Mirna Valerio | Blazing a Trail for All to Follow

Meet Mirna Valerio, the inspirational Vermont-based trail runner who is helping pave the way for all to enjoy the outdoors.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan

Photo Credit : Christian Blaza

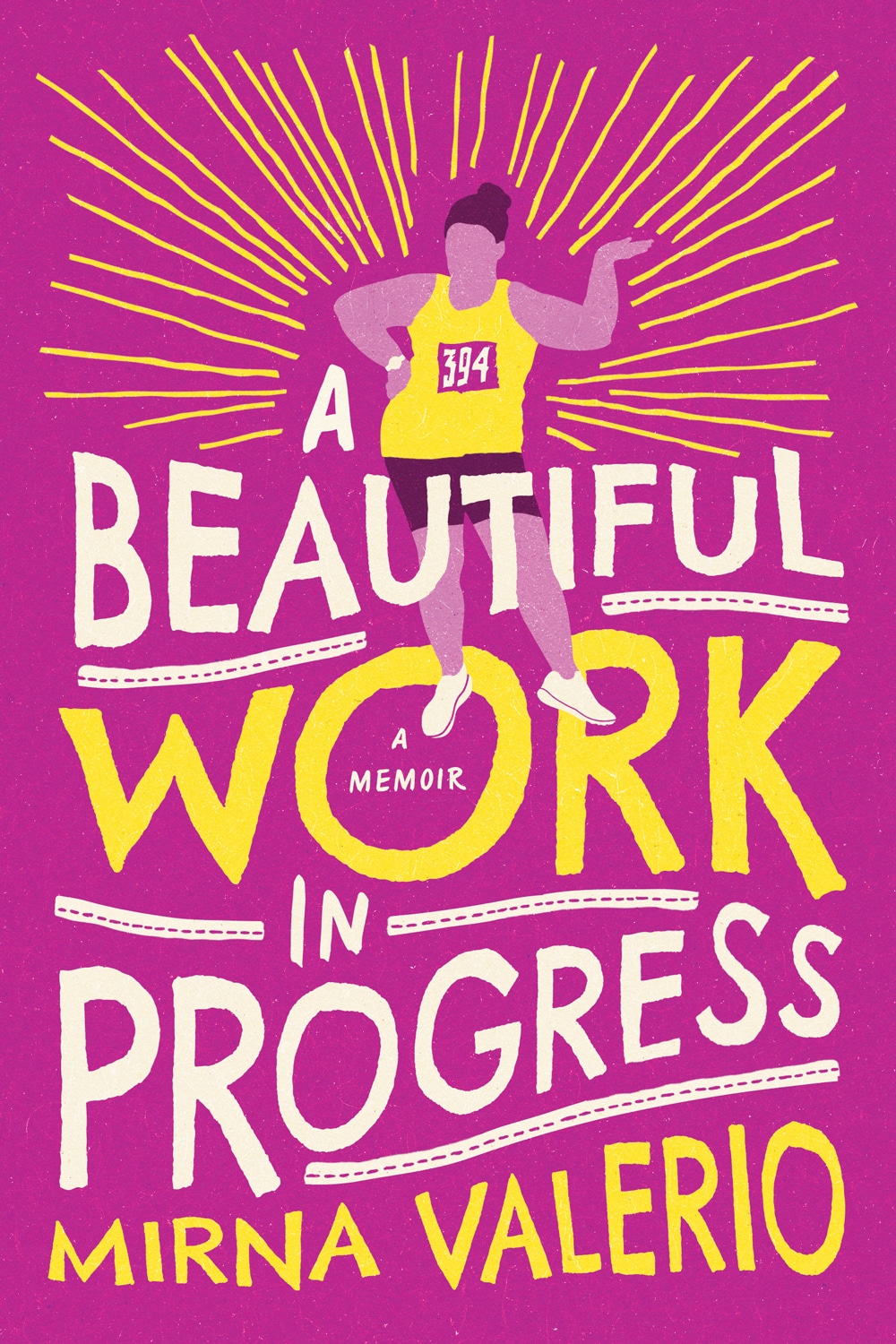

In her 2017 memoir, A Beautiful Work in Progress, Mirna Valerio circles back in varying degrees to two important questions: Why not celebrate your body? And why not be proud of the fact that the one you are in can do great things?

A 2008 health scare put Valerio on a path toward discovering her own potential. She was working overtime as an educator and a mother when a severe panic attack forced her to confront how she’d allowed her well-being to spiral downward. Her doctor asked her: “Do you want to see your son grow up?”

So Valerio started running. A little. Then a little more. A few months in, she completed her first 5K. Bigger races followed. In the fall of 2011 she ran her first marathon. Two years later, she completed her first 50K. To date, she’s finished 11 marathons and 14 ultras, which have included some of the most grueling trail races in the country.

Photo Credit : courtesy of Mirna Valerio

“I just want to see what my body can do,” says Valerio, now 45. “I want to know what the limits are.”

But this Brooklyn, New York, native is also pushing against other limits. Her message and her accomplishments are a rebuke to an outdoor culture that is mostly white and obsessed with body types that don’t look like hers. A decade ago, Valerio started a blog called Fat Girl Running, which broke hard from topics for a diet-obsessed crowd with posts such as “Calling BS on BMI” and “How to Be a Fat Runner in 10 Simple Steps.”

Since then, Valerio—aka the Mirnavator—has built a national profile that amazes even her. In 2017, she landed on the cover of Women’s Running. In 2018, National Geographic named her one of its Adventurers of the Year; that same year, actor Will Smith hired her to train him for a half marathon.

At the beginning of 2019, she moved with her teenage son, Rashid, to Montpelier, Vermont, so she could have a “beautiful place” to train as she embarked on a full-time career as a sponsored athlete for brands such as Lululemon, L.L. Bean, and Merrell, among others. Today, her Instagram following is well into six figures.

We met for breakfast last fall in downtown Montpelier, and during our time together she laughed freely and often at the improbability of her journey. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Photo Credit : courtesy of Mirna Valerio

Ian Aldrich: What’s your earliest memory of being in the outdoors and in the woods?

Mirna Valerio: I went to sleep-away camp when I was 8, the summer before third grade. My stepfather’s union had this program where kids from the five New York City boroughs could go to the Catskills. Going to this camp, it’s the single biggest reason I do what I do now.

I.A.: Wow. What was its impact?

M.V.: There was all this buildup, buying all this outdoor stuff—we didn’t know what we were doing. We bought Timberland boots, the early versions, and jeans, and we bought a sleeping bag that was all cotton, of course. Nothing was high-tech. I got on the bus and we sang songs on the way there, you know, the way they do to invite you into the outdoor cult. [Laughs.] And then that first night I went on this stream hike. It was terrifying but cool, just being in the dark. We stopped in this huge culvert, and I remember how scary and noisy it felt—the water running, the echoes of our breathing, the crickets outside. Then the counselors gave us Wint-O-Green Lifesavers, and there we were: in this big pipe with sparkling green lights coming out of our mouths.

We were all strangers to one another, from different schools and different kinds of families. But we were all kind of nervous, I think, and that brought us together. It was the first time, outside of being with my family, that I felt socially OK.

I.A.: So you’re building up confidence in yourself too.

M.V.: Exactly. I loved the water, but at camp I only liked hanging out in the lake where it was three feet deep. There was a little dock, and on the other side it was six feet, and I’d always say, “I’m glad I don’t have to go over there ’cause that’s scary.” Well, one of the swimming instructors heard me and said, “Guess what you’re doing today?” I freaked out. But she said, “You know what to do. You’re just going to do what you do here, over there. Don’t touch the ground, and let yourself float.” I was scared but I was fine.

I think about that all the time, when I know there’s another level I can achieve and I think to myself, I’m glad I don’t have to do that. [Laughs.] Well, here’s your lucky day. I just make myself do it.

I.A.: You’ve run in a lot of grueling races. How do they force you to reckon with yourself?

M.V.: It’s such a mental game. I know that physically I can do it, or that I can at least try. And part of my mental game is dealing with all the internal pressure and the external pressure to beat the cutoff because I’m slow. So, it’s about not being attached to the outcome even though it is important to me to finish what I’ve started. It’s a lot of internal work to be Zen about whatever happens.

I.A.: It’s like a long meditation.

M.V.: An hours-long meditation!

I.A.: How does that translate into your broader life?

M.V.: Right now, during Covid, there’s so much uncertainty. It’s unprecedented. It’s a long slog. It can be the same with a long race. You’ll be in the middle of an ultra or even a 10-miler, and you just feel like it’s never going to end. At some point it will, but not now. And you just have to keep going, doing the things you know you have to do. You need to keep moving forward. You need to keep eating and drinking. You need to keep yourself busy. You have to find a way to keep yourself engaged, because the minute you lose focus, the minute you aren’t engaged, something bad happens. You trip. You fall. You may get hurt. I can’t help but bring that to the rest of my life in order to get through the times we’ve been having.

I.A.: Do these big races also help you explore something about yourself?

M.V.: I want to know how long I can go. How long I can keep moving. I just want to see what my body can do. Even I have preconceived notions about what my body can do. I want to know what the limits are.

When I signed up for my first and only 100K, it had been a thought floating around in my mind: Can I do this? Nah. But I’d done a bunch of 50Ks, and it was the next thing. That’s how I got into marathoning: I can’t do that. But I know I can. Then a friend comes along and asks, “Do you want to do a marathon with me?” Now it’s a 100-mile race. I know I have to do one. I gotta see. I’m curious. Maybe I won’t be able to finish my first, but I’ll learn something from that. I’ll learn how to train and I’ll try it again.

I.A.: Let’s talk about your move to Vermont. Was there any commentary from friends or family about that decision?

M.V.: Yes. Why are you moving there? You know it’s like the third-whitest state in the country, right? I’m like, I know, but I need to train. And I’ll tell you, I felt at home right away. The first night I drove down Main Street in Montpelier, I saw a Black Lives Matter sign and a Pride flag. Having lived in north Georgia for the previous five years, where it’s beautiful but very conservative, I wanted to live in an area that was more progressive. Even now, every time I drive into Montpelier, I have this feeling of I really like this place. And my son likes it. He feels safe. He feels very empowered to just go out and do whatever he needs to do for himself. I like that, and I don’t think we could feel like that in Georgia or even really in New York.

I.A.: Do you have a go-to spot in the state where you take family and friends when you want to introduce them to Vermont?

M.V.: Depends on who the family and friends are. [Laughs.]

I.A.: Or just for yourself, then.

M.V.: I love to go to Mount Hunger here in Montpelier. It was the first mountain I did in Vermont. It’s not the prettiest. It doesn’t have the best views. It’s really difficult. But there’s something about it that keeps pulling me back. My friend who lives in Barre and is the reason I decided to move to Vermont brought me up there in December 2018. It was my first time in Vermont and the first time I’d been on snowshoes. We went up the mountain and it was the most spectacular experience. There was maybe one or two other hikers up there. It was all snowy white and I’m thinking, This is a Robert Frost scene right now. It was just so still and quiet. At one point we went across a stream that was all iced over. You couldn’t see the water, but you could hear it. I just felt like, This is where I need to be.

I.A.: You’ve become such a strong voice in the body positivity movement. Why do you think your story and who you are have resonated with people the way they have?

M.V.: I think there are a couple of reasons. I think that people have these ideas of what this [motions to herself] can do.

I.A.: Being a Black woman?

M.V.: The bigness and being a Black woman too. But I’ve always come up against that in every aspect of my life. People look at me as a Black girl—What’s she doing in the gifted class? I hear it and I see it. But I continue to do the work because only I know what I can do. You don’t know me. You don’t know anything about me. You’re making these assumptions about who I am. It’s been like this since elementary school. I think a lot of people would be hampered by other people expecting lower of them or expecting them not to be able to do something because of the color of their skin, the shape of their body, or their gender.

I.A.: Does it get exhausting to have to explain your presence all the time?

M.V.: Absolutely. People think they know why I’m fat. Just this morning this bariatric surgery place messaged me: Hey, we’re doing a campaign on bariatric surgery, do you want to join? I blocked them. There’s this constant messaging that we’re too fat, we’re too skinny, we’re too Black. We’re not worthy as we are. I’ve had enough experiences in all areas of my life that have taught me that those are just words from people who are dealing with their own limited experiences with people, and I just have to keep soldiering on because I don’t have any choice.

I.A.: How has this shown up on the trail?

M.V.: I was at Hunger Mountain not that long ago. I know the route because I’ve done it many times. There were these people, white, they’re always white, who were trying to get around me. There’s a trail that branches off and goes nowhere. They pushed past me and got on that trail. And they just had this all-knowing attitude, like they knew exactly where they were going. I’m slow, and they eventually caught back up with me and said, “That trail goes nowhere.” I was like, “I was wondering where you were going.” So, there are just those little moments.

But then there are also those moments when people realize I know what I’m doing. I have the right gear on. They will ask me for help. I love those moments when I can be the sage, the person who knows stuff. I don’t get that a lot. But when I do it’s really cool.

I.A.: But what you experienced that day on Hunger Mountain reveals who many people expect to see on a trail. What are the consequences of that?

M.V.: We only have just a few images of who is expected to participate in those very specific outdoor activities that are a part of this American outdoor image. That erases other outdoor experiences that aren’t a part of climbing Mount Everest or Denali, or kayaking Class V rapids—those sorts of expeditions.

I.A.: You mean the “conquering” aspect of nature.

M.V.: Right. And who are the risk takers? They’re usually white males. When National Geographic named me one of its 2018 Adventurers of the Year, I was like, me? I don’t climb those big mountains. I haven’t done anything in Nepal. I’m not Sir Hillary. That’s how this culture has been built.

My outdoors was the streets of Brooklyn. In the summers we were kicked out of the apartment in the morning and told, “Don’t come back until dinner.” We were outside all day, entertaining ourselves, gaining confidence and learning how to be social with other people. And so I had an amazing childhood. In Brooklyn. In an urban area. It was an outdoor childhood. But nobody in mainstream culture sees it as such. I’d like to change that narrative.

I.A.: You recently posted on Instagram about a message that another hiker sent you about how she had issues with your geotagging the places you hiked in Vermont. What about that struck a nerve?

M.V.: It was this typical I love what you do. I’ve followed you for a number of years. I’m so glad you’re in Vermont. But. Can you stop geotagging your hikes, because these are our local trails? You have thousands of followers and you’re opening up the trails to all these new people. I immediately thought, Gatekeeping. That’s what this is. You don’t want other people on these trails.

Before I responded, I did a lot of research on the effects of geotagging. I didn’t want to come from an angry place. I know what the intention is, but the intention doesn’t matter. Your impact on someone else’s experience is what matters. The effect her words had on me was very, very negative and very sort of silencing. I want to be the person that people see and say, If Mirna can get herself to a trail, I can do that too. Or, Maybe I can ask her for help.

I don’t see any Black people on the trail here. That’s normal. I’m used to it. But this person was concerned that I was bringing more people to her trail. Which was the Long Trail.

I.A.: It’s pretty well known.

M.V.: I even said that. And so the question in my head: What is she really saying?

I.A.: I once wrote a story for Yankee about beach privatization in New England. One beachfront owner in Maine thought it was important to keep these spaces available to the public because the only way they could be protected is if more people felt a personal connection to them. You seem to be saying the same thing.

M.V.: I love seeing when trails are crowded. It means people are craving these experiences. I remember maybe a month into Covid I was seeing people on the trails throughout the week, and it was magical. When people have these experiences, they have to depend on themselves, and they come back with a newfound appreciation for that experience and for that land.

I.A.: Have you heard from people who are inspired by what you’re doing?

M.V.: All the time. I got a message yesterday from a woman who saw me on Access Hollywood, another Black woman who lives in southern Vermont. She said, I hope I don’t sound like a psycho but I’d really love to go hiking with you because I never see anybody and it’s never felt real to me that there are other Black people who do this. I wrote back, I know this feeling. Period. I concur.

Then I’ll hear things like, I didn’t think anyone with my body type can run. And then I see you’re like running up mountains. Well, at least I can try to run down the block. Or other people are like, You’re so graceful when you’re running on those trails. I never saw myself, a Black person or a fat person, running like that. I want to do that.

I.A.: What’s next for you?

M.V.: Well, I think my time is limited for sponsorships. I think the “Mirna moment” is going to be over at some point, and I have to be prepared for it.

I.A.: Does that scare you?

M.V.: I think it would have scared me two years ago. But I know I’ve been given a gift and I’m trying to use it to the best of my ability—not just for myself and my family, but I’m trying to build wealth. Because we have no intergenerational wealth in my family. None whatsoever. Nobody owns anything, and so I want to buy property here in Vermont and build a retreat compound that focuses on Black joy and Black mental health and wellness. I want to build a property outdoors that focuses on that. I don’t know how I’m going to do it, but that’s my one long-term plan right now.

Part of me also wants to write a Black parenting book using my outdoor adventures as metaphors. I feel like Black people need something else in the parenting literature. We don’t have anything that doesn’t come from trauma. So I want to write something uplifting.

I.A.: Why is it important that you build your retreat in Vermont?

M.V.: I love this place. I do. This is where I need to be. And I’ve never felt that way about a place. My son is so happy here. And my mom and my sister love it up here. I’m heavily invested in this idea of creating a space, in a place where I’ve made my home, for people like me who are trail runners.

To learn more about Mirna Valerio, go to themirnavator.com.