Vincent and His Lady

The author has never forgotten a mysterious woman she never met. Vincent was rumpled, his fine gray hair—long, yet thinning—always windblown. He wore a scarf, even in the summertime, as if he were afraid he might catch a cold in his throat. His clothes looked lived-in. You expected that he might smell. But he didn’t. […]

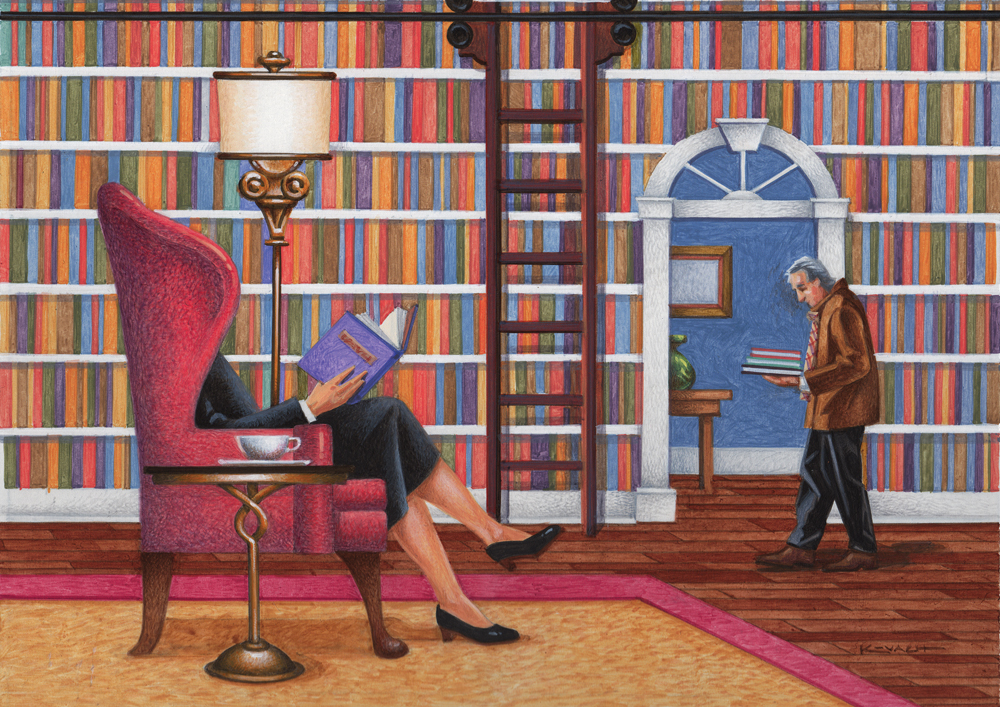

“In my mind, Vincent’s

lady was middle-aged, mysterious by nature, wealthy by accident, and withdrawn by choice. She lived in a 37-room mansion, overflowing with books.”

The author has never forgotten a mysterious woman she never met.

Photo Credit : Joe Kovach

Vincent was rumpled, his fine gray hair—long, yet thinning—always windblown. He wore a scarf, even in the summertime, as if he were afraid he might catch a cold in his throat. His clothes looked lived-in. You expected that he might smell. But he didn’t. Well—sometimes his hands smelled like fish, but not because he was unclean. Vincent’s lingering scent was the result of his routine.

Every morning, he visited the cannery down by the docks. Collecting scraps, he would fill up the two plastic tubs he kept in the grocery cart he’d snagged from the A&P. He’d push his load up the hill, and then head toward First Beach. That’s where he fed the seagulls. If you were up early, and drove by at just the right moment, you’d see the action: fish heads sailing through the air; gulls circling; Vincent, smiling.

After he’d fed the birds, he’d head back to the Avenue—Bellevue Avenue, in Newport, Rhode Island. He had errands to do: groceries, books. Most Monday mornings, Vincent would be waiting for us to open the shop. He’d have a list, and we’d get to work.

Vincent was mine. I was new, and no one else wanted him. My colleagues grew impatient, waiting while he formed words—sometimes stuttering, but mostly just slowly. He was nervous, always, and you got the impression that he worried about saying the words right, or saying the right words—take your pick. He introduced and reintroduced himself with his full name for months after our first meeting.

It was the early 1980s, and if you wanted to buy a book, you stopped by your local bookstore. If they didn’t stock the title, they’d offer to order it for you. Vincent placed a lot of orders. He’d press down hard with the bookstore-supplied ballpoint, making sure his data was readable in NCR-paper triplicate. He printed his name in big block letters, all uppercase. His penmanship was a little shaky, but his information, clear. Vincent left blank the space for a contact number. This was because he was visiting on behalf of someone else, someone who didn’t want her phone number floating around on the white, yellow, and pink copies of a Waldenbooks special-order form. Someone who valued privacy above all.

Vincent visited the bookstore every Monday on behalf of a recluse. His recluse. We gathered—from his movements (always on foot with his grocery cart) and her huge investments in our inventory—that she lived down the Avenue, which is to say: She was wealthy. Picture ornate scrollwork on tall, wrought-iron gates; two-story carriage houses guarding long, winding driveways; stands of trees between home and avenue; backyards edged by steep cliffs, the Atlantic Ocean just below. Picture The Great Gatsby, and then locate the one eccentric lady who doesn’t join the garden party.

She’s inside, upstairs, reading. Or at least that’s where I placed her. I imagined her library with three walls of floor-to-ceiling bookshelves—walnut or old oak—accessorized by rolling ladders, and one wall—with a southern exposure—banked with mullioned windows. In the winter, she read in the crisp white light. In the summer, she drew the blinds before the heat of the day hit the glass. Just down the hall? Her boudoir: flocked wallpaper, elaborate hand-carved crown molding, high ceilings. And piles of books by her bedside. Ordering so many titles, she must have read all day and half the night.

Did she have help—dusting her bedside table, straightening her stacks, removing mugs of tea grown cold while she was captivated by a twisty plot? Likely, but I never knew for sure. I only knew that Vincent was her emissary, her messenger, her go-between, and her go-get-anything guy. He was her face, but not her name, in the world.

I called her Vincent’s lady, but perhaps it would have been more accurate to refer to him as her man Vincent.

In another time, another town, we might have presumed less. But this was Newport, and we knew some of those ladies. They visited us after luncheons, dressed in Chanel and wanting to be led—or followed—around the store, picking up hardcover after hardcover. Sometimes I suggested titles, but always, I carried for them, like an after-school suitor, loaded up with his girl’s homework. When they placed a sleek credit card on the counter with a name like Drexel or Firestone, we’d ink in a tidy sum of five hundred dollars or more on the onionskin charge slip. A visit from one of the ladies on the Avenue could make our week.

We hoped—or I did—that Vincent’s lady wasn’t the wealthy “black widow” rumored to have run over two of her husbands at one end or the other of her winding drive. And when I heard that Sunny von Bülow was in a coma—murder or suicide or weight-loss plan gone wrong—I was relieved to see Vincent, list in hand, the following Monday. We weren’t sure who she was, but I hoped his lady was balanced, kind; I took heart knowing that she was an eager, wide-ranging reader.

Whenever there was a question about what, precisely, Vincent’s lady wanted (Did she prefer the hardcover or the paperback? Was she willing to wait ten weeks for one of her more obscure requests?), I handed the phone across the counter to Vincent. As slowly as he spoke, as slowly and painstakingly as he filled out his name on the special-order form, Vincent would press the buttons, summoning his recluse. She always answered. Vincent, on the phone, grew visibly more nervous, speaking only in hesitant affirmatives: Okay, yes, oh, okay, okay, oh, yes, okay.

One day, he put his hand over the receiver. “She wants to speak to you,” he said.

Startled, I took the phone, identified myself by name, asked how I might help. I don’t recall the substance of the conversation, but I remember her voice: refined but not patient, demanding but not mean-spirited. I hung up, astonished and oddly honored. In the history of Vincent and the bookstore, no one had ever spoken to the reclusive reader.

This scenario repeated itself once, then twice, and soon enough, I spoke to Vincent’s lady on a regular basis—whenever there was a question about a book on that week’s list. Her taste was eclectic; she read more nonfiction than fiction, and I dared not recommend any titles to her. But when I figured out that the Monday lists were the direct result of her careful reading of the Sunday New York Times Book Review, I became bolder: referring to reviews, asking her opinions.

The high point in my relationship with Vincent and his lady came one afternoon when the bookstore’s manager buzzed me from the back room: “There’s someone on the phone asking to speak to Miss Kate. I’m guessing that would be you?”

In time, I would leave the bookstore, passing Vincent and his lady to my replacement, who promised that he would take good care of them. I would never meet the recluse, never have tea in her library, never learn her age or her name or even her phone number. In my mind, Vincent’s lady was middle-aged, mysterious by nature, wealthy by accident, and withdrawn by choice. She lived in a 37-room mansion, overflowing with books.

In my mind, she and Vincent dined together in the evenings. Dressed for dinner, two solitary souls in an enormous formal dining room. Their crystal goblets ringing out with their silent toast. They didn’t speak, but it was never awkward. She was thinking about the book she’d just finished, and about the one she would soon begin. And Vincent: He was remembering his early morning with the gulls, and looking forward to a new dawn.