New England Energy | Follow Us

While much of the world frets about what to do about energy resources and climate change, three New England communities are showing that resourcefulness and ingenuity can still make a difference. Second in a two-part series about New England energy. Read Part 1: New England Energy | Power Struggles The Milford Town Hall fills up almost an hour before the meeting. […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanWhile much of the world frets about what to do about energy resources and climate change, three New England communities are showing that resourcefulness and ingenuity can still make a difference. Second in a two-part series about New England energy.

Photo Credit : Carl Wiens

Read Part 1: New England Energy | Power Struggles

The Milford Town Hall fills up almost an hour before the meeting. It’s a small room—seating only 220—for this “scoping” session, held last July by the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission to study the environmental impact of a proposed natural-gas pipeline. It would run through Massachusetts and 17 New Hampshire towns, including Milford. As more people arrive, they’re directed to an overflow room to watch the proceedings on a video feed. Outside in the rain, pipeline opponents on the common are waving signs to get cars to honk.

It’s surprisingly festive in the hall. Many of those waiting to testify know one another and are catching up. Since the pipeline was first announced in 2014, a dedicated opposition has grown up. They populate the hall in neon-yellow “Stop the Pipeline” T-shirts, a few yellow hoodies, and some armbands. A woman gives out “Stop the Pipeline” stickers, which some people add to their armbands.

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Every now and then a young guy walks up to the front of the hall holding up two large poster boards he’s just been writing on: Clean says the first board; the second says Energy Now!!! Each time he does this, the room cheers as if we’re at a football game. Let’s go! Get in there, solar power, and fight! Fight! Fight! The mood darkens once the meeting is under way; a watchful anxiety spreads.

Clean Energy Now!!! That, in three words, is the argument of the pipeline’s opponents. Natural gas is advertised as clean, but that doesn’t account for the hundreds of chemicals used in fracking to force it out, or all the methane that’s released, say the opponents. Alternative technologies are being ignored. There’s a different future out there, they say. Inevitably they’re derided as “nimbys” (“Not in My Backyard”) but the opponents point to many communities that are saying yes to these alternative technologies—communities that are saying “Yes in My Backyard”—and yet we don’t hear very much about these “yimbys.” I set out to see for myself the future of clean energy in Maine, Connecticut, and Vermont, creating a big carbon footprint in my quest for a smaller one.

—

In the old days—let’s say 30 years ago—you had one phone company, three television networks, five or six major car brands. All of that has been “disrupted,” to use the popular word of the moment among tech entrepreneurs. All that’s really left of that old world is our power grid. That power bill you pay monthly, that’s not just your father’s bill; that’s your great-grandfather’s bill. Our grid is just an aging version of how it was in its pioneering days at the start of the last century. The joke in the industry is that if Edison came back today, he’d easily recognize the power grid. But ye olde grid is in rough shape.

The United States has more power outages than any other developed country, and it’s getting worse. Since 2000 the number of major outages has doubled every five years. In an average year a New England resident will be without power for three and a half hours; in Japan the average yearly outage is four minutes. One major engineering organization grades our power grid as a D+.

Photo Credit : Dave Cleaveland/Maine Imaging

The grid is old and it’s vulnerable. One federal study found that if terrorists shut down just nine of 55,000 transfer substations and a transformer manufacturer on a hot summer day, the country could be plunged into the black for 18 months—or more. The Pentagon is bailing out. The military knows that it can no longer rely on the usual utilities to power its bases; it’s building microgrids that can operate on their own if there’s a blackout. The Pentagon has also become the world’s largest buyer of renewable energy. (It’s concerned about our domestic oil supply. One of its studies showed that terrorists could shut down three-quarters of the oil used in the eastern U.S. without leaving Louisiana.)

A massive reinvestment is coming to improve that D+ grade, and it could revolutionize the way we get electricity. Instead of adding to big centralized power plants, new technology will be local (“distributed” is the term)— solar panels, battery backups, biomass (wood chips), windmills—and it will employ many techniques to reduce peak demand. By 2040 renewables will produce almost half of all electricity worldwide. In just the first half of last year, 70 percent of new electric-power generation in the U.S. was from renewables. “The days of monopolized power are coming to an end,” said one respondent in a survey of the utility industry. “Get smart or get out of the way.”

This is the story hiding behind the battles over building new powerlines, natural-gas pipelines, and large windmills. A revolution is underway—one that’s taking place without the protests surrounding pipelines, wind farms, and other huge projects. What does it look like?

—

The first stop on my yimby tour is Boothbay, Maine. I drive into town like a tourist, stutter-stepping down narrow streets: Is this one-way? Can I turn here? Is that a parking space? It’s this kind of three-blind-mice traffic that makes locals crazy. Desperate to live in a town where people actually know where they’re going, they put up more and more signs, which only further confuse visitors. It’s a pretty town, but this is just about the last I’ll see of postcard Boothbay. I meet Dan Blais, and we tour the backs of convenience stores, shopping centers, and an industrial park by a gravel pit—Wish you were here?—and, mercifully, the front of one inn. It’s a tour of tan Dumpster-sized boxes, white tractor-trailer-sized boxes, little tan boxes with fans, and solar panels. He talks kilowatt hours, functionality, syncing.

Blais manages GridSolar’s Boothbay Pilot Project. GridSolar is a private Portland company that, along with environmental groups, challenged Central Maine Power when it wanted to build new transmission lines across the peninsula to Boothbay to cover the peak hours of summer demand. GridSolar said it had a different solution and won the right to try it out. Eight years ago, the utility doubted it would work. GridSolar installed rooftop solar panels on hotels and municipal buildings, efficient LED lighting, backup batteries, and Ice Bears, a kind of air conditioning that makes ice at night to be used later for cooling at peak demand times. It also installed a backup diesel generator.

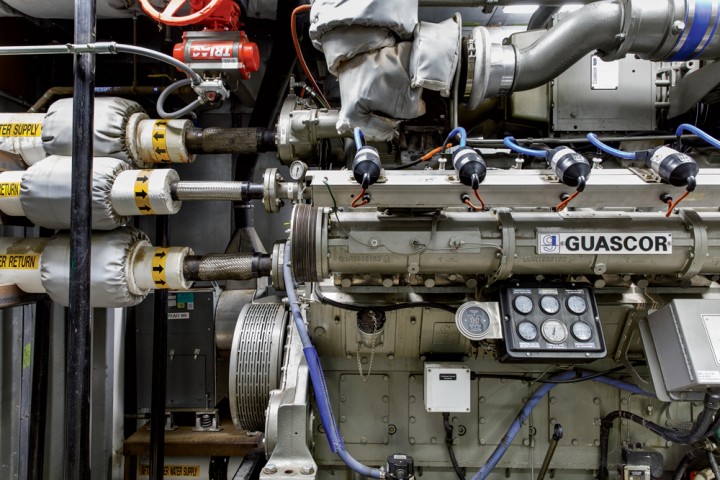

In an industrial park, Blais shows me the diesel generator, a 25-foot-long trailer known as a BUG (backup utility generator). It wasn’t anyone’s first choice; funding for a solution using renewable energy fell through. It’s not ideal, but Blais points out that if it’s called into use, the emissions would be the same as a dump truck’s. None of the backups has yet been needed; they’ve run only during tests.

Farther into the industrial park, by a gravel pit, we look at three long white shipping containers housing backup batteries. It looks like a pristine NASA installation, as though a Mars Rover could pull up alongside. Everything else nearby is weathered and worn, looking as though Maine has had its day—old, leaning tractor trailers, a left-behind boat (of course), and a big barn of a garage. But these batteries look as though they’re still an artist’s rendering, a fresh idea.

The other gadgets are unexceptional, like the Ice Bears, light-brown Dumpster-sized boxes that look like the usual stuff behind buildings. It’s undramatic, but it’s the face of the revolution going on right now. This is what the future may look like. The future was supposed to be flying cars and the Pan Am Clipper to the moon, but this might be it: incremental technological improvements going on all around us—and that’s why we’re missing it. The future wasn’t supposed to arrive wrapped in dull boxes.

But these dull boxes have produced big results. GridSolar has provided enough backup and reduced the peak demand such that the transmission line won’t have to be built, saving ratepayers $12 million. The company is looking to bring this approach next to Midcoast Maine and Portland in larger projects that could save $50 million or more.

The Acadia Center, a nonprofit that advocates for a clean-energy economy, was one of the environmental groups that fought for the Boothbay Pilot Project. “We’re very excited by this pilot. It shows that the model can work,” says Daniel Sosland, the center’s president. “The energy future isn’t going to be in big power plants and trans-mission lines. The system’s really going to shift and transform dramatically. Communities are where the energy resources can be located. They’re cheaper, they’re cleaner, and they offer consumers more control over their energy bills and energy choices.” He is, however, disappointed by the backup diesel generator and doesn’t want to see that in future projects.

More important, Sosland points out that canceling the transmission line saved money for ratepayers in all six New England states. Each state’s ratepayers are billed for any project to improve a transmission line’s reliability. But, under current regulations, alternative technology like that in Boothbay has to be paid for solely by the state. The deck is stacked for the old way of doing things. This needs to be fixed, Sosland says. He points out that a heavy investment in energy efficiency by Massachusetts and Vermont canceled more than $400 million in transmission-line work, which would have been paid for by anyone who turned on a light in New England.

Central Maine Power is reserving judgment on the Pilot Project until the full testing period is completed in 2018. “We certainly support the testing of different methods for providing reliable service, which can include alternatives to building transmission,” says company spokesman John Carroll. He agrees that “it’s absolutely the way the industry is going” and that the utility has “a real obligation to look at all types of solutions,” but the company is cautious, keeping its options open. The Boothbay peninsula has only one transmission line, and CMP wants to be convinced that the Pilot Project will be reliable. “It may be an interim solution,” Carroll adds, “and eventually we’ll need to build a transmission line.”

We emerge from the back of buildings to visit Brown’s Wharf Inn. The owner, Tim Brown, whom we flag down while he’s mowing, has gone all in: new HVAC cooling units, solar on the roof, LED lighting. He’s pleased. He’d do more; he only wishes that he’d put solar on his own house when Maine was offering rebates, but he didn’t get to it. The inn came first.

Brown was recently in Germany, where one can see huge windmills next to castles, he says. The Germans have great trains—he’d like to see that here, too. Once you start changing a few lightbulbs, it seems, you begin to see that new things are possible.

I leave Boothbay with one question. This pilot project used less than 1 percent of Boothbay’s rooftop space for solar panels—why not do more?

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Photo Credit : Dave Cleaveland/Maine Imaging

—

After a series of devastating storms, Connecticut passed major legislation in 2011, known as Public Act 11-80, to create a Green Bank to fund “energy resiliency.” Each dollar of state money would be matched by $10 of private investment. In the first year, 11 projects received the go-ahead, but 10 stumbled out of the gate, failing to line up the right financing. Things are now going better. The use of renewable power has grown tenfold. Rooftop solar installations are soaring, while wind was stalled for years as the state wrestled with where turbines should be allowed.

But it’s the planned microgrids that have attracted national interest. A microgrid can stand alone when the rest of the grid goes down; it has enough generators and storage to operate independently. Eleven projects have received funding; three are complete. I’m here to visit the first one, at Wesleyan University in Middletown, driving onto a campus where students, in communion with their smartphones, drift across the roads like jellyfish in the current. They never look up.

I meet Alan Rubacha, a fast-talking, fast-walking optimist who has worked at Wesleyan for 15 years, the last three as director of its physical plant. He’s responsible for about 80 buildings and a small power grid that requires six employees to run. Rubacha offers me some water, and as I’m nodding yes, he disappears, then pops back into the room indicating that I should follow him. In the few seconds it takes me to get up, he’s gone again. Out in the hall, I locate him by following his voice, around a corner and down another hall. He’s on his phone, which he is often. During our short interview, he’s texting and taking calls.

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Wesleyan’s microgrid is a bit deceiving. It was already in place, with the exception of an extension to the Freeman Athletic Center, a 300,000-square-foot building to which was added a big co-generation plant to produce electricity and heat. In an emergency, the athletic center will be a FEMA distribution point. The staff holds drills annually.

The university has been managing its own power system since the 1960s. It added a natural-gas generator in 2009 and is adding solar now. The local utility supplies only one-sixtieth of Wesleyan’s electricity; the rest is generated on campus. The university can “island”: run separately in a blackout. It’s resilient. Wesleyan won the race by starting one foot from the finish line.

Still, these people put it all together, and the world has come to see their microgrid. Rubacha has had visitors from 40 states and as far away as Australia and New Zealand. Even so, this isn’t going to be the solution for most places, he says. Connecticut has been “really forward-thinking” he notes, but “what they found is that it’s harder to do than you think.” It demands an expensive infrastructure. The university is set up to work on that and is committed to reducing energy use, cutting 30 percent in the last five years, while the square footage has increased slightly. The university continues to pursue savings in everything it does, installing things like new windows and more-efficient motors.

So Wesleyan’s system isn’t “the answer”—no one thing is the answer. But it provides an important clue: spurred on by the recent powerful storms, everyone is working on clean energy now. “There’s nothing new in this at all, nothing that’s unique to this, no special technology. It is as simple as simple gets,” Rubacha says of the university’s microgrid. “It’s not a panacea, it’s not perfect, but it’s a step in the right direction for now.”

He asks me about what I’ve seen so far on my yimby tour. “I’m interested to see what it’ll look like in 20 years,” he says. Energy “is going to be way more distributed. I think there’s going to be a power something on every corner, whether it’s PV [solar panels], or a little engine, or a little storage container, who knows what. It’s going to be great.”

—

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Each time I visit Montpelier I’m struck by how diminutive Vermont’s state capital is, as if I were in an HO-scale train layout, but one with locavore dining, organic cafés, brewpubs, and white-collar state and insurance workers in blue jeans and L.L. Bean checked shirts. Montpelier has a soothing rationality. This tiny state capital makes it seem as though no problem is too big.

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

With that attitude, Montpelier has taken on a gargantuan task: to be a “net zero” city by 2030. This, says Vermont’s Energy Action Network, is “a bold, audacious, collaborative effort to have Montpelier lead the way as the nation’s first state capital where all of our energy needs—electric, thermal, and transportation—are produced or offset by renewable energy sources.” But this isn’t a moon-shot crash program; it’s Montpelier-size. The net-zero campaign is run by a committee of volunteers. We do everything with volunteers in New England’s small towns and cities, from putting out fires to feeding the hungry, but getting an entire city to cover all of its energy demands seems impossible.

Tim Shea is chair of the 16-member energy advisory committee. In his day job he oversees facilities at National Life Group, which occupies the largest office building in Vermont (550,000 square feet). The company has converted to a biomass heat plant, saving $400,000 in fuel costs just in the first winter, and added four acres of solar panels to its existing array to provide 15 percent of its electricity. I talk to Shea and assistant city manager Jessie Baker in National Life’s cafeteria, which is far better than it sounds: a pleasant room with high ceilings and sweeping mountain views.

How will Montpelier get to net zero in just 14 years? By taking a thousand, thousand small steps. Each improvement is incremental, and each incremental step is made up of hundreds of smaller steps: meetings, studies, grants, private and public partnerships. You need “day-one savings” to woo the public, Shea says. “It’s hard to dismiss day-one savings.”

As the first steps, Montpelier has installed solar panels to provide 70 percent of municipal electricity at a 15 percent savings over the old utility rates; installed LED streetlights; “weatherized” 500 houses; and replaced a brace of aged oil burners with a centralized biomass boiler system for 21 government and private buildings, eliminating 137,000 gallons of oil annually, Baker notes. These efforts have won the city some national recognition. Montpelier is in the running with 49 other communities for the Georgetown University Energy Prize of $5 million to be awarded next year, and the U.S. Department of Energy has named the city a Climate Action Champion, giving it an edge for certain federal programs.

All of which is encouraging, but Montpelier is just at the starting line. Shea says that the city aims to be halfway to net zero by 2023. Transportation is the high hurdle; it’s nearly 50 percent of energy use. Shea and Baker talk up rezoning to lessen reliance on downtown parking, adding bike lanes, and encouraging car sharing and public transportation. “You can eliminate parking if more people are biking and walking,” Shea explains.

“Have you said that in a public meeting: eliminate parking?” I ask. Having served on a planning committee, I know that parking spots can be revered as holy land.

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Photo Credit : Bob O’Connor

Shea, who drives an electric car, doesn’t hesitate. Look at the city map, he says: “It’s amazing how much real estate” is devoured by parking. That’s land that could be used for taxable development and for housing.

As we were sitting there, gas was at $2.35 a gallon in the city, bringing on a winner’s smugness as people filled up. You have to approach some collapse-of-civilization scenario before you can imagine prying Americans out of their cars—and Vermonters drive more miles each year than most other Americans. (They rank sixth on the mileage list.) Shea concedes that the low price “makes the paybacks harder,” but he’s steadfast, talking about finding the right mix of “carrot-and-stick” programs to move the stubborn-mule public.

Montpelier was able to add its solar panels and biomass boiler without expending any of the city’s tax dollars. But to achieve the committee members’ goal, won’t they eventually have to spend the city’s money? They firmly say no. Montpelier has a high tax rate, Baker explains, with a population of about 7,800 having to provide services for up to 20,000 each day. She hears from residents who are concerned about “how to balance this audacious goal against the financial realities of our municipal budget,” she says. A good case can be made for the long-term benefits, but she knows that “there’s some fear in the short term” about taxes.

To get to net zero, Shea says, “a lot of this basically comes down to behavioral marketing.” There’s strong support from Mayor John Hollar and a core of committed citizens. “We just need to keep pushing that 80 percent in the middle to help us get there.” Mont-pelier could be a demonstration project for Los Angeles or Seattle or Chicago, he adds: “Now, they’ve got their own things going, but with a lot of what we’re doing for a northern climate, we can really become the pilot poster child for—this might be a little grandiose—a national movement.” Other places large and small can learn from what people are doing in Mont-pelier, he says.

Striving to be a net-zero city appeals to old New England virtues: It’s pragmatic, it’s thrifty, it’s the right thing to do, and it plays to the region’s pride in independent thinking. “Resiliency” is the buzzword of this new energy movement, and in that word is an echo of another old New England virtue: self-reliance. “Our residents have this culture of being innovative, being progressive, being willing to try things,” Baker says. “The size of our community lets us perhaps do some ambitious things a little more easily. We know each other. We go to church together. We go to soccer practice together. And it kind of contributes to that Vermont way of doing things.”

—

Will this work? Can we patch together enough solar panels, efficient lighting, and generators to tame our energy hunger? Can we do enough quickly enough to slow the planet’s warming? That’s what this is really about. We’re on a roller-coaster ride of ever-wilder storms and hotter summers. My short yimby tour is encouraging, showing how we can swiftly change things, but I may be cheering a short parade.

When you see these new ways of doing things, it’s freeing. It’s as if you were hearing long-stuck machinery moving. But then you leave these new projects and head into the gas-and-go haste of how we’ve done things forever, and the fossil-fuel present seems iron-bound and eternal, “ a fate … that never turns aside,” as Thoreau said of the technology of his day.

What’s holding us back isn’t technology, and not even the old regulations, though those have to change. What’s holding us back is that we don’t believe we can change things. In a region once renowned for its mechanical literacy— for backyard tinkerers filing a flood of patents for improved water turbines, steam engines, early automobiles and airplanes—somehow we’ve lost our belief in Yankee ingenuity. Of course there still are many can-do inventors, designers, and builders among us, but, lacking millions of dollars for advertising and lobbying, they can be lost in the noise.

—

I have one more stop to make before I leave Vermont. I drive a half-hour south of the capital to visit someone who has been at this solar thing since he was an architecture student in 1970. I go see architect William Maclay at his Waitsfield office. Recently he wrote the definitive book, The New Net Zero, a hefty 552-pager giving many successful examples and extensive construction details for houses and large commercial buildings.

“We’re not in the world we were in 10 years ago,” Maclay tells me. “For me, an advocate for doing solar for 40-some-odd years, to say that I can live on less money with solar than I can with fossil fuels is just a radical change. And it’s a radical change that 2 percent of the population realizes.” People don’t know that they can afford solar, that they can afford net zero, he explains.

He sets out the numbers: For solar panels there’s a 30 percent rebate off the top from federal tax credits; historically low loan rates; and plummeting solar-panel prices, which are 75 percent lower than they were a decade ago. It’s cheaper to install solar than to keep paying for oil, Maclay says: “Renewably powering your electric bill is cost-effective today. That’s just huge. It’s never been that way before. You can hop onboard and save money and do the right thing at the same time. Climate’s an issue; there’s no excuse not to be addressing that. [This] isn’t some weird technology we have to wait for. It’s here today.” This isn’t your hippie uncle’s solar energy.

“Will Montpelier succeed?” I ask.

“I think they’re going to get there, and everybody’s going to get there, or we’re not going to be around,” Maclay replies. And with that we adjourn to look at the small tan boxes outside his office and an adjoining house (heat pumps) and the gray boxes in the basement (a solar-power inverter). They’re not much to look at, either, but they may mean the world.

Thank you for a great article. It is inspiring to hear these smart, New England people, companies and organizations are leading us into the future. Hopefully these great New England minds will be able to influence the FERC and those clinging to the old, centralist energy infrastructure.