The Silence of Soldiers

All the author knew was that his father had been in the Air Force during WWII. Then he found a diary.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanBy Howard Mansfield

The old men stand in young men’s uniforms. They stand at attention. There’s Ray in Navy white, Jarvis in Marine khaki, and Howard in Air Force blue. We have gathered on our small New Hampshire town common to dedicate a memorial to the veterans of three wars: World War II, Korea, and Vietnam—the last, surprisingly, 50 years gone. It is a simple monument, a large, handsome granite boulder with a smooth face for a bronze plaque of names.

The stone is unveiled. A mother who lost her son in World War II—oh, so long ago—is steadied to come forward. We applaud; it’s a meager tribute. This poor old woman seems to be knocked apart by grief, her mourning renewed.

A lone trumpet starts to play taps. I look at the old soldiers, the men I know. They are far, far away. We can’t follow them. It’s what we can’t see that matters most: the reed-thin boys they were at 19 going to war, and all those who never came home, their friends and comrades who were killed. Taps echoes, mournful, low.

We scatter. Moments later the stone stands alone.

* * * * *

When I grew up, “the war”—World War II—was everywhere—in movies and books, on TV, and yet most of it was hidden, untold. What the men up and down my street—home from the Navy, Marines, Army—what they had seen was left unsaid. What my father had done in the Air Force was never mentioned. It was like growing up on an iceberg. We were afloat on a hidden history. The real war was missing.

Once, and just once, my older brother and I were watching a war show on TV—12 O’Clock High. This was my father’s war, but in different bombers, fighting just before he got there. This should have been his story. But he wouldn’t let us watch it—and this in an era when most parents would let you watch just about anything.

Why? He wouldn’t say. But why? we persisted. All he said was that the pilots and crew on the TV show were too old.

And he was right. His pilot had just turned 22. The navigator was an old man; he was 25.

My father was a 19-year-old kid from New York City, from the Bronx. A 19-year-old with a bad left hand, malformed from a birth defect. Pincus Mansfield. He was turned down at first, 4F. But he went back—many times, we think—and convinced the Air Force that they couldn’t fly without him.

This was in 1943. The Army Air Forces, as it was then known, had boasted that they accepted only the finest, fittest men, but in 1943, in the skies over Europe, they were losing 75 percent of their men. They needed a one-handed Bronx kid who’d never been in an airplane, of course, and had fired a gun just once—a BB gun.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Howard Mansfield

He became a gunner, standing behind a machine gun at an open window of a B-24 bomber, at 20,000 feet, 25,000 feet, in poorly heated overalls and gloves. Frostbite was rampant—the Air Force’s most common injury. He got frostbite—his first Purple Heart. That frostbite would send him to doctors for the rest of his life. (“It’s nothing,” he’d say. “An inconvenience.”)

By the time he got to England in 1944, the war was going better for the Air Force. They were losing only 35 percent of their crews, on average. Each time he flew across the Channel, he had a one-third chance of not returning. On his 19th mission, he was hit by flak over Kassel, Germany, and was carried off the plane on a stretcher. He passed through a series of hospitals that sent him stateside months later.

Do I know all of this because we’d talk about it around the dinner table? Do I know this because he gave us those When-I-was-your-age speeches?

No. He never talked about the war and we learned not to ask. “I’m not gonna tell any war stories,” he’d say. In choosing silence he was like most men of his generation. It was a rule with him and millions of other men.

But the memories of that war were hiding out in our house. I knew he’d been in the Air Force—there was an old uniform under the stairs in the basement, and he did talk just a little bit about how welcoming the English were—but nothing ever about being in the air, in battle. Not a word.

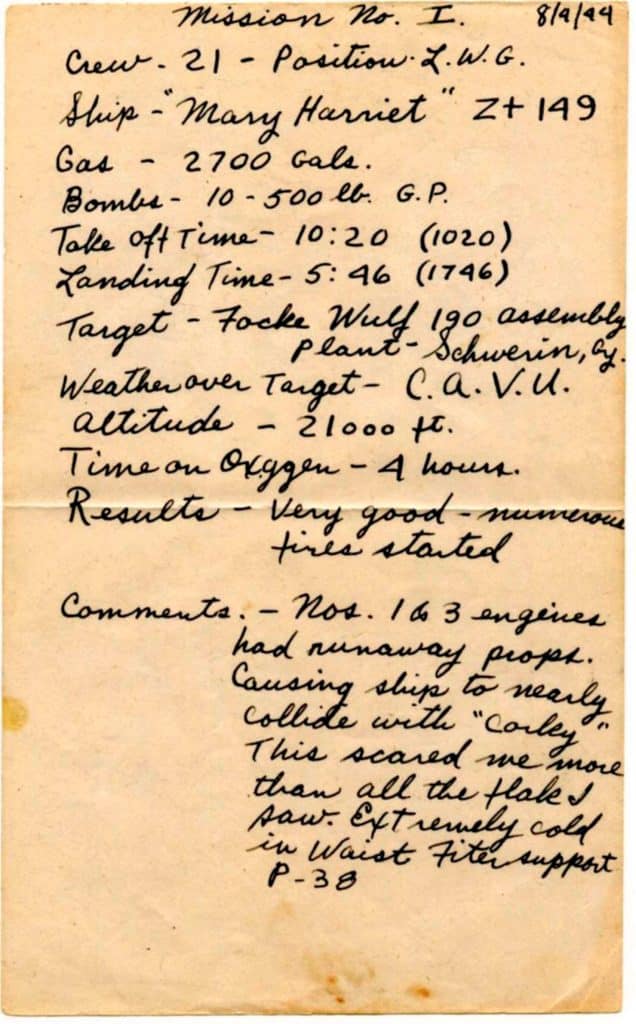

After my father died four years ago, we were cleaning out the old family home. I found a small, folded set of pages that had sat in a drawer for 65 years. It was a short journal of the bombing missions he had flown. I had no idea he’d kept this record. Airmen were forbidden to keep diaries. And when I turned the last page, there was a lengthy typed note in that stilted military lingo from the base censor. They were seizing his diary, but—once he signed the censor’s note—they’d return it to him, after the war, to 1639 Monroe Ave. in the Bronx.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Howard Mansfield

I quickly read through it, drank it down in a gulp. Some of the missions he flew were harrowing, marked by attacking fighter planes, big anti-aircraft cannon firing from the ground, blowing holes in his bomber, and wounding crewmen. They had limped back to England flying on three of the four engines with another engine threatening to quit. He’d seen bombers blown out of the sky, exploding into nothing—10 men, 18 tons of aluminum with tons more of high explosives and fuel: Just gone. And they had to fly on.

He had seen war as all the flyers saw it. He had seen flak from the anti-aircraft guns hitting the big bombers in a rain of steel pellets. It sounded like hail on a tin roof, like BBs rolling around, said the airmen. It could tear into the bomber’s aluminum skin with a “shriek” or a “hissing.” It could hit the head of your pilot or miss by an inch. Loose, hot steel rattling around, as if your anxieties had taken shape. It was lethal with a randomness that was cruel. They could smell the flak through their oxygen masks.

The stories of flak are a literature of near misses, of geometry, chance, and luck. It was a universe in which an inch or two separated life and death or injury. Minutes. Inches. Banal changes that meant living or dying. Back in the peacetime world—working nine-to-five, taking children to get shoes—how could the veterans explain that they were only in this life by a few inches? It was as though they’d realized, years before the physicists’ theories, that many universes exist side by side: the world with them and the world without them. They saw it and they had no words for it.

* * * * *

He served in the 453rd Bombardment Group of the 8th Air Force. Just before he got there, the unit was run by Ramsay Potts, age 27. Potts had been a flight leader in the daring and costly raid on the Nazi oil refineries in Ploesti, Romania, a raid in which 178 B-24s took off, and 54 never returned. More than 600 airmen were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner.

Potts came home and put the war away. Long after the war, Brigadier General Potts told a historian: “It was decades after the war before I felt like I wanted to talk about it. I think the experience was so profound and the danger so great that you’d feel when talking to people who hadn’t experienced it that maybe they’ll think I’m exaggerating, maybe they’ll think I’m bragging, maybe they’ll think I’m trying to make this out to be more than it really was. But the fact of the matter is that it was an extremely dangerous, hazardous task every damned day you went on one of these missions. You could even say that to some extent you were exposed to danger on the ground at your base because the Germans would try to launch some kind of attack on the bases in England.”

Photo Credit : Library of Congress Prints & Photographs Division

Even with the memorials, and the big movies and books, each war is private. “War happens inside a man,” said Eric Sevareid, a CBS radio correspondent who covered World War II. “It happens to one man alone. It can never be communicated. That’s the tragedy—and perhaps the blessing…. And, I am sorry to say, that is also why in a certain sense you and your sons from the war will be forever strangers.” Each war is many wars. It was a world war: It happened in thousands of places to millions of men, women, and children. The soldier, the airman, is only one guy landing on the beach, in a tank, in the air, in his tent or barracks. One guy sent here and there. One war happening millions of times.

The veterans who were welcomed home in victory would remain, just a bit, “forever strangers.” Behind their silence was an experience too intense and too personal to be expressed. For some veterans there was trauma; there was what came to be known as PTSD. And there was remorse. My father regretted having to kill, he told one of his grandsons who got him to talk, only for a few moments, about the war. It’s what had to be done, but this was a remorse he carried to his last days. When another grandson was leaving to go live in Germany, he said, “Don’t tell them what your grandfather did to their beautiful country.”

But above all, not telling was a code of honor. This was an unspoken code about what is said and what is not. This mattered greatly to my father and the men of his generation. The ugly things you had seen in the war, and what you felt about that, all that was left unsaid. They carried that burden. By their silence they said, I give you peace. Take it. Take it and don’t ask me for more. I will tell no war stories.

Adapted from I Will Tell No War Stories, to be published April 2024 by Lyons Press.