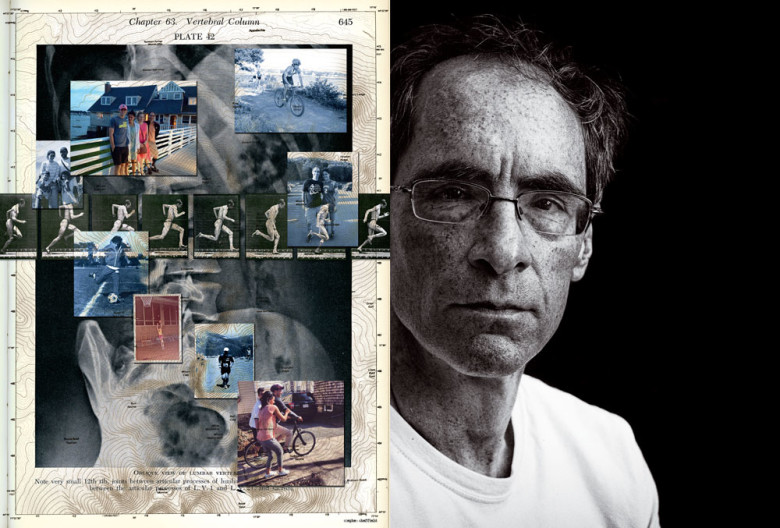

The Way Back

When an athlete and adventurer can no longer even stand up, what can he do? A memoir of fatherhood, losing hope, and finding it again from Todd Balf.

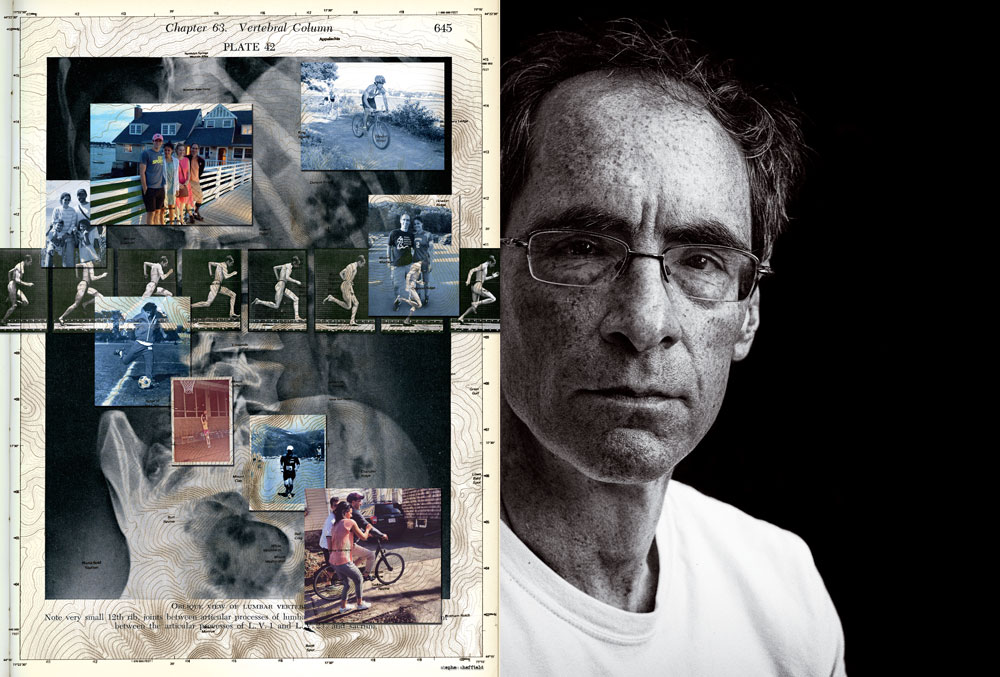

The day I was diagnosed with a rare spine cancer, a part of me almost felt relief. For months, I’d been suffering from debilitating nerve pain. I’d stopped running and mountain biking when the jarring got to be too much on my lower back. I couldn’t lift weights anymore. What I was down to in summer 2014 was a road bike on smooth pavement. I told friends I likely had a herniated disc—every 50-year-old I knew had some sort of lower back ailment—and that I didn’t plan to see a doctor as long as I could ride something somewhere.

As the family story goes, I taught myself to ride a bicycle as a 3-year-old, overcoming the problem of legs not reaching the pedals by sitting on the rear fender. I’ve been running and biking and pushing ever since. As an outdoors adventure writer I’ve climbed the iconic Grand Teton in Wyoming, biked the length of Israel along its version of the Appalachian Trail, tramped across the fabulously lethal Darien Jungle in Panama, and braved big Maine rivers in early spring to become a whitewater guide.

I imagined my cancer comeback to be no less energetic. I joked that my disease, called chordoma with only 300 cases a year in the country, was proof of what I’d always maintained: I was one in a million. I rode a bike across the city to my pre-surgery radiation appointments and pumped away on a YMCA exercise bike before each of the 28 sessions. I charted my minutes and the levels I rode at, and noted approvingly that I was somehow trending stronger even as a continent-shaped burn mark—a silhouette of the tumor inside me—darkened my lower back in the last week.

I was as mentally and physically robust as a man carrying a tumor inside his spine might be. I looked forward to the massive surgeries to come, when Boston’s best doctors would excise the grapefruit-sized mass, at which point I’d get back to being me again.

Here’s the moment when I first realized that I wouldn’t be me again: I was on the edge of the hospital bed with a nurse and physical therapist on either side to help me to my feet for the first time. It was only a few days after back-to-back, eight- and 10-hour-plus surgeries. The first had cut me open from the back to lay in the supporting hardware for a transplanted fibula—my new backbone. The second, even-longer surgery had gone in from the front to saw free the vertebral tumor. The surgical team told my family their work had gone well and that rehab should begin immediately.

“Can we let go?” the nurse and therapist wanted to know. Of course they could let go. Standing? What could be more rudimentary to a guy who in the past decade had twice raced to the top of Mount Washington, once on foot and once by bike? I smiled confidently as they pulled their hands away. But there was a void in the place where my legs should have been. They were there, but they weren’t. I began falling.

—

I can’t recall when my children first came to visit at the hospital, but it wasn’t for several more days. This wasn’t an oversight. I told my wife, Patty, I’d like them to stay away. If it sounds like I was protecting them, that’s only partially true. I wanted to buy myself a few days and put things in the right. I wasn’t expecting to be in the hospital long. They’d see me at home, not much the worse for wear and gaining.

At the time of my diagnosis, Patty and I were quasi-empty nesters with both children in college. Henry was a freshman just getting started at Boston College. He’d been off everyone’s recruiting radar when all his work and talent and love somehow totaled up and drew the interest of multiple D1 soccer programs. BC was a dream come true for him.

Our oldest, Celia, was entering her junior year. She was doing well, but anxious about the future and fighting back onto the field after a second ACL knee injury. Her grit had earned her the co-captaincy of the UAlbany soccer team.

I’d also torn up my knee, as had my college athlete brothers. As a youngster, Celia sometimes alluded to a catastrophic knee blow-out as fate. She was a beautiful runner whose stride was long and effortlessly explosive. I assured her there was no genetic curse. Then it happened. Twice.

My cancer reminded me of the helplessness I’d felt then, of the dismay over giving children something—even if it was just a looming doubt—that they didn’t deserve. Later, somebody asked me how I told Patty on that day my MRI was read. I couldn’t remember. Probably I was already thinking about our kids and what I’d tell them. It was early August and their college soccer pre-season—a punishing three weeks of fitness tests and two-a-day practices—was just starting.

Ultimately, we didn’t tell them until the eve of my pre-surgery radiation at Mass. General Hospital’s Proton Beam Therapy Center. It was the second week in September 2014, and Henry was a surprise starter who’d played almost every minute. Celia was healthy and holding onto her center back starting role. I’d sat on my diagnosis an entire month.

We chose a favorite restaurant in Newton Center near Henry’s BC dorm. Celia’s team was in the area because of a game against Holy Cross. The kids were in their respective athletic gear and the signature popovers had just arrived. “So you’re saying it’s not the bad kind of cancer?” Henry asked. “Right,” I replied, “it’s very slow-growing.”

I was relentlessly positive, telling them I’d be good as new with the precision proton radiation I was about to receive and a now-scheduled December surgery. It wasn’t anywhere else. They’d get the tumor and I’d be fine. It wasn’t a big deal. Onward. By the time dinner arrived, we’d long since moved onto soccer, upcoming opponents, and in both of their teams’ cases, the dying dream of playoffs that season.

—

When I collapsed by the side of my Mass. General hospital bed, it was a surprise to everyone. Surgeons had warned there would be peripheral nerve damage, an unavoidable result of excising the cancer en bloc from in and around the spinal cord. With time and determined rehabilitation, it was expected I’d walk and be reasonably active again. But as the days and then weeks went by, it became apparent that I wasn’t getting better. Instead of being in a post-surgery rehabilitation hospital for a few days, I was there almost five weeks.

My left leg, which shouldn’t have been impacted at all, was largely paralyzed. I couldn’t feel touch on most of my leg and couldn’t raise it off the bed or wiggle my toes. My left foot—the naturally strong one that earned me a varsity letter as a freshman soccer player in high school—hung limply off the end of my leg, unable to push down or pull up. I was assessed as a T10 Class C paraplegic.

When I finally returned home, I was in a wheelchair with a rotation of friends and in-home care professionals to look after me. I was so bewildered by my predicament and new body, I left a heating pad on my abdomen for too long and badly burned myself. I’d forgotten I couldn’t feel anything.

Through one of New England’s biggest snowfall winters, I was largely housebound. I walked with a walker in endless circles around our small house and slept downstairs in a dining room our friends had refashioned into an in-law apartment. My doctors put off my post-surgery radiation treatments to give my nerves every possible chance at recovery, but the grace period produced no change.

In March, I concluded most of my radiation requirement—accepting the unusual option of subtracting a couple of treatments to improve my odds of nerve growth. My doctor understood what I was looking for. He often introduced me to colleagues as “the guy who I told you about who rode his bike to radiation appointments.” Some of his data suggested the additional treatments might not be necessary to prevent cancer recurrence. I tried to be thoughtfully reserved in considering the options—a proven protocol vs. a less-proven one—but in reality I was just pretending. I’d been told multiple times that nerve regeneration usually happens within the first year. The clock was ticking and I wanted a better ending. “I’ll do it,” I said.

—

In spite of my hope, there was no pretending anymore that cancer—and now an indeterminate spinal cord injury—was a topic of no special or lasting consequence. I struggled for an explanation.

Only a year earlier, on the eve of his first college season, I’d been at a soccer field with Henry, flipping balls at him rapid fire to settle with his foot or chest and kick back. I’d done the same drill with Celia a few years earlier, back when she was worried and coming back from her knee injury.

“My dad and I like to ride whoop-de-doos,” my son once told his pre-school teacher. The caption and the accompanying scribble sketch hung in my office. I was that dad, the drop-everything, ball-tossing, whoop-de-doo dad.

On the eve of my surgery, Celia had sent me a poem. She wanted me to know it was all going to be OK, to remind me I had the special stuff. “A road awaits you,” she’d written in part. “Just another road to take your bike out on. Probably bumpy, but you love mountain biking. Probably cold, you’ve sat through soccer games. Probably unpredictable, you’ve been in love …”

Whoever I now was, it wasn’t the protagonist in her poem. When she and Henry returned home for their respective spring and summer breaks, I felt uncomfortable in their athletic, energetic presences. It wasn’t that I needed to be at the playing field with them like I used to—I’d aged out of that—but whether I was in a wheelchair as I was in the beginning, or transporting myself around the room with steadying holds on furniture and countertops, I represented the exact opposite of what I’d promised. Different. Changed. Disabled. In the downstairs bathroom, they needed to move aside an adaptive toilet seat. My long crutches, leaned against a table or a living room couch, never failed to trip somebody up.

My progress, when it came, wasn’t sweeping but drip-like. I slept a little less, walked a little farther. After a time, I could tie a shoe, stretch enough to close a car door. When Henry came home from his summer job at BC and asked about my new outpatient physical therapy, I painted a picture of good exhaustion from supported squats and an infernal exercise machine called the “Reformer.” He encouraged me the way I had him: “Good,” he said, “it must mean you’re working hard.” Hard always promised progress. I didn’t have the heart to tell him I was losing faith: hard was just hard.

Celia was in California, having cut off her break for a journalism internship. If there was brightness, it was in the middle of the night when she’d text me, forgetting about the time difference. “I’m interviewing Kobe Bryant,” she wrote in one of them. “What do I ask him??!!!”

When I went to Boston for my first major follow-up, the good news was that I was cancer-free. The bad news was that the neurological testing revealed that I was not likely to recover from my injury. My doctors were puzzled. Their best guess was that a loss of blood during surgery had resulted in damage on the spinal cord, not outside of it. When I asked for my prognosis, the doctor called me an “N of 1.” They’d never had a surgical outcome like mine; they couldn’t say.

A few days later, I met a new primary care physician. It was a disaster. She hadn’t read my case history and greeted me, “So what brings you here today?” When I told her I couldn’t believe she didn’t know why I was there, she said she didn’t like the tone in my voice and was concerned about my emotional stability. “Do you ever want to hurt yourself?” she asked a few minutes later. “Someone else?”

I felt like I was falling. Then I fell. This time there was no one around to catch me. I’d been distracted and trying to carry something in my left hand when I stumbled in that direction. With no crutch to brace against, I simply slammed to the blacktop. I screamed, more out of shock and exasperation and horror at what I’d become, than from the pain of impact. Nothing was broken.

“What, what, what?!” Patty hollered, running out of the house toward the backyard. She helped me roll up onto my side and held onto a patio chair as I slowly inched up it from the ground. We were alone, mercifully.

For a long time, I sat silently in the chair, at the edge of our catalpa’s broad-leafed canopy. Since I’d checked into the hospital last December, I’d gone from young to old, from husband to dependent, from my kids’ most dependable companion to their least. People with my lumbosacral spinal cord injury often could expect serious secondary issues like spasms and loss of bladder and bowel control.

Friends and family had come through. Everyone had been trying so hard. Neither Patty nor Celia and Henry had wavered in their support. I feared less for their ability to handle what might be next than for my own.

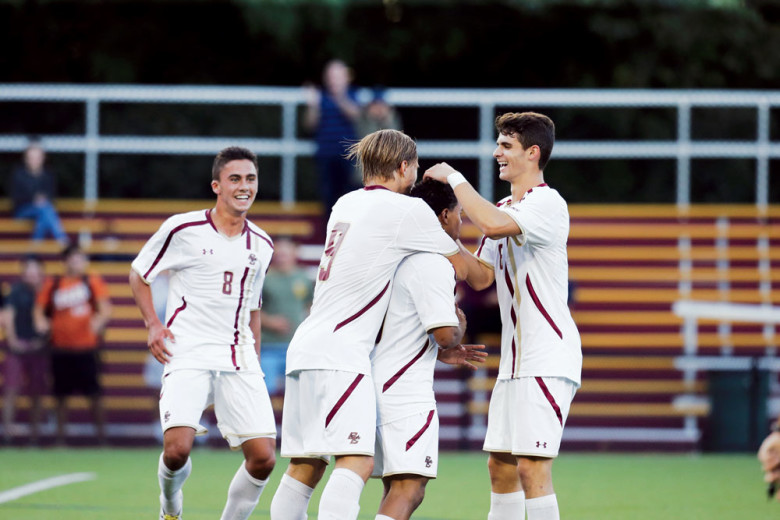

Photo Credit : courtesy of Boston College Athletics

—

Throughout my recovery, I’d approached it as an athlete and focused on what my body was telling me. But the language of the injury was different. It wasn’t just the extreme weakness in my legs, but a type of chronic pain I’d never experienced and had trouble describing. One day I felt my leg engulfed in a tightness like a spasm; on another my abdomen ached with hernia-like symptoms. The symptoms might disappear in minutes or stay for days. Sometimes I felt a little dripping of water inside me, so real-feeling I’d put my hand to my waist expecting the skin to be damp. But it never was. My world was narrow but unknowable.

When the 2015 college soccer season started, I reflexively did what I always did: pull down the kitchen wall calendar and scribble in game dates and locations. It was Celia’s senior season; BC was close by. My plan was complicated by one fact above all others in late August: I didn’t have a license.

I hadn’t much missed my “surrendered” license in the late spring and early summer, with friends and family delivering me to physical therapy and medical follow-ups. But with upcoming games in mind, I needed it back.

I expected a delay in getting the paperwork approved. In the interim, the idea of an illicit test drive grew on me. I simulated everything in the driveway: raising my foot to gas pedal and brake, twisting my reconstructed back to glance over each shoulder. When I accelerated away from my driveway in Beverly for the first time, a jolt went through me like I was dropping down a steep New England mountain bike trail. It was my first recovery adventure. I went to Stop & Shop.

A week later, with my license actually in hand, I drove to see Celia play. UAlbany’s thumping 4-1 victory over Quinnipiac was fine reward. Afterward, Celia would ask a teammate to snap a father-daughter pic, our first since my surgery. I’d find it “liked” like crazy on her Facebook feed later that night: “Look who made his first road trip to see the Lady Danes victory!” Celia wrote.

The “trip” was a solo, 300-mile round-trip to New Haven, Connecticut, in a borrowed 2001 Volvo.It might not have been the smartest idea. But when word of the journey spread to friends and family there was a consensus response: knowing smirks. The old Todd—the goal-or-bust nut who once played in a middle school basketball game with what turned out to be scarlet fever—had unexpectedly surfaced.

The next day, I dragged down the wall calendar again and added road trips to Albany, Stony Brook, and Burlington, Vermont —meaning I’d see every one of Celia’s games in October, her final month of the final season. Unfortunately, my presence didn’t spark a storybook run. The team’s early-season promise vanished with a string of tough conference losses, including a crushing late defeat to rival Hartford.

Henry’s team followed the same trajectory—some solid early-season victories (including a rousing 3-2 win against rival BU in front of 8,000-plus fans) followed by dispiriting conference losses. If anything special was going to happen for either team, each would have to pull off late-season upsets—Celia’s team at Burlington and Henry’s against nationally ranked Syracuse.

My progress wasn’t dramatic in the same time period, but I did notice behavior shifts. Before a game at UNH —where a sizeable friends-and-family contingent came out for Celia—I swapped out two forearm crutches for a single StrongArm cane for the first time. I baked the coconut oatmeal cookies everybody liked for the tailgate.

When I’d thought about recovery prior to surgery—and it wasn’t much —I’d imagined an exceptional one. Of course I knew there would be a few slow months, but I’d taken care of that with a file I called “What Will Todd Do When He Can’t Do Anything?” The file was filled with quirky, long-set-aside pursuits —learning an instrument, adding a language. And then I’d done none of it. In showing up to games in September and early October, I wasn’t setting the world on fire, but I wasn’t hiding either.

The spate of doctors I’d seen in recent weeks—a neurologist, a physical medicine specialist, a nerve surgeon—all agreed that I was making strides. Even the disappointing doctor who’d operated on me made an impression, wondering if I realized that 15 percent of the patients with my severity of chordoma died on the operating room table. Maybe Patty was right, that the hallmark of my experience wasn’t a “complication” that paralyzed me, but survival.

Our marriage was nearing 30 years. We’d once differed over soccer and how I’d allowed it to take over our family lives; holidays like Easter and Thanksgiving were travel tournament times. Club soccer cost time and more money than we had. I worried too intensely about their rise in a sport that was often cutthroat and all-consuming.

Now, though, Patty sensed an opening and made sure we prioritized the games. She brought extra pillows, soft blankets, and enough snacks for an overnight. In the beginning, we sometimes arrived a few minutes late to slip into the crowd more anonymously. At the UMass game, she parked practically on the sideline when I wasn’t walking well. “We don’t have to stay for the whole game,” she’d sweetly lie.

Photo Credit : Bill Ziskin Photography/University at Albany

—

The Vermont game featured biting gales and intermittent snow flurries, but Celia’s Albany team summoned their best performance of the season in a 2-0 victory. It was the start of a five-game win streak, includingtwo games in the playoffs. Against Hartford, they scored two goals in the final minutes to win the first conference championship in school history.

Henry’s team defeated Syracuse 2-1 at BC’s home field, a victory that would earn them an invitation to play in the NCAA tournament. Of the nearly 400 Division I schools to start the year, BC would be one of only 64 invited to play for a national championship. He was happier than I’d ever seen after the game. They’d go on to win their first three games in the tournament including an upset of Georgetown, the top-ranked team in the nation.

Watching that game and Celia hoisting overhead the championship trophy within a few weeks of each other gave me chills. I reminded myself that my children’s exploits had nothing to do with me, that a season is just a season, sports just sports. I wasn’t the benefactor of some compassionate cosmic nod, one that had assessed my tough run of late and my vast dad dreams, took it upon review, and said, in effect, “Let’s throw this poor guy a bone.”But then, I looked at the calendar and realized the soccer Final Four coincided with the anniversary of my surgery. I did wonder. BC was a win away.

Alas, the team’s journey ended the following weekend in the “Elite 8” round, to ACC champion Syracuse. Maybe it was for the best. We were exhausted. Both Celia and Henry had made long trips to see the other play in the middle of their semesters. We’d driven to Penn State, Washington D.C., and Syracuse —twice. I’d gone to nine games in September, another 18 in October and November.

In taking stock of the journey we’d been on, I realized the games, intentionally or not, had become rallying points for my recovery. Each one was an opportunity for a touch, hug, or laugh. The night before Henry’s Syracuse game, I’d joked with an old friend living in Cleveland that the game was right around the corner. Minutes later he texted, “I think I’m in.” Dan was in the parking lot waiting for us when we arrived.

The kids’ gift to me wasn’t a conference championship or an Elite 8 “run,” but a providential, long-running show where others could readily find me. When you feel diminished, it’s easier to feel so alone. As the season unexpectedly lengthened and gained steam, I was inexorably drawn back into my life.

—

On New Year’s Day, a few weeks after the greatest season we’d all ever been a part of, I had what in the old days they might have called a breakdown. Both kids were home from break, the same tensions were building, me and them and the dad I’d become. For sure, it wasn’t a big deal, the trigger that is. In another household, it could have been a towel forgetfully left in the hallway, dishes in the sink. This time it was my adaptive toilet platform. Celia left it in the middle of the bathroom, roughly set aside. And it set me off. The gesture suggested what I feared most: that in their eyes, I wasn’t measuring up. I’d gotten comfortable with my disability and they’d noticed.

All of it would be a surprise when I later shared my reaction. All anyone knew was that I buried myself in our bedroom and they left for a crazy midwinter ice cream fix without me. What they also didn’t know until many hours later was what I did in the half-hour they were gone: I threw it all out. All the adaptive gear. Down the side entrance stairs. Out the first floor bathroom window. For a few minutes it was all out in the yard or driveway—the shower seat, the walker, the toilet seat and its platform, the boots that were supposed to do something they never did. I dragged the gear into our barn, shut the door, and returned to my bedroom, my heart pounding.

That night, for the first time, I tried to explain myself, my feelings, the frustrations and grief over the person I no longer was. I went from Celia’s room to Henry’s and back again. “Why didn’t you tell us?” Celia asked—like everyone I’ve loved has asked at one time or another.

I’ve always had a fear about the dad I might be. About making a mistake I couldn’t take back. Our lives aren’t supposed to intrude into theirs. Maybe I didn’t have the proper faith in their resilience, forgetting they weren’t the fragile ones. What was less wrongheaded, and maybe helpful, was that their place in our lives made me dig deep for my better self. I’ve always been able to dig deep.

After New Year’s Day, we moved forward. I had them dismantle my day bed and I moved upstairs again. In its stead they brought down a large oak desk, so I could write. At the next school break a few months later, the two of them put me on an upright bike and ran alongside until I said it was OK to let go. In the video Patty filmed, Henry is beaming, I’m laughing, and Celia is looking into the camera, both thumbs up.

It’s impossible to know what will come. There are ups and downs in every season, every recovery. I probably won’t ever regain full use of my legs, but I’m active and pushing. In my best moments, I think being an “N of 1” is my biggest adventure. Some 80 percent of my leg strength may be gone, but I look forward to getting the most of what’s left. I like what one paralyzed cyclist said about his success in carving out a place back in the sport he loves: “I haven’t actually changed much;I’ve just learned a lot.”

I aspire to something similar. I think I’m on my way. I know I have the team for it. I love my team.