New England Energy | Power Struggles

Here’s the dilemma: New England needs energy, but every proposed solution comes with risk, potential environmental damage, and public anger. First in a two-part series about New England energy.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanHere’s the dilemma: New England needs energy, but every proposed solution comes with risk, potential environmental damage, and public anger. First in a two-part series about New England energy.

Photo Credit : Carl Wiens

New Englanders, you stand accused: You’re not easy. You have a lot of ideas about how your countryside and your towns should look. You don’t want pipelines, windmills, or big power plants. “It’s virtually impossible to build anything in New England,” one energy analyst says, “because transmission lines are hard to site, gas pipelines are hard to site, and wind farms—God forbid.”

And, Big Utilities, you also stand accused. You don’t reveal your plans until they’re already well developed. “We know we need energy if we want to keep the lights on,” says the head of one conservation land trust. “What we’re saying is: Don’t impose a solution on us that doesn’t allow us to be a part of the process.”

Take these two comments as shorthand for the battles being fought all over New England: in New Hampshire’s North Country about Hydro-Québec |and Northeast Utilities’ proposed Northern Pass, a 192-mile-long high-voltage transmission line; on ridgelines in Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine over windmills; and in Connecticut, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Maine about building new natural-gas lines or expanding old pipelines.

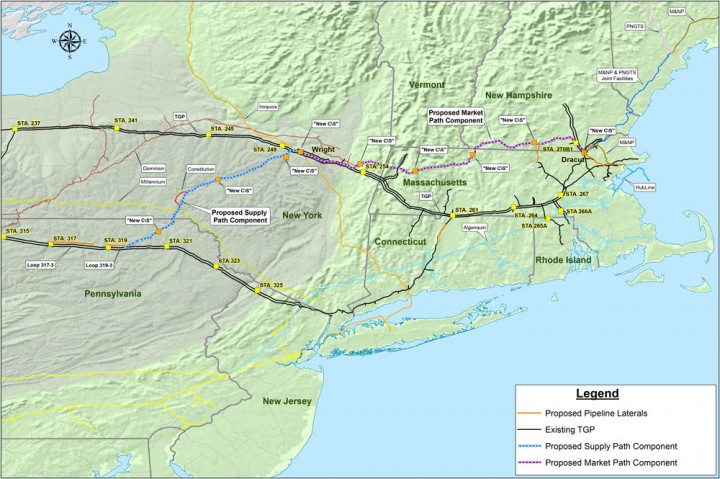

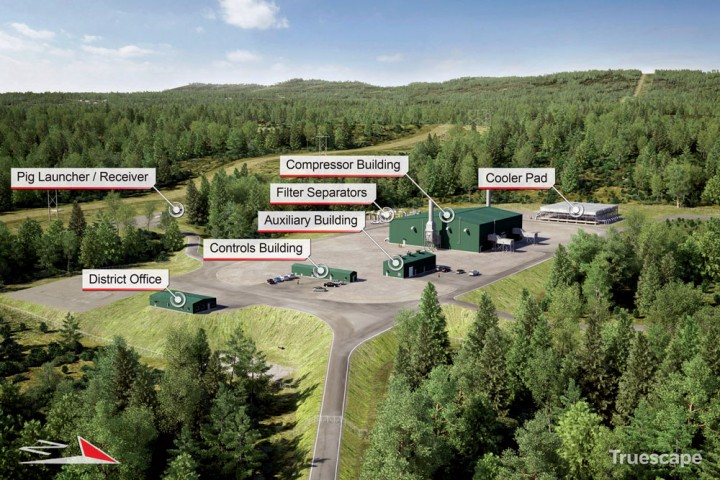

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Tennessee Gas Pipeline/Kinder Morgan

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Tennessee Gas Pipeline/Kinder Morgan

For the last year and a half I’ve been following one of these energy battles, a natural-gas pipeline that at first was routed through Massachusetts, and then leapt the state line, for part of its journey, into New Hampshire. The proposed pipeline’s arrival in town was met by a civic version of the stages of grieving: disbelief, anger, organizing. I’ve sat at kitchen tables with anguished families as they talked one minute of a beloved old tree and the next of the Constitution. I’ve sat late into the night at formal federal meetings, as speaker after speaker tried everything to drive off what they perceived to be the monster at the city gates: reasoned, factual testimony; fiery Patrick Henry oration; and the sending forth of eloquent children to speak for the earth.

At one meeting, a woman, her voice quavering, got down on her knees and begged for her home, her deck where her family loved to play cribbage, and her 22 acres with its woodlands, fish pond, stream, and a night sky “so dark you can see the Milky Way in all its brilliant clarity.”

“Our home life is simple, but it is awesome, and it is our American Dream come true,” she said. But a letter with a map had arrived in the mail; their home would be just 1,500 feet from a compressor station. “Our home has been effectively condemned … I’m begging you,” she said, falling to her knees. “I’m begging you.”

This isn’t just her problem, or that of all the towns along the route. We’re all facing serious choices that will determine how we produce electricity for years to come. The debates are accompanied by a blizzard of statistics, a complex path through the government’s regulatory agencies, and a mismatch between big corporations, with their legion of experts, and the hastily formed battalions of citizen-activists, who are rapidly educating themselves. These fights with their contending forecasts and solutions are hard to judge and harder than ever to present in an era of twitchy attention.

The utilities have the advantage. They set these projects in motion; these things are years in the planning. They can easily afford the studies and lawyers. They’re poised to answer the technical questions. The process relies heavily on their information. Activists fight to confront the planners’ assumptions: If the overall demand for electricity is stagnant, why build this project? What about alternatives that reduce demand during peak hours?

Beyond the technical debate is a question that cuts to the most essential issue. The project proponents ask: How are we going to get anything built? If not here, where? If not now, when? But that question ignores one of the bedrock questions of the republic’s founding: What’s the greatest good for the greatest number of people? And who gets a say in that decision? In short: Who sacrifices? Who benefits? Who decides? That’s what the first of this two-part series on New England’s energy landscape will explore.

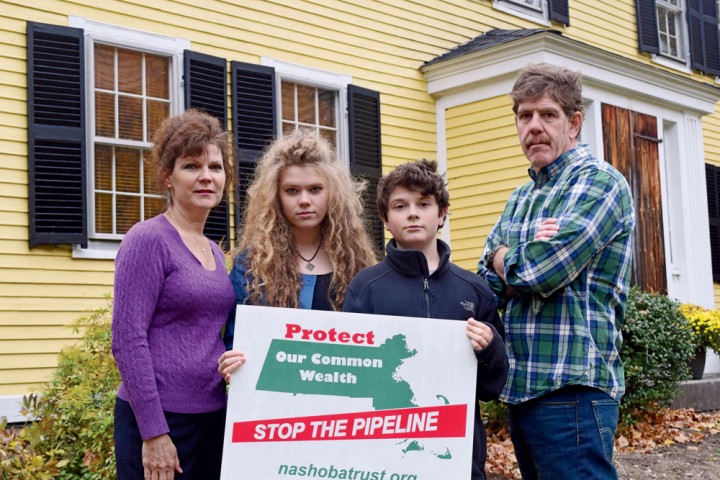

Most people don’t go seeking these problems; most people are recruited. Being thrust suddenly into the heart of the debate usually starts with a stranger at the door. That’s how it began for Vince and Denene Premus, back in the winter of 2014, much as it continues to happen in towns small and big across the region.

The Stranger on Your Doorstep

One morning in January, two years ago, Vince Premus was leaving for work when he met a man in the driveway of his home in Pepperell, Massachusetts. Did Vince have a minute? There was something he wanted to discuss.

He laid out a map on the hood of his car and made it seem like a routine matter: A 36-inch-diameter, high-pressure, natural-gas pipeline would be going right here, crossing the Premuses’ small field, right where Vince, his wife Denene, and their two children play soccer and lacrosse and fly kites. It’s where they’ve held Halloween-party sack races for 50 children. “It’s a wonderful place to be outside,” Vince told me. “In the fall it’s incredible how beautiful it is.” The pipeline would flow 200 feet from their house.

The company representative wanted Vince to sign permission to survey his land or, failing that, to sign a form saying that he didn’t give permission. Vince refused. He was late for work (he’s an engineer studying ocean acoustics), but he detoured to the Pepperell town hall to find out what was going on.

Photo Credit : McKenna Premus

Town officials didn’t know much more than he did: just that Kinder Morgan, North America’s largest energy infrastructure company, based in Houston, Texas, wanted to build a natural-gas pipeline called Northeast Energy Direct across New York State and then 180 miles across northern Massachusetts. This scene was playing out in town after town: a stranger knocking, saying something about a pipeline, rumors and questions all over town.

It seemed unreal to Vince and Denene. How could some Texas company lay claim to their land and, as they saw it, threaten their safety? Since 2003 there have been more than 20 serious accidents, including fires and explosions, on Kinder Morgan’s pipelines. Kinder Morgan counters, saying that it “consistently outperforms the industry averages in virtually all environmental, health and safety measures.” But “industry averages” can be discomfiting. On other companies’ pipelines, three major accidents in the last five years have killed eight people, injured more than 50, destroyed 41 houses, and damaged many others.

In April the Premuses received a letter with a brace of legal citations stating that they couldn’t refuse, that Kinder Morgan could survey their land anyway. “It was pretty aggressive,” Vince said. “It’s when we knew we were really into something.”

And that was for openers: If the pipeline won federal approval, Kinder Morgan could take the Premuses’ land by eminent domain. Almost all pipelines are approved by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), according to one independent nonprofit that monitors pipeline safety. And further, the Premuses and everyone else plugged into a utility in New England would pay for the pipeline’s construction with a “tariff” added to the utility bills of everyone in New England.

After that January morning, the pipeline wedged itself into the Premuses’ life. They studied energy policy, organized their neighbors, picketed in front of the State House. The pipeline became their unpaid job. They attended countless meetings. Denene addressed so many letters to legislators that her son memorized their names—he helped her address the envelopes. She wanted her children to see that “you have a voice as well as a vote.”

When I visited, Denene and Vince brought out papers and files, which Vince had stacked as neatly as a deck of cards. The pipeline had put part of their life on hold. Their home is a big, welcoming farmhouse built in 1730, decorated with Denene’s quilts, appliqué, stenciling, and a few Shaker reproductions. It’s an airy, cheery household. When they first saw the house, it reminded them of their country roots in New Hampshire. When I met them 15 years later, Denene said that the way she felt about their home was like grieving: “It’s amazing how life was going along until we got this knock at the door.”

At pipeline meetings, I met many people who are united by the same story. The pipeline has become the immovable object against which they throw letter after letter, emails, phone calls, meetings, rallies. It upends normal life. They stay up late at their computers taking a crash course on energy policy. The rest of us, obliviously turning on our lights, knowing little of how electricity gets to us, are in the dark.

One day you’re taking your son to Cub Scouts, commuting to work, thinking of redoing your kitchen, and the next day your house is full of boxes of papers and your dinner talk is all about gas pipelines, the electric grid, and a dizzying array of governing agencies and regulations: FERC, ISO-NE, NESCOE, NEPOOL. From the moment someone draws a line across your land, you’re already living with the pipeline. Once it’s proposed, your life has changed—maybe forever.

—

If Kinder Morgan’s pipeline has been sketched across the map of your town, sooner or later you’ll meet Allen Fore, the company’s vice president for public affairs and its public face for the pipeline in New England.

Fore is a skilled spokesman, delivering a sound bite for the TV news or giving a detailed answer at a public meeting that tends to hold off follow-up questions. One on one, he seems to enjoy challenging questions the way others enjoy returning a serve in tennis.

The pipeline “is transportation, servicing customers” he has said at 40 town meetings in Massachusetts and many more in New Hampshire. Kinder Morgan will build it only if the company has “firm contracts” with customers; in fact, that’s required by federal regulators to approve the project. “We don’t pursue projects that we aren’t confident in securing both [customers and approval],” Fore says.

Fore wants the public to understand why the Northeast Energy Direct pipeline was proposed in the first place, and he knows his statistics: In New England, the amount of electricity generated by natural gas has increased from 15 percent in 2000 to 44 percent in 2014. In recent winters the cost of energy has spiked during the morning and evening hours on anywhere from 10 to 27 days. There’s a “pipeline bottleneck,” resulting in the nation’s highest natural-gas prices, says ISO-NE (Independent System Operator New England), the nonprofit agency responsible for operating the grid. “The region is challenged by a lack of natural gas pipelines,” it claims. The pipeline’s critics counter that this pipeline is not the solution.

To answer those who ask, Well, what would you do? pipeline opponents say: Repair and expand existing pipelines; change the way utilities buy gas so that it’s cheaper; use liquefied natural gas, which can be stored and delivered for far less than what a pipeline costs; and increase solar power and energy efficiency programs. “The incremental expansions of existing natural-gas pipelines, as well as the current supplies of liquefied natural gas that we have on the system, would be plenty to make up the shortfalls that we’ve been seeing in the winter months and reduce those price spikes,” said Shanna Cleveland, a former senior attorney with the Conservation Law Foundation.

—

At one point toward the end of my visit with the Premuses, I looked at a five- page letter that Vince had written to the assistant attorney general of Massachusetts. “You’ve written a letter with 13 footnotes,” I said. The letter takes issues point by point. It’s like something a consultant would have prepared. In fact, Vince is a consultant; he has a Ph.D. in electrical engineering. He can spot an inconsistency in numbers or practices a mile away, it seemed to me.

And although he’s as rational as you’d expect an engineer to be, he’s also impassioned. At one point while we were talking, he choked up as he was telling me about the feeling of solidarity that comes over him at the homeowner meetings as he looks at his neighbors: “We’re all in this together. Your home is just as important as my home.”

He stopped, eyes red. “If they build this thing and I didn’t fight it, I won’t be able to sleep. I won’t be able to live with myself. You have to fight this fight. You have to be true to yourself. You have to do what makes sense in your own heart. And if you don’t do that, you’ll regret it for the rest of your life.”

He sat with his head in his palm for a moment, and after finishing his thought, left the table.

Big Plans

The Premuses’ is just one household among thousands of others sitting in the way of a 180-mile-long section of one natural-gas pipeline. There are, at this moment, plans for thousands of miles of new pipelines and electrical transmission towers in the United States, as well as new windmills sketched in for almost every ridge and view. The way power has been generated for a century is changing rapidly. The map is crisscrossed with plans. Anyone may be in the way of the next big project slicing across the countryside.

Our power grid is like the “tangled maze of poorly maintained roads” that we had before the Interstates were built, President Obama said in 2009, calling for a “clean-energy superhighway.” The National Renewable Energy Laboratory is advocating 10 major powerline corridors to deliver the electricity from big solar and wind projects. The windiest areas are where the population is sparse, and the only room for big solar projects is out in the last wide-open spaces. (Renewable energy is not a Get Out of Jail Free card. It’s not that simple.)

In New England, Kinder Morgan’s Northeast Energy Direct pipeline is competing with at least four other planned natural-gas pipelines, some of them in existing rights-of-way. Nationally, 100,000 miles of natural-gas pipeline—main lines, laterals, and gathering lines—have been built in the last dozen years, and more than 300,000 miles may be built in the next 20 years. New pipelines leading to planned gas-liquefaction plants are radiating out of Pennsylvania’s shale gas fields. While the 1,179-mile Keystone XL pipeline to bring Canadian tar-sands oil to the Gulf Coast was starring in the national news, all these other projects have been making waves locally. But Americans have yet to realize the large scale of these industrial projects, often inserted into the last rural landscapes. There’s no place left beyond the reach of industrial development. With each new pipeline and transmission tower, we’re choosing winners and losers. Corporations are battling citizens, and citizens are in a dogfight with their fellow citizens. It’s a turf war.

—

Each proposed pipeline or transmission line arrives wrapped in a thicket of technological details. Battles are waged over “low-demand scenarios” and “forward-capacity auctions,” but the anguish of these confrontations is lost in the tech talk. What’s at stake can be seen by looking at another powerline war.

In the 1970s in Minnesota, some farmers were told that a high-voltage powerline was going right across their farms. If they refused to cooperate, the power company would take their land by eminent domain. They asked their county planning commission to stop the powerline. Just as the commissioners were going to agree, the power company changed the rules for reviewing the project, and it went to the state. Hearings were held, and the power companies won.

After their defeat, some farmers turned to sabotage. Men and women who set great store by their neighbors’ opinions and proper living toppled at least 14 high-transmission powerline towers. Some farmers backed a reform candidate for governor, Alice Tripp, a farm wife who had never run for any public office. As Tripp campaigned, she summarized the great challenge of these large projects, asking, “Who sacrifices, who benefits, and who decides in America today?”

“What happened to the farmers of western Minnesota is happening to all of us,” Tripp said in 1978. “Partnerships of large corporations and entrenched bureaucracies dominate the vital decisions that affect our lives and shape our future … This is not democratic.” (Tripp received 20 percent of the statewide vote.)

Who sacrifices, who benefits, who decides? That’s being asked all over the country. These three questions are a clarifying lens. Homeowners along the ever-shifting proposed pipeline route are being asked to sacrifice—but for whose benefit? And what say do they have?

None of the pipeline’s planners would call families like the Premuses “stakeholders.” That term is reserved for the pipeline company and the agencies that oversee it. “The ironic thing to me,” Vince noted, “is that the real stakeholder—the one who’s investing, against their will, by the way—but the one who’s really investing, who has skin in this game: It’s us. They’re going to take our property.

“If you measure the size of our stake as a percentage of our net worth, we have far more invested in this process than even Richard Kinder himself,” he said, naming Kinder Morgan’s CEO. “And yet we have no say—no real say. We’re not invited to the table as a stakeholder. The time has come to actually update the definition of stakeholder and give people like us a seat at that table. There should be representation.

“You should never ever come to some homeowner and say, ‘We’re going to take your land whether you like it or not, because we think that this is needed,’ unless it’s an absolute last case. When you say you have to put a pipeline 200 feet from my children’s bedrooms, you’d better have tried every other option first. There’s nothing that they can do to me that’s more serious and more threatening than what they’re proposing to build outside our doorstep.”

—

Two months after I visited the Premuses, Vince and four other landowners did get a seat at the table as stakeholders—for one meeting. For three hours they met with Gordon Van Welie, the CEO of ISO-NE, and four of his staff, in the conference room overlooking the operations floor where ISO-NE manages New England’s electric grid.

Vince’s group pressed Van Welie to look harder at using renewable energy and efficiency programs to reduce peak demand. The public is receiving a message that gas pipelines are the only option, they told him. Van Welie conceded that they could present a more balanced range of options, but he emphasized that as older power plants retire, the grid managers are “painted into a corner.” They’re “right at the edge” during winter peak-demand hours. Only an “incremental” increase in the supply of natural gas could meet the shortfall in the shortest time, Van Welie said. He doesn’t think that renewable energy or energy efficiency would be enough in the short term.

Vetoed

Townsend, Massachusetts, lies six miles west of the Premuses’ home. I toured the town with Carolyn Sellars, a busy volunteer, and Leslie Gabrilska, the town’s conservation agent, the paid staffer for Townsend’s conservation commission. Sellars is jovial. She talks fast—she kind of percolates—and she seems relentlessly happy. Gabrilska is serious, quieter, with the demeanor of a deliberating official.

Photo Credit : Michele Hirsch

They showed me the planned pipeline route. I immediately saw why Gabrilska was one of my guides. A tour of the proposed pipeline route is a tour of conservation land. It looked as though Kinder Morgan had stitched together the green spaces on the map. Each time the car paused, the two women pointed to a state forest, a brook, or land conserved in a town trust, each with its own Eagle Scout project to mark the walking trails; I might have seen a decade’s worth of Eagle Scout projects. Kinder Morgan picks bigger open spaces because it’s easier than dealing with many small landholders, Sellars said. Fore, the Kinder Morgan spokesman, denied that, explaining that the company is trying to balance environmental concerns and the interests of private landowners.

This is hard-won land, assembled with deals to build clustered and affordable houses, put together with state money and private donations. Townsend was one of the first communities to allow denser housing developments in exchange for setting aside open space. Massachusetts has designated two-thirds of Townsend as an “Area of Critical Environmental Concern.” There are a state park and forest, two state wildlife areas, and the closest cold-water fishery to Boston. The state has heavily invested to protect Townsend.

At one of our stops, Sellars and Gabrilska showed me the possible location of a huge compressor station; such facilities are required at intervals along the pipeline to keep the gas moving. Rated at 120,000 horsepower, like a continuously running gas engine, the station would be one of the largest in Massachusetts. Because of its noise, the station is required to be set off on 50 to 75 acres.

Thousands of hours of volunteer work, committee meetings, the drafting of state laws, and public investment lie behind the landscape that Townsend has curated. The pipeline and the compressor station—if Kinder Morgan sticks to this route—would threaten all this work. It would nullify the community’s and the state’s will. No to your ideas of what land should be conserved. The pipeline would be a veto delivered out of nowhere.

—

Carolyn Sellars has been here before; she has defended her family’s farm in Winchendon, Massachusetts. Her family has owned the 125-acre property since her great-grandparents, millworkers, bought it in 1901. She showed me photos of the farm first thing when we met, the way others might show off photos of grandchildren: the house, circa 1815, with the ancient maple in front. “The arborists said, ‘You really should take that tree down,’ but we said, ‘We can’t—this tree is like a member of this family,’” she told me.

The lawn by that maple is where her mother, Sellars, and her own two daughters celebrated their weddings; she spoke of the walks on trails and forgotten dirt roads to a small beaver dam and an early mill dam, and of “The Spot”—a place where Bailey Brook meanders through a hemlock grove. Everyone in the family calls it “The Spot,” as in “Let’s go for walk to The Spot.” The pipeline’s 100-foot-wide clear-cut would cross right near “The Spot.” The pipeline would bisect her family’s farm.

Twenty-five years ago Sellars helped fight off a regional garbage dump (1,200 truckloads a day) that would have been built next to her land. That was followed by a proposal to build a major Logan-size airport, and then a dragstrip with seating for 30,000 spectators. She’s been a part of the efforts that beat them all back.

“This is a marathon,” she said. “You do what you can each week, but you have to keep your life going or you’ll burn out.”

Property and Liberty

On November 7, 2014, Kinder Morgan announced that it was “seriously considering” a new “preferred” route for part of the pipeline. The pipeline now had jumped the border into New Hampshire. It would still cross into Massachusetts from New York, but now turn north near Millers Falls and then cross 17 New Hampshire border towns—plus 155 wetlands and 116 bodies of water—before turning south to meet the pipeline terminal in Dracut, Massachusetts. But this wouldn’t be its final route; Kinder Morgan was keeping its options open. It hadn’t said that it had given up on the old route through Carolyn Sellars’s farm, through Townsend, or through the Premuses’ field. It looks as though these properties been spared—or have they?

When Denene Premus heard that the route was being moved, she started to cry: “There was going to be a whole new set of people who were going to have to go through everything we had gone through, and it was going to start all over for them. There was no relief. I just felt terrible.”

Kinder Morgan gave no official reason for the move. But the project’s opponents cited the 50 percent of landowners who refused to give permission to survey, the opposition of both U.S. senators from Massachusetts, and Article 97 of the state constitution, which requires a two-thirds legislative vote to change the use of conservation land.

Photo Credit : Micky Bedell/Recorder

In New Hampshire, the pipeline became the news. Few people had ever heard about it, even though its previous route was just a dozen miles south—across the state line. Borders can camouflage things, hide all sorts of connections.

—

On a Saturday in mid-December 2014, a meeting at an elementary school in Mason, New Hampshire, was packed, maybe 175 in the room. No one had put “learn about the gas pipeline” on their Christmas to-do list, but now here they were.

The crowd was patient, almost holding its breath. It was like the first day of school—Energy School, Power Grid 101. Pipeline opponents from Massachusetts had helped organize the meeting; no one from Kinder Morgan was there. They would be soon enough.

Pipeline opponents were all over the room in their yellow T-shirts, this army’s uniform. They had sold out of lawn signs ($6); they had petitions, sign-up lists, and cards on which to mail comments to FERC. There were maps of a possible route across Mason on the walls. “The map has been changing as fast as you can print them out,” the first speaker noted.

The next speaker dove into the economics and regulation of gas pipelines and the power grid. When he said, “It’s complicated,” some laughter rippled through the room. He asked, “Aren’t you overwhelmed? Yes. And guess what? They’re not. This is their day job; it’s our night job.”

A man followed who showed a short film he was making about compressor stations. He said that they release methane and other toxins into the air to relieve pipeline pressure. Kinder Morgan disagrees, saying that “under normal operations” methane isn’t released. “When gas is vented, it is done under controlled conditions,” the company states. On other pipelines Kinder Morgan has returned to add more stations so that there’s one every 15 to 23 miles or so; the proposed pipeline plans now showed compressor stations every 39 to 50 miles. That can change, the speaker said. It can all change.

We like to think of the property we own as a sure thing. We call it real estate, after all. But just because we have a deed, that doesn’t mean it’s locked up. The community or a corporation may assert a claim on our domain. Throughout American history, the law’s attitude has been that “the quiet citizen must keep out of the way of the exuberantly active one.” Economic development—“property in motion”—has the right of way over “property at rest.” This is how many dams, mills, railroads, and highways were built: by taking someone else’s land.

This is our dual inheritance: Land is our security; it’s never secure. Property is our right; it can be taken away. To the country’s founders, says historian Gregory S. Alexander, property—land—was never just the equivalent of its market value. Land represented autonomy; it was the anchor of the social order. If “the right of property is the guardian of every other right,” as the American diplomat Arthur Lee said in 1775, then eminent domain is like an icebreaker plowing through the social order. It takes what was once perceived as solid—my land, my house—and cuts right through it, opening it to traffic and commerce. Our home place, where generations may have lived, is always “on the market,” whether we’ve put it there or not.

At the Mason meeting, I spotted Vince and Denene Premus standing on one side of the room. The gathering was like the first meetings in Townsend eight or nine months ago, Vince told me. And then I saw Carolyn Sellars. She said that the pipeline was off her farm, but that a smaller, lateral pipeline was now across the street from her home in Townsend. The pipeline has left these three people, but they’re still fighting this project. They’re marathoners. They’re here to help. They know what it’s like to show up in the crosshairs of somebody else’s plans.

Epilogue

As Yankee goes to press, there are meetings and announcements about the pipeline almost weekly. Kinder Morgan has reduced the pipeline’s capacity, going from a 36-inch-diameter pipe to 30 inches, and it has located a 41,000-horsepower compressor station in New Ipswich, New Hampshire. It has signed only one customer for the gas, Liberty Utilities, a subsidiary of a company that’s a partner in the project.

The pipeline has won support from a New Hampshire Public Utilities Commission study, which states that the pipeline will help lower winter electricity costs. Critics have countered that the PUC hasn’t adequately considered several alternatives.

Opposition has grown. At FERC’s “scoping” meetings throughout southern New Hampshire in preparation for the environmental-impact statement, local and state representatives have risen to say that at first they weren’t opposed to the pipeline, but that as they’ve studied it, they feel that they’re being asked to sacrifice so that Kinder Morgan may profit. This is an export pipeline, said one state representative. Everything else is just a fig leaf trying to hide the truth.

And in May 2015, Carolyn Sellars received a letter from Kinder Morgan telling her that the lateral pipeline is now planned for her Townsend property, not across the street.

FERC has received a record number of comments, almost all negative. In many towns along the route, fighting the proposed pipeline has become a way of life. Said one Richmond selectman, “We’ve had to become experts in a lot of things we knew nothing about until a few months ago.”

Read Part 2: New England Energy | Follow Us