots. “But Wil was never just my little brother,” says Otis. “He was good enough so people knew him for himself. He was loved for being himself.” Mildred never missed a game. She learned how to drive at age 45, just so she could watch them. She had all these kids playing something, and sometimes she had to leave in the middle of one game in order to catch the end of another. Then she got cancer. She died on November 27, 1983, on Wil’s 15th birthday. “They sang ‘Happy Birthday’ to me in her room at hospice. Mother tried to open her eyes. When the song was finished, she died. I always keep that with me. She knew we were there.” Wil tried to lose his grief in sports, but the fire was gone. He kept looking for Mildred, and she wasn’t there. “My mother was my biggest fan,” he says. “When she passed away, it was like, ‘Why am I still playing?’ A lot of my joy in sports came from my mother’s look.” Wil struggled to cope. He still played, and his talent carried him to all-conference honors in three sports. But he was drifting. “I never reached the heights everyone thought I would,” Wil says. When colleges sent recruiting letters, he didn’t bother to respond. Reluctantly he attended Florida A&M in Tallahassee. He played one season of winter baseball, but his heart wasn’t in it. His father, who had remained close to Wil, told him he didn’t have the money to help with tuition. “My father broke down and cried telling me,” says Wil.“I’d never seen him cry. I saw the hurt in his eyes.” After a year and a half, Wil left school. He then did what many young black men did when they were without direction in Jacksonville: He hung out with other young men and flirted with trouble. He describes it simply as “a rough crowd.” He felt like a failure and found refuge with others whom society had judged as failures, too. His siblings drew away, unable to watch him ruin his life. “I didn’t have to get in shoot-outs or do drugs or stickups,” Wil says. “I was the brains. Mix street sense with brains and you have a dangerous person. There’s a friend of mine, he killed two people, he’s been in jail ever since. I always use that as a reminder of what direction I could have gone. “I’ll never forget this,” Wil says. “I was at a store and the Sports Channel came on with a baseball highlight. A guy said to me, ‘Wil, man, you’re different. I expected to see you up there, playing ball on TV.’ I witnessed pretty heavy stuff. But there’s no way to get away from good roots. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t rest. I knew I wasn’t supposed to be there. My middle brother is my rock. He was on the streets. He knew. He took me for a ride in his car. He said, ‘What are you going to do? Your sisters are going crazy. They are worried sick.’ He never judged me. He never said what I was doing was wrong. That’s what I needed. I didn’t need someone pointing his finger at me. I did that to myself.” The turning point came in the winter of 1989. Wil was pulled over by the police, and a rifle was found beneath his seat. He had no driver’s license. The judge took into consideration the fact that Wil had no prior record. “I should lock you up,” she said. Instead she told him to join the military. He called the Navy recruiter from the courtroom lobby and left the following day. “I wrote a letter to my family from boot camp,” Wil says. “I thanked them for being so tough. They had made it clear: They wouldn’t support me being on the streets.” Wil trained to be an aviation electronics technician, specializing in land-based antisubmarine aircraft. He flew ten-hour missions. He was in the air nearly every other day for five years. He got married, then divorced. He served in the Gulf War. In December of 1990, while stationed in California, he received orders sending him to Italy to join a squadron based at the Naval Air Station in Brunswick. “I was happy,” he says. “I thought it was Brunswick, Georgia, near my family in Jacksonville. I’d never heard of Brunswick, Maine.” In Maine people still glance with curiosity at a black man walking down the street. “Kids at Bowdoin see a police car and think, ‘I’m safe,’” says Wil. “I see a police car and think, ‘trouble.’” One night he was driving back to the Navy base with his two nephews in the car. He had brought them to live with him so they could attend Brunswick High, a place he knew would give them a better chance to succeed in college. Three squad cars of base policemen pulled him over. “They were looking for a black man driving a blue Camaro who had stolen a car,” Wil remembers. “I was driving a white Firebird and showed four different forms of ID. Still they refused to believe me. They were trying to make me say I was someone else.” Each day at the base when Wil finished work he’d head to the gym for pickup basketball, but he wanted to do more with his time. “I’m best as a human being when I have others besides myself to focus on,” he says. He saw an ad in the local newspaper for a volunteer football coach at Brunswick Middle School. Wil was the only applicant, and he got the job. “I was 22 years old,” Wil says. “I had 60 white kids on my team. Most of them had never been in contact with a black man. I had no problem with the kids, but it wasn’t an easy adjustment for the parents. They asked for a meeting with me. They said I was too intense, they didn’t think their kids were ready for it. I told them that every day after practice I’d ask the kids, ‘Anybody hurt? Anybody not having fun?’ The kids always said they were fine. I told the parents, ‘I’d like you to be on my side, but as long as your kids are with me, they’re mine for three hours a day.’” By the end of the season, some of those same parents would phone Wil telling him their kids were slipping in their schoolwork, would he come talk with them? Wil became a community fixture, coaching basketball as well as football. His teams played hard, and they won. During the summer of 1995, while he was coaching at a basketball camp, Wil’s ability and character caught the eye of Tom Gilbride, Bowdoin’s men’s basketball coach. Coach Gilbride asked Wil if he had considered college. Would he like to apply to Bowdoin? Wil was at a professional and personal crossroads. He had served seven years in the Navy and was due to re-enlist. But the Navy meant six months overseas every year, and by then he was a father. He’d met Olivia’s mother in Portland after returning from overseas duty. She gave birth in May of 1995. The relationship broke up and the baby lived with the mother, but Wil got Olivia every Thursday and kept her until Monday. “No matter how untimely, Olivia didn’t ask to be here,” Wil says. “It wasn’t a question of flight. I can’t imagine a life without her.” Wil then left for a six-month overseas assignment to Sicily. It was there that he decided he would go to college. He sent a hastily written application to Bowdoin, and Bowdoin took a chance. His last day of active duty was April 25, 1996, the same day Olivia’s mother gave Wil full custody of his 11-month-old daughter because she didn’t feel she could raise her. “There are plenty of mothers who would keep the child to spite the father,” says Wil. “It’s courageous to say I can’t.” He watched mothers with their daughters. He learned how to braid Olivia’s hair.“ I took a lot of pride in her personal appearance. No matter what was going on, I wanted her to look nice.” He had a portrait of Olivia tatooed on his right shoulder. Though Wil had been accepted at Bowdoin, he remained in the Naval reserves to pay his bills. He didn’t know how to apply for student aid or room and board. When he started college in September 1996, Olivia was 15 months old, and he had no choice but to bring her to class with him. The professors soon learned that when Olivia was sick, Wil would not be able to come. The money he saved from the Navy went faster than he could have imagined. Sometimes he didn’t eat for two or three days so he could feed Olivia. Then basketball season started. “Coach didn’t know,” Wil says, “but I lost 17 pounds. I couldn’t sleep. I got an F in a course — Latin-American Studies — that required you to read about 20 books. I didn’t have money for the books, and I didn’t know they were on reserve in the library. I said to myself, ‘I can’t make it. This is just too hard.’ ” He told his adviser simply, “Things are hard for me right now.” The adviser called Betty Trout-Kelly, the assistant to the president of Multicultural Affairs and Affirmative Action for Bowdoin. On a Sunday afternoon late in Wil’s first semester, Betty Trout-Kelly sat him down and told him, “I know you feel you shouldn’t need this support system, but if you don’t take the help we can offer, it will be your fault. And if you don’t accept it, you won’t make it.” For the first time Wil told her about his struggles. “The struggle to survive was so great,” says Trout-Kelly, “that he couldn’t be a student.” She called meetings — the development office, the dean of student affairs, and the president of the board came. Trout-Kelly and Dean Tim Foster telephoned Wil after the meetings. A fund from an anonymous donor would give $25,000 for Olivia’s day care. Wil would be able to move to campus housing and eat regularly with his daughter at the school. Trout-Kelly said to Wil, “I know you can do well at Bowdoin. You’ll have an opportunity to prove yourself.” Wil replied, “Thank you. I’ll prove myself worthy.”* * *

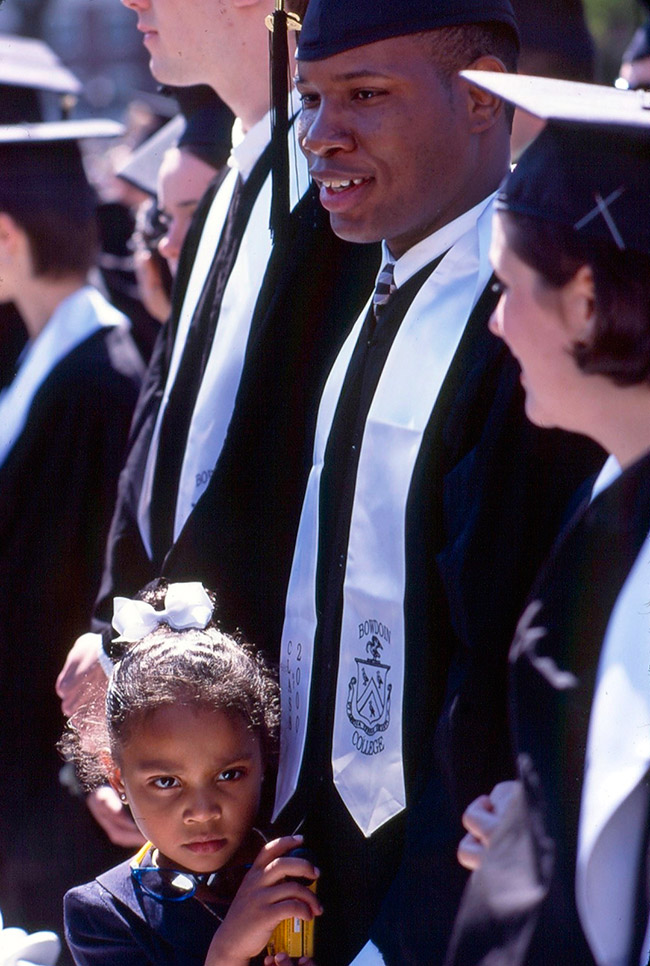

Spend a few hours at Bowdoin and you can’t miss Olivia Smith. She’s the bouncy, pretty five-year-old girl with braided pigtails and happy brown eyes that everyone is picking up and fussing over. Coach Gilbride was so used to her presence during practice that he’d often swoop her up and direct the practice with her snuggled in his arms. Once he gave Olivia his set of keys to play with during a practice. She ran off happily, and the keys haven’t been seen since. During Bowdoin’s games she roamed the stands, and it seemed as if the whole world knew her name. Wil played with his head on a swivel, always looking to find her during breaks in the action. Wil calls his daughter “my complex joy.” He says, “If it was just me with the academic background I had coming to Bowdoin, I’d never have made it. All those nights when I was so tired, I was ready to quit on papers. But then I looked in on Olivia sleeping, and I turned right around and went back to my paper. She put life in perspective for me. When she was two, I was walking her to school. It was cold, and I was holding her hand. My mind was in turmoil. I had midterms; my car had broken down; we had no money. Olivia was talking about leaves and trees. I didn’t even realize she had let go of my hand. I had taken another ten steps without her when suddenly I turned. She said, ‘Dad, talk to me.’ She was saying in her own way, ‘Look, none of this other stuff matters.’ All she cared about was that we were there. She was glad the car had broken down. That meant we could walk to school together.” Wil became a four-year starter on a nationally ranked team at an age when other men are playing weekly pickup games at the YMCA. He made the conference all-defensive team. He was like a coach on the floor, challenging his teammates to play harder. “These aren’t tough kids,” he says.“ You can’t give toughness to them, but intensity can rub off.” Wil became a well-known advocate for diversity throughout Maine. He worked with civil rights teams at local high schools, prodding educators to find leaders in places they never looked. He attended conferences on multiculturalism with the governor. He got Bowdoin’s athletes to volunteer at rural schools. He worked summers as a counselor at Seeds of Peace International Camp in Otisfield, Maine, where Israeli and Palestinian kids live together. Last May 27, beneath a sparkling blue sky, Bowdoin held its graduation. Slowly Robert H. Edwards, Bowdoin’s president, read off the names of its more than 300 graduates. When he said, “Wil and Olivia Smith,” Wil carried Olivia in her shining blue dress to the stage. There was a great roar, and everyone — students, faculty, and parents — stood and cheered.

Photo Credit : Dean Abramson

Learn More About Wil Smith:

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen