Magazine

Kim Block Fan Meets Idol | ‘This Just In’

For the author’s sister — an devoted fan of Kim Block, the nightly television news from Maine delivers the most riveting stories of our time and place.

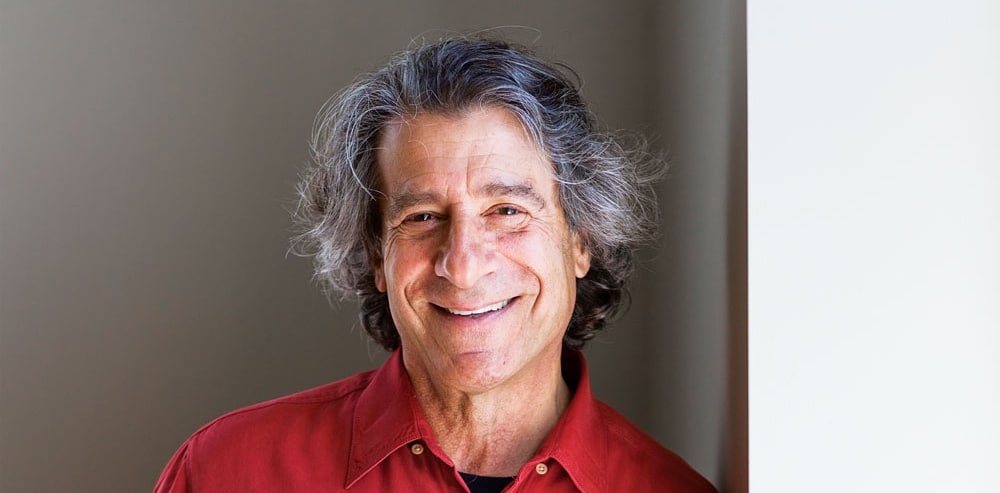

Photo Credit : Harris, Sean Alonzo

My sister Betty, who cannot consistently count past 10, is a news junkie. Every evening, in a ritual that reflects her scrupulous sense of order, she prepares her TV tray: Glass of milk. Potholder. Plate of casserole (cooked by our sister Anne) placed on potholder. Fork to left of plate. Little Debbie cake to right of plate. Only then will she settle in, one narrow thigh crossed over the other, for her nightly visit with her idol, Kim Block, longtime anchor for our local CBS News affiliate.

At 6:00 on the dot, the same incongruous vision: two intensely focused women face to face, one on screen in a silk blouse, the other in her sister’s den, wearing a child-size hoodie and size-0 sweatpants. Despite their staggering outer differences, Betty Wood and Kim Block share a few essentials: They’re close in age; they live in Maine; they love the news. Each has worked at the same place for 30 years: Kim at Channel 13, Betty at a community program for developmentally disabled adults. And, as Betty has pointed out, they each ride from time to time in a work van–Kim’s a high-tech affair emblazoned with the Channel 13 logo, Betty’s a used Dodge Caravan with seven seats and a chairlift.

When Kim brings news of blood and murder, her admirer briefly flees the room; otherwise, Betty is the ideal listener. She “reads” Kim Block the way Victorians once read novels: for guidance on how to comport herself, how to scrutinize a world beyond hers, how and when to be shocked, or captivated, or aggrieved.

“Hear this,” she’ll say to Anne, darting into the kitchen for the nightly recap. “Confetti in Portland!”

“What?”

“On the bank. They had a can!”

This is Bettyspeak; you get used to it. “Graffiti, you mean? Spray paint?”

“Spray paint!” Although my big sister is a cheerful soul, she likes umbrage as much as the next guy. Slowly, so slowly, she’ll shake her head like an exhausted schoolmarm, tsking three distinct times, the better to lament the tedious frailty of her fellow man. If reported by Kim Block, even the pettiest crime–some nameless youngster tagging a bank wall–will merit Betty’s eternal indignation.

A couple of weeks following the vandalism at the bank, she comes to visit me in Portland, patrolling the scenery from the passenger seat of my car, on the lookout for “confetti.”

We’re on Washington Avenue, on our way to a surprise. “Look at that man!” Betty huffs. “On a phone!” Kim Block has reported on this: Cell phones are bad. Worse than confetti.

“It’s okay, Bet, he’s not driving.”

Head shake; three tsks.

“Bet, he’s not even in a car.”

Unconvinced, she remains silent as we pass the maligned pedestrian and pull into the Channel 13 parking lot. “Here we are,” I tell her. “Now guess.”

She glances around: no Walmart, no Macaroni Grill, no Rite Aid, her three most requested destinations whenever she visits my graffiti-ridden, cell-phone-talking, crime-infested metropolis.

“Look over there.”

She recognizes the logo, turns to me in disbelief: “Kim Block?”

“Follow me.”

“Kim Block is the surprise?”

“I’m not saying.”

She shoots out of the car–as quickly as an arthritic, 86-pound woman can shoot–and beats me to the door, where I break the stupendous, prearranged news into the intercom: “Betty Wood is here for her tour.”

We wait in the lobby while Betty ogles framed headshots of Channel 13 celebrities, whose names Betty recites as if recalling the 12 Apostles. Then the woman herself appears, crisp and gorgeous in her studio makeup and a pearl-pink dress.

“Hiiii, honey!” Betty crows, darting over. “I watch you every night!” She offers Maine’s chief anchor the Betty Wood handshake, an exchange akin to gripping the paw of a baby mouse.

“Well, hello!” Kim says, suddenly beaming, and I count two more similarities between my sister and her mentor. One: excellent smilers. Two: in the people business.

“Did you get the van fixed, honey?” Betty asks, referring to a fender-bender involving the Channel 13 road crew that Kim reported more than 15 years ago.

“My goodness, Betty,” Kim says. “You remember everything.”

I laugh out loud; Betty remembers who got what for Christmas in 1972. She remembers the time I growled at her when I was 8 months old and she was 3. “How’s the people who lost their house?” she asks, continuing her inventory of prehistoric Channel 13 stories, until Kim–realizing this could go on for days–politely interrupts to ask Betty about her own work.

“On Wednesdays we do Wheels on Wheels,” Betty says. “For the old people to eat.” She pauses, adding, “You do a good job, honey!”

Kim slings an arm over the bony shoulders of her new friend and leads her to a guy named Matt who’s going to give the studio tour. “This is Betty Wood,” she tells him, “my biggest fan.”

After a tour not unlike the fulsome whistlestops of a presidential campaign (“Hiiii, honey, I see you on the weather!”), Betty and I settle onto a VIP couch a few feet from the anchor desk to watch Kim deliver the noon news.

Betty leans forward, legs crossed, chin on fist, exactly the way she watches the news at home. A monitor hangs well within our sightline, but I’m pretty sure my sister believes this is a special bulletin for an audience of one. Two, if you count me. Which she doesn’t.

“When that red light goes on …” Kim instructs us, putting a finger to her lips.

But Betty is no casual listener. And because today’s broadcast turns up a double doozy–propane fire in South Portland, hurricane advancing on New England–she cannot contain herself.

“OHHH!” The monitor blazes with sky-licking flames. “OHHH!” I lay a hand on her knee: Wood-girl signal for shhh. Then, a dramatic shot of a tree crash-landing on a school bus: “OHHH!” Knee again; she covers her eyes.

The weather lady takes over for a segment–more shivering trees, more gasping and eye-hiding–and then, mercifully, Kim comes back with some soporific football scores and a benign wrap-up piece about the Girl Scouts.

The instant the green light blinks on, Betty flings herself out of her seat and darts to the anchor desk, where Kim is straightening up her papers. “Hear this, Kim Block,” Betty says. “There’s a hurricane coming!”

“Oh, I know,” Kim says. “I heard all about it.”

“And the profane fire?”

“My goodness, yes! I heard about that, too!”

“Isn’t it something?”

“Well, it certainly is!”

As Betty and Kim take their leave, hugging like lifelong pals, I try to puzzle out this moment–one like so many others in which I’ve unearthed another layer of my sister’s unique and fully flowered life. “Boy oh boy!” she says as we head back to the car. “That profane fire!”

And there it is. I’d meant to thrill my sister by arranging for her to bask in the moon-bright halo of fame–but in truth, Kim Block might not even register on Betty’s A-list of celebrity, which includes certain Walmart greeters, all babies, and the guy who drives the garbage truck.

In Betty’s world, Kim Block stars on a different list entirely, a list called “Hear This”–words as old as Homer, as old as the campfire, words that summon our human hunger for story, parable, gossip, warning, news. Our preferences lean toward tales of mayhem, but in the absence of a shockeroo we’ll take a 20-pound zucchini or a sixth-grader who sold 10,000 cookies.

Every weeknight for 30 years, Kim has told Betty of elections and earthquakes, bombs and bake sales, teachers and terrorists, confetti and crime and controversy–all the stories that make us us. And Betty has faithfully received these stories of our time and place, as riveted as the first hearer of the first story related in the glow of the first embers.

To enthrall another person, you need not be famous. You need not be beautiful. You need not wear a pearl-pink dress. On Monday, after her big Kim Block weekend in the city, Betty will, in this order, get out of the van; hang her coat in a locker; stow her lunch in a cupboard; get her Pepsi out of the machine, three hours early, to store in the community fridge. Then she’ll take her place at a work table piled with clothes to sort for a secondhand shop.

“Hear this,” she’ll begin. Her listeners will lift their heads, alert for information, and turn their faces toward this trustworthy, wholehearted bringer of news, the one whose turn it is to tell the tale.

For a review of Monica Wood’s new family memoir, When We Were the Kennedys, turn to p. 24 in this issue.