Vanishing Beauty | Vermont Photographer Jim Westphalen

In focusing on things that have been buffeted by time and tide, Vermont photographer Jim Westphalen asks viewers to see what is around them with new eyes.

“The Fishing Shacks.” Located at Fisherman’s Point in South Portland, Maine, these three lonely shacks are all that remain of the original wharf that was constructed by Scottish and Irish settlers who arrived here in 1718. With interior timbers dating back more than 200 years, these shacks predate the city itself. Local volunteers have taken on the continuous process of maintaining the historically significant buildings, which were repaired and repainted in 2023.

Photo Credit : Jim WestphalenUpon entering the photography studio of Jim Westphalen, which sits down a country lane just off busy Route 7 in Shelburne, Vermont, I stopped. A photo titled Ocean Outcrop 2 held me like few images I have seen. And I have seen many. This image from Reid State Park in Georgetown, Maine, occupied much of the wall, and I felt as if I were standing right there, on the sea-slick rocks. That is not an unusual response to a Westphalen photo. There is no glass on the frame. Nothing between the eye and the image. “I want people to sink into the picture,” he says.

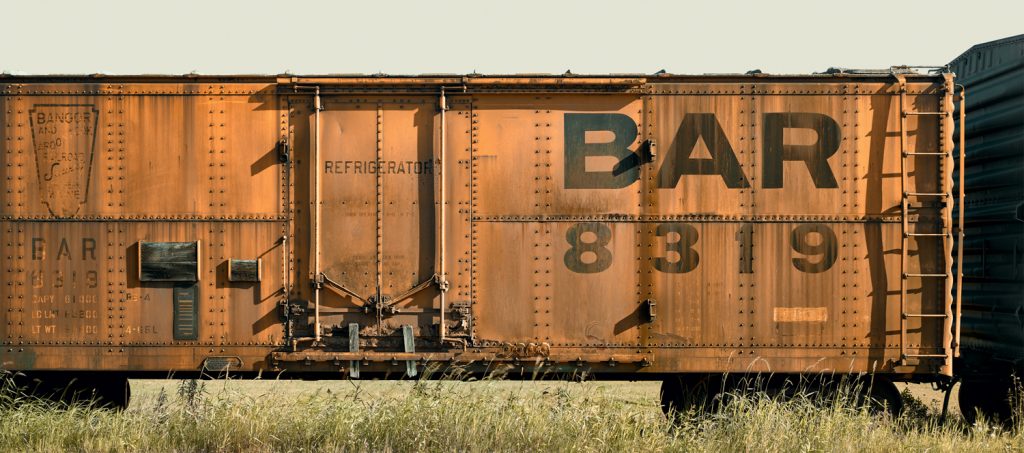

I visited Westphalen just a few months after he put the finishing touches on his first documentary film, Vanish: Disappearing Icons of a Rural America. Four years in the making, it follows his passion to create art from the forgotten and mostly unseen structures that once filled the lives of people in a different era: farmhouses, barns, churches, silos, schoolhouses, railroad cars. They are relics he has cherished for decades, searching them out wherever he is—on the coast, in rural New England, out in Western prairies. In the film, we see him peering through the large-format view camera he has carried for 35 years, hands numb from cold and snow; stepping cautiously inside abandoned buildings; being buffeted by windstorms. He will wait for hours until light and shadow converge at just the right moment. He wants to stop time. To let others see what he does: that decay is both poignant and beautiful.

Photo Credit : Jim Westphalen

Photo Credit : Jim Westphalen

Photo Credit : Jim Westphalen

After years as a successful commercial photographer, first in New York and then in Vermont, where he’s lived since the mid-1990s, Westphalen today is a fixture in prominent fine art galleries. Collectors find his work there; others see it on Instagram or in his book, or hear about it via word of mouth, and then seek out his light-filled studio, where they may spend several hours. It is new territory for him. And a prominence he did not chase.

He traces his life today to something he saw in 1996 near Poultney, Vermont. “I had just moved to Vermont, and I saw this old house that was being slowly covered by vines of wild cucumber. I remember being so excited, seeing the textures of the old barnboard, the glass-less windows, the drop shadows, the rusted roof. The feeling it was all being reclaimed by nature. I was like, Oh wow.”

Whenever he could steal time from his work shooting for resorts and magazines and architecture firms, he’d roam Vermont, stopping whenever he found a structure that seemed it was just holding on, fighting for another year, even if nobody else cared. “Over time, as I processed these images,” he says, “I saw I have a body of work. Some people told me it was too sad, that nobody would get it. But I kept shooting.”

Photo Credit : Jim Westphalen

Photo Credit : Jim Westphalen

Photo Credit : Jim Westphalen

In the fall of 2014, an exhibit in Burlington of what he called his “Vanish” work showed Westphalen he had tapped into something, a longing to know what was being lost. “I was nervous,” he says. “Will anybody care about these? [But] I saw from their reaction it was not just me. I realized I can make art. I can sell art from these images.”

A coffee table book called Vanish followed, and now the film. “My stuff is not nostalgia,” he says. “I see it as a respite from the craziness of the world. When I go out there, my cameras set up, whether on the coast or in a rural landscape, I get in that space. Just this calming thing.”

He is soon to be 65. “My wife reminds me the clock is ticking. But I feel I am just getting started. I’ll always have a passion for the disappearing.”

“Always?” I ask.

“Forever,” he replies.

Photo Credit : Jim Westphalen

Photo Credit : Jim Westphalen

To see a wider portfolio of Jim Westphalen’s work and to find out how to watch Vanish, go to jimwestphalenfineart.com.

Mel Allen

Mel Allen is the fifth editor of Yankee Magazine since its beginning in 1935. His first byline in Yankee appeared in 1977 and he joined the staff in 1979 as a senior editor. Eventually he became executive editor and in the summer of 2006 became editor. During his career he has edited and written for every section of the magazine, including home, food, and travel, while his pursuit of long form story telling has always been vital to his mission as well. He has raced a sled dog team, crawled into the dens of black bears, fished with the legendary Ted Williams, profiled astronaut Alan Shephard, and stood beneath a battleship before it was launched. He also once helped author Stephen King round up his pigs for market, but that story is for another day. Mel taught fourth grade in Maine for three years and believes that his education as a writer began when he had to hold the attention of 29 children through months of Maine winters. He learned you had to grab their attention and hold it. After 12 years teaching magazine writing at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst, he now teaches in the MFA creative nonfiction program at Bay Path University in Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Like all editors, his greatest joy is finding new talent and bringing their work to light.

More by Mel Allen