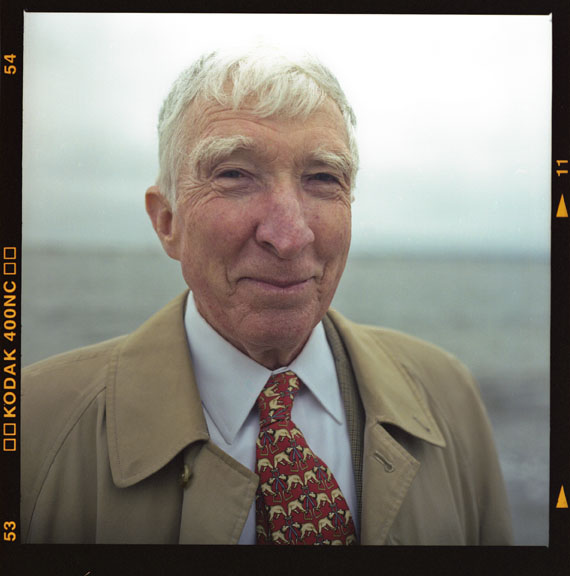

John Updike’s ‘The Wallet’

NOTE: In memory of Pulitzer-Prize winning author and New Englander John Updike, we share this short story from Yankee Magazine September 1985. Fulham, with a history of hypertension, had taken early retirement from his brokerage firm and managed his own investments and those of a favored few old clients in an upstairs room of his […]

John Updike, photograph by Jared Charney

Photo Credit : Charney, JaredNOTE: In memory of Pulitzer-Prize winning author and New Englander John Updike, we share this short story from Yankee Magazine September 1985.

Fulham, with a history of hypertension, had taken early retirement from his brokerage firm and managed his own investments and those of a favored few old clients in an upstairs room of his large white house in Wellesley.

He went to this room, overlooking his side yard’s trimmed shrubs, every morning with his Wall Street Journal and second cup of decaffeinated coffee. He kept up his charts and his correspondence, made his phone calls and a daily visit to the post office; but the illusion of integration with the larger circuits of the world was harder to maintain than when he enjoyed a corner office on the twentieth floor of a Boston skyscraper with swift-moving, enameled secretaries to shield and buttress him and to turn his hesitant murmurs of dictation into official communications on stiff company stationery. His mail, now that the postmen of an increasingly lazy and insolent government were no longer permitted to walk up to a doorway more than a specified distance from the sidewalk, came to him in a tin box down by his white picket fence, and this casual and hazardous housing somehow made additional light of the old pomp of finance.

For some days he had been expecting a large check, which the sender, a Houston oil company, had not chosen to send by registered mail or any of the express services now available. The check, in the low six figures, represented considerable acumen and initial investment on Fulham’s part, and he was anxious to stow it away in one of his bank accounts.

Every noon, after the mailman — a young man who with annoying musicality whistled opera arias as he strolled along — had banged shut the lid of the box, Fulham hurried down the long brick walk to discover, amid the bright sheaves of bills and fourth-class solicitations, whether or not the check had come. It had not, day after day. Standing by the mailbox, he could feel his heart thudding, annoyingly, like one of those large trucks that went by every now and then on their quiet street, shaking the house. A week went by, and then another. Phone calls to Houston produced only a series of drawling assurances that the check had been mailed and had not been cashed, and undoubtedly it would show up. One lady, who from the resonant lilt of her voice seemed to be black and, like the mailman, excessively musical, even explained to him that the company never registered checks on the theory that this called attention to them and in some cases had instigated thievery among the poorer class of postal workers.

The possibility of thievery had not in so many words occurred to Fulham; he had always thought of the postal service as an overarching entity, like the cloud pattern projected nightly on Channel 5, which, however unpredictable, in the last analysis inevitably delivers every bit of vapor and wind entrusted to it. Now the possibility had been raised that the system had holes in it, through one of which had fallen a sum of money that should be his, numbers that should already be punched into his bank’s computer and generating interest for his account. Each day that the check didn’t arrive, he computed, he was losing more money than it cost him and his wife to eat. His calls to Houston rose in pitch of insistence, and his comforters correspondingly rose in the company’s hierarchy, urging him, however, in the end, to wait a few more days before asking them — as was his privilege, of course — to stop the check and issue another.

He slept poorly, agitated by the injustice of it. There was no one to blame and no court in which to place an appeal — just an impenetrable delivery system stretched airily between New England and Texas. Awake at odd hours, he imagined footsteps softly passing on the sidewalk and hands rattling at his mailbox. The box itself, substituted by governmental decree for his infallibly retentive front door letter slot, seemed a perilous extension of himself, an indefensible outpost, subject to graffiti and casual battering. He tried to imagine in detail the processes of the mails — the belts, the sacks, the shufflings, the sorting machines that fling envelopes in all directions. He yearned to seize and shake that vast imagined system, to shake loose that stuck small fortune so blithely confided to a scrap of paper within another folded scrap. The wish to shake shook him; his pulpy, intimidated heart filled his skull, the bed, and the bedroom with its thumping.

His wife, awakened by his furious rotation beneath the covers, couldn’t grasp the problem, the indignity. Each day she was still eating, still tending her garden in the milky morning cool of these late summer days and then going over to the club for lunch and a swim or nine holes with her giggling, brown-legged female foursome. For Diane, perhaps there was no abyss. She had been a schoolteacher forty years ago, inculcating young minds with the lessons of cause and effect and of patience.

“The man said,” she reminded Fulham in the middle of the night, “that if it didn’t show up in a few more days they’d cancel it and mail another.”

“That means waiting more days. I should be getting interest on that amount.”

“But we don’t need the interest.”

“It’s not a question of need, it’s a question of right. We have a right to that money. Furthermore, every day that check is uncashed the company is drawing interest on its balance. Not only are we losing a profit, they’re gaining one, thanks to their own inefficiency.”

“I think you’re making too much of it. There’s no issue involved, it’s just one of those things. It got on the bottom of a mail sack somewhere.”

She thus managed in her soothing effort to stumble on the imagery that infuriated him: the flaw in the mindless system, the letter lost at the bottom of a sack forever. The outrage without a perpetrator, or at least a perpetrator who could be discovered, who would declare himself. A certain horrible smugness within the actual, imperfect and blundering as it was: an unanswerableness.

The perpetrator struck again, inside the home. Waking on Friday morning, Fulham discovered that his wallet was not on the top of his bureau, where he almost invariably put it upon retiring. He looked in the hip pocket of the pants he had worn the day before, and then, with increasing desperation, on the closet floor, under the bed, in the bedside table, on the bathroom sink, into the pockets of all his pants hanging in the closets, and, insanely, all the pockets of all his coats, even those which had been hanging in dry-cleaning bags since June.

For the years and decades of his urban employment, Fulham had carried a breast wallet, a small leather shield above his heart, gradually thickening with the years. In his retirement he wore coats only to go out at night, and so, in a minor rite of passage, a slight change of armor, he bought a hip wallet to go with his new working uniform of slacks and sports shirt. Strange and forgettable at first, and a little unbalancing, the wallet soon came to feel like a friendly adjunct to his person, a reminder, in its delicate pressure upon his left buttock, of his new, freer stage of life. It was, the wallet, almost too plump to sit upon, containing plastic charge cards for BayBanks, NYNE, Brooks Brothers, Hertz, Visa, Amoco, American Express, MasterCharge, The Harvard Coop, Filene’s, the Newton-Wellesley Hospital, and Massachusetts General Hospital, plus his plasticized driver’s license and paper cards signifying his membership in the Museum of Fine Arts, the Athenaeum, the Wellesley Country Club, the Tavern Club, the Harvard Club, Blue Cross-Blue Shield, and Social Security. Fulham was a sentimental and retentive man; the wallet also held, in its insert of transparent leaves, photos of his wife, daughter, and two grandchildren, and in its various leather pockets, a card showing his last draft classification (5-A), his insurance agent’s business card, six business cards of his own, a yellowed newspaper clipping recording his victory years ago in an intercollegiate tennis championship, and a little brown photograph, taken in a booth at the Topsfield Fair, of a seventeen-year-old girl with bangs whom he had once loved. There were also a number of obsolete receipts (for film left at the drugstore dry cleaning, a lawnmower to be sharpened) and perhaps sixty dollars in cash.

The cash was the least of it; it was the other things — the irreplaceable mementos, the credit cards that were infinitely tedious to replace — whose disappearance he could not endure, could not encompass. He methodically, yet with that frantic undercurrent which defeats method searched the large house, checking the bathroom floors, the creases behind sofa cushions, the drawers of his desk, the spaces above the books in the library. Fulham knew that on rare occasions, semi-consciously, he would find the wallet’s bulk bothersome and take it from his pocket to set it on a convenient surface. He went over the quiet events of the evening before as best he could fish them from his memory’s gray depths: dinner, a walk out into the garden to admire the asters and the first turning leaves, a little time spent in the library leafing through the latest issue of Barron’s, a half hour watching with Diane a rerun of an old movie, itself a remake, Red Shoes, with Fred Astaire and Cyd Charisse.The production numbers lacked grandeur on the little screen and the plot spun painfully between them. He had forgotten how high Astaire’s voice was, how slight. And Charisse, whom he had also once loved, looked stiff and uneasy under the burden of her fake Russian accent. Fulham had gone to bed ahead of his wife, undressing, as best he could remember, in his usual pattern, and reading himself into nodding with an Agatha Christie he may have read decades before; faint sensations deja vu teased the edges of his dissolving consciousness as Poirot paced off precise distances in the murder-stricken drawing room.

In the morning he recalled that there had been, between the times in the library and the television room, a call from his daughter, saying they were bringing the children over early in the morning so she and Rob could drive to New Haven for a football game and an overnight at another couple’s. Fulham went to the spot where he had answered the call, a nook of many small shelves just off the kitchen. Suddenly inspired, he deduced that here, amid the leaning cookbooks and rarely used hors d’oeuvre plates was where his wallet had to be; he saw it — fat, brown, with corners rubbed pale and the shape of a credit card denting the leather as sometimes a woman’s underpants show in shallow relief through a very tight dress — and emitted a small crow of triumph before realizing that what he took for the wallet was an old out-of-date address book that Diane had not bothered to throwaway. His hallucination rattled him and doubled the fury with which he searched the house room by room, corner by corner. The wallet had ceased to exist.

“It’s been stolen,” he told his wife at lunch.

Diane had had a lovely patrician face, and when she lifted her chin and thus pulled smooth the loose flesh beneath, it was still handsome, her abundant hair so utterly white as to seem an expensively sought-after effect. “How could it have been?”

“Easy. The house is big enough, anybody could slip in and out in a minute without our knowing. Anyway, it’s not up to me to figure out how to do it, it’s up to them. And they’ve done it. The bastards have done it, and I’m going to have to cancel every goddam credit card.”

She looked at him coolly, giving him her full attention for once, and said, “I’ve never seen you like this.”

“How am I?”

“You’re wild.”

“It was my wallet. Everything is in it. Everything. Without that wallet, I’m nothing.” His tongue had outraced his brain, but once he said it he realized this to be true: without the wallet he was a phantom, living in a house without walls, worse than a caveman open to the wind and saber-toothed tigers. “And I know why they took it,” he went on. “To get the bank card. With that bank card they can now deposit and draw on that check they stole earlier.”

“Deposit it in your own account?”

“And then transfer it to their own, some how. I don’t know, I don’t know how criminals do their work exactly; that’s their job. I do know that with these computers there’s no more common sense in banking — a wino off the street can walk away with ten thousand dollar s if he knows how to satisfy the idiotic machine. People and institutions are being — what’s the phrase these kids have? — ripped off all the time. We ourselves have just been ripped off of — “He named the amount of the lost check from Houston and her blue eyes went round as she began to believe him. “Don’t you see?” Fulham pressed. “The check, and now the wallet — it’s too much of a coincidence.”

“I can’t believe,” Diane said weakly, “it’s as simple as you make it sound, with all these safeguards — our code word, for instance.”

He scoffed: “Hundreds of people know our code word by now — all the employees at the bank and anybody who’s ever stood behind us in line.” It was irrefutably clear to him that forces out there beyond the horizon of towering beech trees and dormered slate roofs were silently, invisibly conspiring to invade him and steal all his treasure. Every door and window, even the little apertures of the mail slot and the telephone, were holes through which his possessions, the accumulations of a lifetime, were being pulled from him. Ruinously the world has cast property into the form of nebulous, mechanized fluidity. The cards in the missing wallet opened into slippery tunnels of credit, veins of his blood. Fulham stood, feeling nauseous. “I’m going to call Houston and stop the check,” he told his wife. “Then the bank and freeze my account.”

Even as he acted, Fulham knew his enemies, armed with his wallet, were running up giant bills buying cars, clothes, front-seat theatre tickets, mockingly extravagant meals. Yet the girls he talked to that Friday afternoon counseled delay; they all sounded seventeen, with placid, gum-chewing voices. As a group they seemed to have dealt with momentarily disappearing wallets before. Houston did agree to stop payment on the check, but the bank said the computer could not possibly be programmed to stop his account before early next week. The credit card offices all had busy phones and differing policies, and by the time Fulham hung up in exhaustion, his credit lay in a tangle, a hydra with a few of the heads cut off but most still writhing. He went through the whole house again, trying to imagine his self of yesterday in every tidy room, including the small room, once a sewing room, where they watched television. To discourage watching, the Fulhams had furnished it austerely; there was only the bare set, an oval rag rug, and a cushionless Windsor love seat with a plaid blanket neatly folded against one arm. The wallet’s non-existence rang out through the rooms like a pistol shot that leaves deafness in its wake; he stood stunned that an absence could be so decisive. It occurred to Fulham that the house would feel like this the day after he died.

Downstairs, the front door slammed and Diane’s after-golf shoes tapped across the floor. “Got the mail,” she called up. In his distraction he had forgotten to make his usual noon trip to the box at the end of the brick walk. But into his subconscious had filtered, hours ago, Rodolpho’s “Che gelida manina” from La Boheme, whistled off-key. The mail was dumped on the hall table with the petals fallen from the summer’s last roses. A long sand-colored envelope from Houston lay amid the junk and bills. It held the check, dated three weeks ago. No hidden message, no mark of misdirection or extra wear on the envelope betrayed where it had been for so long a time. In this blankness he felt a kind of magnificence, the same kind that declines to answer prayer. He found himself not consoled. Payment on the check had been stopped, it was worthless.

He awoke Saturday morning with a soreness in his stomach, a chafing hairball of vague anxiety that clarified into the conscious thought, I am a man without a wallet. The arrival of the check had lessened his fears of criminal conspiracy but isolated the wallet’s loss upon a higher plane, where it merged with landscapes and faces that had once belonged to his life and would never be seen again, melted into the void like the sad, sticky, oddly plausible stuff of dreams. Shame had replaced rage as his prime sensation; he had no wish to leave the house or go to his makeshift office or face the grandchildren who, downstairs in the hall, were noisily arriving. His daughter’s and his wife’s voices twined in a brief music ended by the slam of the front door and high heels briskly retreating down the walk. The children, an eleven-year-old boy and a nine-year-old girl, spent the morning gorging on television, and at lunchtime little Tad handed Fulham his wallet. He said. “Did you want this, Grandpa? It was all folded up in the blanket.”

His fat, worn wallet. His own. “Oh, dear,” Diane said, putting her hand to her cheek in a choreographic gesture that seemed to Fulham to parody dismay. “When Red Shoes ended I tidied up and must have folded your wallet in without realizing it. Remember, we put the blanket over our laps because of the draft?”

That made sense. The nights were getting cooler. Now Fulham recovered a dim memory of being annoyed, on the hard Windsor settee, by the lump in his back pocket. He must have removed it while gazing at Cyd Charisse. As if in another scene from the movie he saw himself, close up, hold the wallet in his hand, where it evaporated like a snowflake.

“Grandpa has lots of wallets,” Ted’s little sister, Dorothea , chimed in. “He doesn’t care.”

“Oh now, that’s not quite true,” Fulham told her, squeezing the beloved bent book of leather between his two palms and feeling very grandpaternal, fragile and wise and ready to die.