Nantucket Beach Erosion | A Disappearing Island

On a Friday in mid-October, Eugene Ratner takes stock of the churning sea in front of his home in Nantucket’s Madaket region, on the island’s southwestern shore. “This is bad,” he says. High, white-rimmed swells break and slam a few feet from where he’s standing, sending up a salty spray. “This is what you see […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Smith, Dana

On a Friday in mid-October, Eugene Ratner takes stock of the churning sea in front of his home in Nantucket’s Madaket region, on the island’s southwestern shore. “This is bad,” he says.

High, white-rimmed swells break and slam a few feet from where he’s standing, sending up a salty spray. “This is what you see in winter.”

Photo Credit : Smith, Dana

Bad, but not surprising — not on this island, just 25 miles off Cape Cod and exposed to the ocean’s forces. Ratner knows that as well as anyone. He started summering here regularly in 1975, when he and his wife, Roslyn, built this house, a large five-bedroom saltbox with an expansive view of the sea. There were few neighbors back then, and a lot more beach.

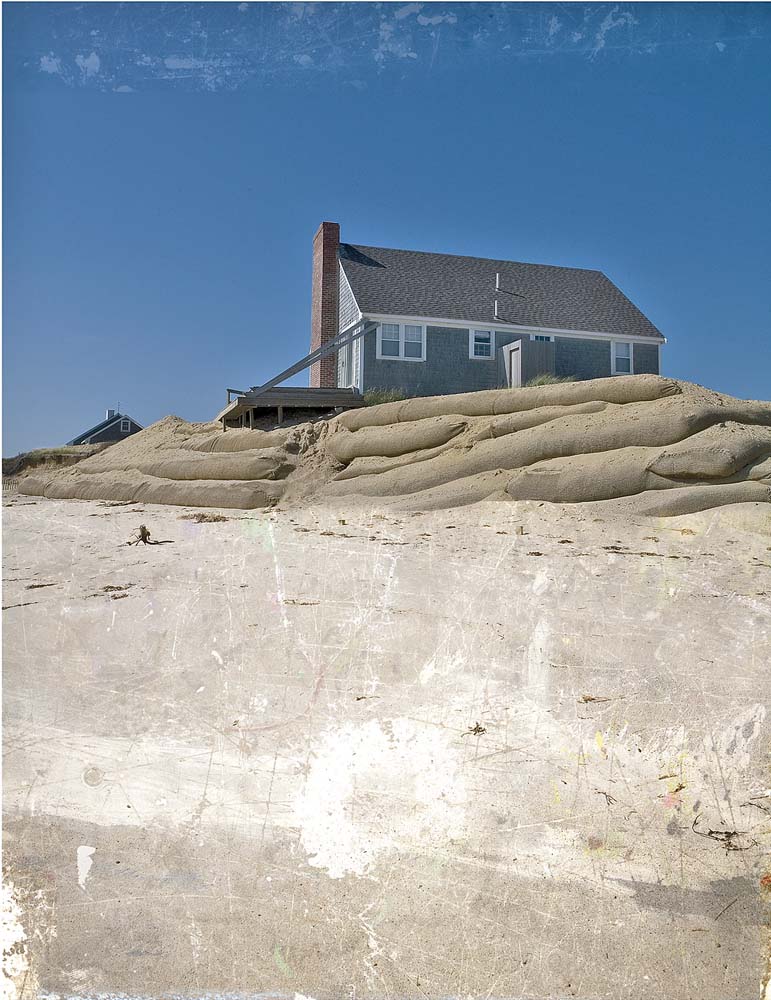

Today, his home survives defiantly in an area where the erosion rate currently averages 12 feet a year, the highest rate in Massachusetts and maybe in the Northeast. The evidence of that is everywhere: in nearby lots whose homes have been moved or lost to the sea, in the abandoned section of road that continues on past Ratner’s property before disappearing into the sand, in a forgotten concrete sewage tank that sits smack in the middle of the beach. Ratner estimates he’s sunk $500,000 into saving his home, armoring the front and sides with enormous geotextile bags filled with sand — hundreds of them, weighing many tons apiece, forming a wall that runs 45 feet deep, 20 feet of which is visible above the water surface, dividing building from ocean.

“We’re trying to build the Hoover Dam,” Ratner jokes.

Still the ocean comes. Maybe 20 feet separates the building’s foundation from the outer edge of the bags. Temporary walls of plywood and pressure-treated posts protect the driveway and plants from sand drift. Ratner’s place looks more like a fortress than a dam.

When he first noticed he was losing land, in the early 1990s, he wasn’t alarmed; 100 feet of grass, 30 feet of dune, and another 30 feet of beach separated his house from the sea. But shifting shoals and storms gnawed away at all that protection. Having already lost a deck to the surging ocean, Ratner began dropping the first set of bags in front of his house in 1995. “My wife used to complain that we couldn’t see the water from our first-floor bedroom,” Ratner says. ” ‘Why did you build the house so far back?’ she’d ask me. Well, it’s a good thing we did, or we’d have lost it by now.”

It’s an old story. Land and homes have been lost to the sea for generations on Nantucket, a 48-square-mile patch of sandy earth, deposited by a glacier, that became an island when the ice melted and the seas rose around it more than 10,000 years ago. It’s why native islanders have often shied away from the coast when building their homes, or placed them on movable skids if they built near the sea. “Erosion is just something we live with,” says one islander. “You gotta realize that sooner or later the water is going to come visiting.”

But that’s not something that Ratner and other wealthy summer residents who have scooped up valuable, but vulnerable, waterfront property over the years are prepared to concede. That battle with nature — a confidence in the belief that determination, technology, and money can restrain the elements — is an old story, too. As is the outcome. In recent years, millions of dollars on this island have washed out to sea.

The relationship between homeowners like Ratner and town officials out here hasn’t been easy. Nantucket has some of the most restrictive building codes on the East Coast. Hard structures, like seawalls, which line much of the Cape, have largely been banned since 1983. On the south shore, the Conservation Commission has kept a tight leash on homeowners like Ratner whose ideas for saving their houses have consisted of anything other than finding new locations. “There’s no love lost,” Ratner admits. He sued island officials when they denied him permission to use an even larger sand-saving technology called Geotubes.

“[These bags] aren’t a cost-effective method of erosion control,” he admits, standing in his driveway. Nearby, his handyman is nailing sheets of geotextile fabric on a wall of plywood in front of a garden of hydrangeas.

“But there’s nobody with a view like what I have here. In the summertime it’s unbelievable,” he adds. “The house is up — what are you going to do, just walk away and let it go into the ocean?

“I told the town that I’ll be here until I’m dead, and I’ve followed that. I’m not going to get wiped out, but the road will. I’ll lose my electricity and then I’ll be an island. If that happens, I’ll just go get a generator.”

Across the island, Nantucket’s ‘Sconset Beach stretches out, a narrowing, often empty strip of sand that helps form the eastern bend that defines the shape of this island. It’s a summerlike fall day, and flat waves lap their way toward the bluff. At the base of one particular section, a small crew of workers builds a wall of sand-filled jute bags, each measuring half a football field long. It’s a mini–construction zone, with tractors moving earth and dumptrucks unloading sand from atop the cliff. But it’s just a stopgap measure, something that will only delay the ocean’s attack. Over the coming winter, this crew will be out here repeatedly to repair what the water has done.

It’s pushing three o’clock and the men are getting ready to go. Two of them, Manuel and Juan, both from El Salvador, take a moment to assess the day’s work. “Seven years I’ve been doing this,” says Manuel. “We do the same spots over and over.” Just then an anxious Juan says something to his friend in Spanish. Manuel turns back and points to his wrist, pretending he has a watch. “We have to go,” he says. “The water is coming.”

And with that, the two scamper up the steep cliff, at times using their hands to claw upward, before a final ascent over the bluff’s bowed-out top section, where they disappear.

Here in Siasconset, or ‘Sconset as it’s known locally, homeowners aren’t fighting just the sea; they’re fighting their neighbors, too. At the center of this battle is a collection of some 50 lavish houses on Baxter Road, a quiet seaside street that dead-ends at Sankaty Head Light, to the north. Perched high on a sandy bluff with commanding ocean views, these homes, with names like “Luke’s Lair” and “East of Eden,” are the part-time addresses of people who’ve made their fortunes off-island. For the past 15 years, wind and waves have been shearing off the bluff and, for some folks out here, necessitating an expensive retreat from the water as homes are jacked up and moved to safer ground.

Millions have been spent on erosion research and mitigation work, too, with a good chunk of that money coming from the wallet of a tall, lean 71-year-old, a retired commodities trader named F. Helmut Weymar. Weymar, who lives in Princeton, New Jersey, has entrenched himself in erosion battles over these past two decades with a doggedness that has earned him the local nickname “the Determined German.”

“It’s the single most time-consuming part of my life,” he says. I’m visiting Weymar on a stunning afternoon, when his place is abuzz with the sounds of saws and scrapers as carpenters repair a front porch. His home, which he and his wife Caroline bought in 1987, is a gem, a five-bedroom Colonial Revival with weathered gray cedar shingles, crisp white trim, and a widow’s walk adorning the roof. “Tallest house in the neighborhood,” Weymar says, lightheartedly.

But today, as on most days, his eyes are directed to what’s below. Out back, where perhaps 25 yards separates his house from the edge of the bluff, a narrow row of beach roses lines the back edge of the lawn — a final show of vegetation before the land drops sharply into a steep sandpit wall. In the distance a motorboat zips along the water; fishing boats dot the horizon.

“This bank right here was fully vegetated with about 200 feet of dunes before you got to the beach,” Weymar explains. “We had a walkway that went down there, and the yard went out another 10 feet.”

Like many homes along the bluff, Weymar’s was the creation of forward-thinking developers of the late 1800s who realized that ‘Sconset, a sleepy fishing community turning summer destination, needed more prominent residences than village shanties. Their homes featured expansive lawns separating each house from the bluff, with a public right of way. That’s why, even today, it’s perfectly normal to see strangers traipsing through the backyards out here as they follow mile-long Bluff Walk, which itself is eroding.

Weymar still enjoys walking the trail, in part because it’s like going back in time. To the south the beach is wider, the dunes still present, and the cliff’s gradual slope is covered with roses. Farther north, it’s a different story. With few dunes or shoals to stymie its energy, the ocean batters the bluff’s toe, strips away sand, and destabilizes the cliff. Big storms can bring disaster. In 2005, winter storms carved off 25 feet of bluff in less than a month and forced one homeowner to slice off the piece of his house that was hanging over the cliff. Over the past several years, a dozen homes on this road have been moved back or relocated.

Weymar’s house been lucky: It still sits on its original 1916 foundation. But nobody has to remind him of what he’s up against. Along with the scientists he’s hired, he’s made a careful study of the water and the land, familiarized himself with practically every erosion-fighting method available, and founded the Siasconset Beach Preservation Fund (SBPF), a nonprofit with more than 400 contributors, dedicated to addressing the community’s erosion issues.

Today ‘Sconset Beach is a reminder of lost battles. The mechanically doomed pumps and valve stems from a huge dewatering system that was supposed to lower the beach’s water table, and remnants of temporary terracing projects whose bags and posts storms have tossed about like little toys — they’re all in plain sight, $15 million in research and labor to fight the inevitable.

Even here on Nantucket that’s a lot of money. “It’s just stubbornness and arrogance on their part, because they have money, so they think they can outsmart Mother Nature,” says one ‘Sconset native. “That’s the risk you take. I wouldn’t have bought property on an eroding bluff, but that’s just common sense to me.”

Still, the money comes. Since 2005, SBPF’s newest target has been a $20 million beach-nourishment project that would dredge the equivalent of some 200,000 dumptruck loads of ocean sand and pump it onshore to build out ‘Sconset Beach — ultimately, its proponents contend, protecting the bluff and the houses. The idea behind it is this: By building back the land, in this case extending a roughly three-mile section of sand 150 feet out into the water, you hold back the ocean. Essentially, two beaches are created: a sacrificial one to feed the sea, and a permanent base behind it.

In effect, nourishment tries to tap into the complex system of give-and-take that defines any beach. Simply put, the ocean moves sand from one location to another — the direction varies according to the currents — through a process called littoral drift. Waves wash up onshore, deposit material, and then fill up again with material as they recede. But the harder the water rolls in, the more material it extracts and the less it leaves behind. And that’s what’s happening in ‘Sconset, where a high traffic transport of sand — the equivalent of about 20,000 dumptruck loads of the stuff — moves through the water each year.

Creating nourished beds, however, involves six months of around-the-clock dredging and vacuuming sand from the ocean bottom, while the slurry is pumped through underwater pipes onto the beach and bulldozers move and shape the material. The life expectancy of the sacrificial portion of a nourished beach is just three to five years, which means that ‘Sconset would be looking at a permanent cycle of renourishment and the costs that come with it.

But although the SBPF homeowners would absorb the financial hit, year-round islanders say, Not so fast. How will nourishment affect fishing and wildlife? How will it affect neighboring beaches? Where will all this sand go once the sea gets ahold of it?

“They like living there, but I don’t think it’s just about protecting their houses,” says Dirk Roggeveen, administrator of the Conservation Commission. “I think Helmut and others putting up the money are really just interested in the challenge: Can you stop the process and can you do it in a way that’s environmentally responsible? And if there’s damage, can you mitigate it?”

Weymar dismisses any notion that hubris is behind the proposal. “We’re not talking about rocket science,” he says. “It’s been done hundreds upon hundreds of times all over the globe.” Still, Weymar has made one important precautionary move: A few years ago he bought an empty lot across the street. Just in case.

“The homes here are cohesive,” he says. “People say, Move the houses. Yeah, right. One here, one there, scatter the place around versus [preserving] this integral, incredibly precious and valuable historic architectural resource that we’ve got now. If you do the 100-year projection of long-term erosion rates, it’s going to go. The shorefront will be in the middle of ‘Sconset Village.” Weymar is still standing in his backyard. But now, instead of facing the bluff, he’s wheeled around toward his home. “All these houses will be gone.”

Photo Credit : Smith, Dana

A prediction like that doesn’t surprise Josh Eldridge. He’s 34, with a mop of dark hair tucked under a weathered baseball cap. Eldridge is driving his tired-looking truck, with a sticker that says, “The Mate Works for Tips,” slapped on the back bumper. Eldridge, a ‘Sconset native who now lives in Nantucket Town, is headed back to his home turf for a visit.

He may not live in ‘Sconset anymore — “Can’t afford it,” he says with a laugh — but his family connection to the village goes back four generations. There’s even a road there named after them.

As a kid, Eldridge often rode shotgun in his grandfather’s dumptruck, helping out as his granddad made the rounds collecting residential trash. “We’d be up on North Bluff — and this was like ’76 or ’77 — and he’d be looking at those big homes going, ‘Yep, one day these things will all be gone,'” says Eldridge, in between gulps of ginger ale. “Everybody knew it then. This erosion is not a surprise. Everything disappears. The tides are rising. It’s gonna go away.”

Like many year-round residents here who aren’t packing trust funds, Eldridge is a lot of things: real-estate broker, mechanic, carpenter. But fishing is what defines him. And in large part it defines the position he takes on any massive operation to control erosion. As it’s proposed, SBPF’s beach-nourishment project would have a direct impact on what Eldridge and others who make their living at sea say is a prime but delicate fishing resource: thousands of acres of cobble through which bass, flounder, bonita, and bluefish, among other species, pass at various times of the year to feed on squid, lobster, sand eels, anchovies, and crab.

Still in his truck, Eldridge weaves around the small rotary at the center of ‘Sconset and then down into Codfish Park, a flat area of beach, dunes, and little former fish shacks that have been prettied up as summer rentals. Eldridge parks and hops out. “Let’s go for a walk,” he says. He slips off his sandals and begins making his way through beach grass and dune, toward the water. About halfway there, he stops, raises his right hand, and points to the sea, sweeping his finger across the horizon.

“This is the hot zone,” he says. “It’s maybe one of the top three most important pieces of bottom in southeastern Massachusetts. When people look for big fish in big numbers, they come to Sankaty. The guys from Chatham, they could go anywhere in Cape Cod Bay, but they decide to come here. I’m not trying to downplay the situation. [The homeowners] would be screwed. I’ll feel bad for their summer houses, but I’ll also feel really bad if my fishing business goes to crap.”

That cobble will be destroyed isn’t up for debate. Between the dredging work and the heightened littoral drift that will result from giving the ocean more material to feed on, SBPF’s own scientists have predicted as much, prompting the group to offer compensation for lost wages and a project to re-create the destroyed habitat. What’s contested is the estimated amount (105 acres) and its significance. Even a minor shift in the quality of hard bottom along these waters could have a detrimental effect on an island where the last vestige of a once-great fishing community is now an overcrowded charter industry.

Which is another way of saying: This story is about more than just sand and water. It’s about identity: about who’s going to have a say over the very force that built this island up and now in another form is in the process of taking it away. To locals, a project like SBPF’s is a brazen display of wealth that violates the code of adaptability that’s required to live in such a vulnerable environment. It’s another signal that Nantucket no longer creates fortunes — it just attracts them.

“We’ve changed from a tourist destination to a place for summer residents,” says longtime fisherman Bobby DeCosta. “Fishermen don’t have the clout they used to. Merchants don’t, either. Teachers, department heads — regular people can’t afford to live here. I really wonder what this place will look like in 10 years.”

Eldridge wonders that, too. He’s back in his truck, taking a slow spin around Codfish Park. In the early 1990s, a series of nor’easters rolled in, eating up close to 200 feet of beach and dune. Even more dramatic was the toll it took on a row of beachfront houses, forcing their removal, and in one unforgettable moment taking one home out to sea before dispensing with it. A few of Eldridge’s childhood friends lived in those houses, and he slows his truck down to a crawl as he nears their former sites. “It’s so weird,” he keeps saying.

On the road out of Codfish Park, he stops and motions to a tall cedar-shingled house just to the right. On its side is a sundial that his father, a local volunteer fireman, rescued years ago when the building that had stood here burned to the ground. When the home was rebuilt, Eldridge’s father surprised the owners with what he’d salvaged.

“It’s little pieces that make up the whole community,” says Eldridge. “I’m not trying to belittle the homeowners up on the bluff; their memories of ‘Sconset and their lawn parties and everything else are very important. It’s all part of the tradition, and memory, and history. Unfortunately, some board somewhere has to make a decision as to which is more important — whose memories are more important, whose way of life is more important.”

On a late afternoon in autumn, a modest assortment of residents, town officials, and outside consultants file into a small auditorium in Nantucket High School. The meeting, a public hearing between SBPF’s hired team of engineers and scientists and the seven-member Conservation Commission, is the third of many. What the commission decides will determine how and when the Baxter Road residents may move forward to secure local and state permits.

That’s assuming, of course, that the nourishment project even happens. High respect for nature on Nantucket is matched by an equally skeptical view of any attempt to manipulate it. “It’s sort of an old battle,” says Peter Brace, a reporter for the Nantucket Independent. “[Out here] we’re so close to the elements and so close to the ocean and the environment that we’re all environmentally aware. Everyone has an opinion.”

That certainly extends to the ‘Sconset project. On this night, unconvinced residents fire away at the SBPF team. The largest contingent consists of Josh Eldridge and a dozen or so other fishermen, who sit in the back, with arms folded, as they take turns castigating SBPF on its fish-research methods and projections. “At the end of the day,” one fisherman says, “you only came up with the worst proposal.” Their reactions mirror those of most year-rounders, who argue that the logical solution is for the homeowners to just move their houses.

“[We’d] be the immediate beneficiaries of this, but the long-term benefit [would be] for the island,” counters Sam Furrow, who recently paid $200,000 to move his second Baxter Road home. “We protect every other element of the island, but we’re ignoring the shoreline. People say our effort is wrong, but to preclude this effort is very shortsighted if your true love is Nantucket and your intent is to pass it on to people better than you received it.”

But if the scientists are right, if the sea levels continue to rise incrementally and storms become not only more frequent but also more powerful, maybe the only thing Nantucket property owners can do is allow nature its destiny. Jim O’Connell, a coastal geologist for the Sea Grant program at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution on Cape Cod, believes that Nantucket’s fate is sealed. “I did a lecture out there last year,” he says. “I showed aerial and ground photos and talked about what I was seeing and what the data showed. I began with a picture of the open ocean and announced, ‘In 8,000 years this will be your island, and until you get to that point, every house is going to enjoy a spectacular ocean view.’ I got only a few chuckles.”

Photo Credit : Smith, Dana

Last March, I returned to Nantucket for the first time in five months. Despite the deep-blue sky, the winds howled and white curling waves made their way toward the island. It had been a long storm season. The south shore in particular had taken a pounding, thanks to a devastating bout of weather in early November that brought 87 mph winds and four inches of rain. In the Madaket area, 16-foot swells had wiped out up to 20 feet of shoreline in some spots.

The most extreme wreckage was on display at the end of Massachusetts Avenue, a bumpy dirt road, lined by several small cottages, that empties out onto the beach. There, a few larger homes at the end of the street had been moved back, onto temporary foundations of steel I-beams and wooden cribbing. Next to one, a ranch aptly named “Breaking Away,” the carnage of its former setting — decking boards, old staircases, a septic tank — littered the ground. On nearby Rhode Island Avenue, people were preparing to move another house for the second time in a year.

Although Eugene Ratner’s house was doing fine, he’d still need to do some work. His wall of bags had sunk a little, and a few had even emptied and floated out to sea, prompting a warning from the Coast Guard. Across the island, in ‘Sconset, things looked a little better. A Baxter Road house that had been lifted up on jacks now sat safely on a new foundation, while a few houses south, Helmut Weymar had planted a new row of beach roses in his backyard.

A few weeks later, the exact degree of opposition to the proposed nourishment project was revealed, when voters came out overwhelmingly against it, 2,986 to 483, in a nonbinding ballot vote — and also decisively supported a temporary moratorium on any kind of large coastal project until island officials have put together a comprehensive coastal-zone management plan. The deadline: end of 2010.

The outcome caught the Baxter Road homeowners — who had lobbied the public with a polished documentary and slick-looking postcards that read, “I want my kids to enjoy ‘Sconset Beach just as I did” — by surprise. Their argument, after all, had been a sort of “what’s good for ‘Sconset Beach is good for the rest of the island.” But a simple reading of the tea leaves told them all they needed to know; despite nearing the end of its sessions before the Conservation Commission, SBPF withdrew its proposal in early May.

Opponents of the project, like fisherman Josh Eldridge, followed up their sudden victory with both a willingness to help SBPF find a more agreeable solution and some concern over what the group’s idea for a new erosion fix might just be. “[Killing the proposal] is going to help them out with the island right away. They do have a problem,” says Eldridge. “But look, you’re dealing with a lot of old Yankees out here, and so after they withdrew, a morbid dread kind of set in — a feeling of What are they going to do now?“

Just exactly what the ‘Sconset homeowners are going to do is uncertain. Weymar says he hopes that SBPF can help the island create the coastal-zone management plan so that residents can vote on it at next year’s Town Meeting. If that happens, it’s possible, he says, that he and others will have regrouped enough by then to put together a new proposal for combating erosion as well. But they’ll have to contend with the hangover from this most recent defeat first.

“There’s been a lot of talk about working together, and I’m going to take it at face value, but my confidence is marginal that we can find a solution that’s acceptable to everyone,” predicts Weymar. “We didn’t expect this level of opposition. It was too technical, and it got quite emotional — people claiming environmental catastrophe. But I do think we raised the consciousness that erosion is an island-wide problem.”

Maybe.

Around the same time that SBPF was making a move to withdraw its proposal, builders, in a curious display of optimism, were putting the finishing touches on Baxter Road’s newest home, not far from Weymar’s house. Nearby the tide was moving in, and the water was taking aim at its target.

Yankee wants to hear from you! Submit your comments below.

Read more about Cape Cod’s shifting shoreline and follow a link to historic maps: Nantucket’s Shifting Shoreline

hello, read the article on the erosion problem in nantucket,im afraid there fighting a losing battle,and that mother nature will prevail, i for one would like to see a moratorium on any more building on the coast? other than state and federal parks so everyone can enjoy the coast,i remember when they ran the poor portugese fisherman out of new bedford and put in dockominiams, for the select few that could afford them,wazzup with that? gloucester and cape ann is starting the same thing, owell tyme will tell i imagine cheers chet ps i love your magazine

I will never understand the building of homes and the thought process of government leaders/elected officials that allow these actions to take place.the New England way of life is disappearing fast.As a recreational fisherman I can empathise with Mr.Eldridge and others who appreciate the wondrous beauty and the bounties that nature has to offer.Ecological destruction,let’s be honest, that’s really what it is, on the coastlines and inland in forests change this planet forever.I am amazed at the silence most times of environmental groups,some of which I am a member and/or contributor to.I wonder at times when I see mansions or developments built what contributions were made by these folks to environmental groups for there “silence”.Pristine coasts and forests where access was available to all,shut out forever for the few to enjoy.People have a right to develop their land but that right stops with me when it becomes a detriment to others.But what do I know.I am not a bleeding heart liberal or right wing.I am just a working stiff who is amazed at the wonder and power of mother nature everytime I go to the sea and forests to fish or take a walk.i pray the stripers are there 100 yrs from now in ‘sconset for all to fish and enjoy and the cobble not destroyed for the sake of a house.