Sawdust In His Veins | Sawmill Traditionalist

For more than two centuries, lumber from the Wilkins sawmill has built barns and homes, redone kitchens, and framed additions. Tom Wilkins keeps the legacy alive.

Like the seven generations of Wilkins men before him, Tom Wilkins has found his calling in working hard and close to the land. “I met him when he was 15,” says his wife, Sally, “and he knew then that he was going to work at the mill.”

Photo Credit : Jarrod McCabeFor more than two centuries, lumber from the Wilkins sawmill has built barns and homes, redone kitchens, and framed additions. Tom Wilkins keeps the legacy alive.

The frigid early-February morning isn’t doing Tom Wilkins any favors. “Nothin’ wants to start,” he grumbles as he stares at his front loader, a yellow Volvo tractor that’s parked in front of a stack of recently planed 10-foot boards at his sawmill in Milford, New Hampshire. The air packs a hard, stinging bite, and across the yard towering piles of logs, long rows of boards, and pyramids of bark mulch are locked down with a thick crust of a winter that on this —10° day shows no signs of relinquishing its grip.

Photo Credit : Jarrod McCabe

“It’s gotta be the coldest day so far,” Wilkins says in a low, gravelly voice that resembles the rumble of the diesel engine he’s trying to fire up. Dressed in black Sorels, long underwear, a thick flannel shirt, overalls, and a brown knit cap under which he tucks his graying ponytail, Wilkins has already developed a pretty good frost on his beard. His eyes stay fixed on the loader for a few more long seconds, as though he’s trying to will it to life.

“All right,” he says, then folds his 6-foot-4-inch frame into the cab to crank the engine one more time. He presses his body against the steering wheel and turns the key. It spins hard and then belches several coughs before finally, reluctantly, sputtering to life. Wilkins lets the loader idle for several minutes, then drives it 50 yards and parks it next to a blue Chevy pickup with 130,000 miles on the motor and a scattering of bumper stickers with messages like “No Farms No Food” and “Proud Parent of a U.S. Marine.” He links the two vehicles with a set of jumper cables and begins the ritual all over again.

On it goes like this for the next half-hour. The planer mill. The office. Another loader. A slow slumber and then life. As he works, Wilkins moves with the kind of purpose and efficiency of a man who’s done this sort of thing thousands of times.

Which, of course, he has.

—

Every so often the question comes up: You think you’d like to do anything else with your life? Tom Wilkins might pause, as though he’s truly contemplating the question, before shaking his head and smiling. “Nah,” he’ll say. “I’ve got sawdust in my veins.”

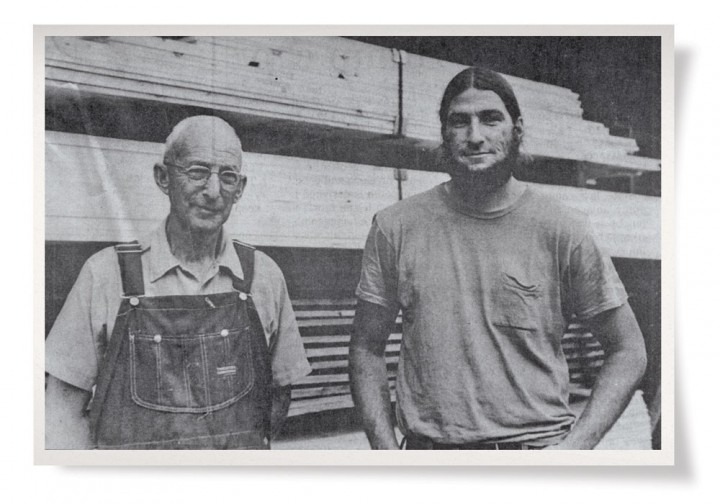

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Tom Wilkins

Wilkins packs a reverence for his work and for the sawmill like that of an artist speaking about his craft. His small family sawmill still uses the same kind of machinery it did half a century ago, and he speaks in passionate tones about the satisfaction that comes from maximizing the board feet out of a single log, or producing a stack of finished lumber. Get him going and he might tell you about the best band saw he ever encountered. (“Dick Marble’s in Hollis—he knew how to saw real lumber.”) Or the peace he’s found being at the mill on his own, working the planer deep into a muggy, star-filled August night to churn out finished floorboards and trim.

For more than two centuries, Wilkins lumber has built barns and homes, redone kitchens, and framed additions. Drive down nearly any residential road in southeastern New Hampshire and you’d be hard-pressed to find one without at least one property that was built using Wilkins boards. In some areas, whole neighborhoods bear the stuff.

Lumber has sustained eight generations of Wilkins’ family:men who found their calling in working hard and close to the land. When Wilkins was born in 1959, the family business was part of a thriving group of southern New Hampshire lumberyards that were turning out local boards for local builders. By then, Tom’s grand-father, Harold Wilkins, a kind man with a penchant for story-telling, was overseeing the operation.

Wilkins started working for his granddad when he was 12. He sorted boards, delivered stock to the lumberyard, did cleanup, whatever low-level tasks Harold needed. He worked full-time in the summer and on Saturdays during the school year. On those weekend days, after the mill closed, grandson and grandfather continued their work by walking the family land, double-checking property markers and pruning hemlock. The woods packed stories, and Harold knew many of them. He pointed out the old cellar holes and reminisced about the big spruce that had once prevailed. The work, the way of life, the chance to be outside, catered perfectly to Tom Wilkins, who later built much of his vacation time around hiking 14,000-foot mountains out West. At the insistence of his grandfather, Wilkins went to college and earned a business degree from Bentley University in Waltham, Massachusetts. But as soon as he could, he returned to New Hampshire and began working at the mill for $160 a week.

“I met him when he was 15,” Wilkins’ wife, Sally, said, “and he knew then that he was going to come back home and go to work at the mill.”

The couple married in 1981 and settled on a remote piece of family property in Amherst that Harold had given them as a wedding present. They built a house, raised five kids, and started a small farm. After Harold slowed, Wilkins took over running the mill. When his kids needed to see him, they cut along the short forest path that runs between their home and the sawmill. Everything the Wilkinses did, how they lived, how they worked, emanated from the land they owned. And in increasingly upscale Amherst, home to a booming community of Boston commuters with big new houses, they stood apart.

“I had friends who lived in Bedford on a hill in mansions with giant swimming pools,” says Tom and Sally’s daughter Rachel. “It was a little embarrassing, because in school we’d actually go on field trips to our house to see our farm animals.” She laughs. “I think in winter we were the only kids in school who didn’t want snow days, because that meant we’d have to stay home and work.”

—

Wilkins knows he’s an anomaly. Gone are the sawmills and so many of the farms that once dotted Amherst’s landscape. Fields and meadows have given way to house lots and commercial development. Around the mill is a community more accustomed to commuting and the quiet hum of computers and air conditioners than to the whirling buzz of big planers and giant saws.

It’s one of the reasons why two years ago Wilkins and his wife put much of the family land, more than 500 acres, into conservation. Selling it to a developer would have given them a couple million dollars and eased the financial burdens they’ve had to stare down over these past few years. But in doing so, the Wilkinses knew that the area would lose something it would never get back.

“There just aren’t that many places around here where you can get out and not see a house,” Sally says. “Where you can just look up at a dark sky.”

Photo Credit : Jarrod McCabe

It was a stark reminder that not all property is valued by how many house lots can be squeezed into it. For Tom Wilkins, that outweighed the stress of wondering whether he could retire or how he could keep the family sawmill going when so many others have closed.

“People think we live in the country,” Wilkins says. “This isn’t the country. This is suburbia. We’re just bedroom communities, and the problem is, this is physical labor. These days, you can go to Walmart and get a job for not a whole lot less money than what you can make here. Plus, you’re inside—you don’t have to worry about freezing on a cold day.”

Wilkins feels that. At 55, with one knee replacement on the books and another one needed, he’s weathering the effects of four decades of hard labor. He still puts in regular 14-hour days, but his body has lost a step; ailments crop up more often. Last summer he gutted out three hernias, waiting until Christmas, when he could shut the mill down, to have the surgery. “I just don’t get as much done during the day as I used to,” he says.

It’s made him wonder about his future and the mill’s. None of his kids wants to take it over. He wishes it weren’t so, but he also hasn’t pressed the issue. It’s a way of life that can’t be pushed. If you don’t love it, he says, there’s no way you’ll survive it. And that passion becomes an emergency resource to draw on when the temperature dips below zero and you’re working outside all day.

—

At a little before 7:00 a.m., most of Wilkins’ five-man crew have filed into the mill’s small office, where a big framed picture of Harold Wilkins hangs on the wall and a dusty, 10-year-old computer is shoved in the corner. Nearby, a small notebook and pen, the preferred tools for recording orders, sit by the phone.

In this room, at this hour, the men talk like old friends. Many of them have worked here for decades. The mill’s sawyer, Dennis Cluche, a soft-spoken man with a thick white goatee, started in 1969. His brother, Chris, came on a few years after that. For Tom Wilkins, any talk about the mill’s future invariably includes these guys. He’s loyal to them, to the life they’ve carved out for themselves by working for his family’s business. He knows that the legacy of the mill includes more than just his bloodline.

While John Pasquariello, who handles deliveries, talks about the winter triathlon he recently completed, Wilkins receives a text from his debarker, Bill Jones. He’s running late. “Looks like his dogs crapped all over the place and he had to clean up,” Wilkins says, smiling, as the room erupts in laughter.

Ten minutes later, Jones sheepishly comes through the door and absorbs a few jabs, before talk turns to the weather and the day at hand. The inventory is low on 10-footers, and there’s also the matter of the 4,000 hemlock posts the sawmill has been hired to make for a dredging project in Massachusetts. “I’ll make sure I chip snow off the stack of 12-footers,” Wilkins says. “I keep meaning to do that, but every time I try, something else comes up.”

When the workloads have been sorted out, the guys trickle out of the warm office, toward the lumber and the machinery. “Back to the planer mill,” Wilkins says, pushing the door open. He steps out, where Pasquariello is looking around the yard. A blue sky is emerging. “It’s starting to warm up,” he says. Wilkins arches his eyebrows as if to say, Maybe. Then he heads to the planer. The mill is now open. A day’s work lies ahead.

Ian Aldrich

Ian Aldrich is the Senior Features Editor at Yankee magazine, where he has worked for more for nearly two decades. As the magazine’s staff feature writer, he writes stories that delve deep into issues facing communities throughout New England. In 2019 he received gold in the reporting category at the annual City-Regional Magazine conference for his story on New England’s opioid crisis. Ian’s work has been recognized by both the Best American Sports and Best American Travel Writing anthologies. He lives with his family in Dublin, New Hampshire.

More by Ian Aldrich