The Hardwick Blueprint | The Civic Standard in Hardwick, Vermont

How one Vermont town’s quirky civic experiment became a primer on community-building.

Tara Reese (left) and Rose Friedman of the Civic Standard, a homegrown community center on a mission “to make events where everyone is welcome, and everyone comes.”

Photo Credit : Anna WattsIt was a crisp October afternoon in Hardwick, a hardscrabble town of 2,900 souls in Vermont’s Northeast Kingdom, and the door to the Civic Standard was wide open. Kids on their way home from school helped themselves to free muffins. A woman with jittery hands took advantage of the Internet access to figure out how to catch a bus to the next town for her job-training program. A couple in Carhartts picked up some free tulip bulbs to plant in preparation for a spring tulip festival, a Hardwick tradition from the 1950s that the Civic was hoping to revive. Posters from the Civic’s eclectic series of events—concerts, bonfires, trivia nights, haiku workshops, karaoke—lined the walls.

The Civic Standard occupies a ramshackle red clapboard building on Main Street filled with threadbare couches, rickety tables, and random coffee mugs. Like a college dormitory lounge, it exudes the comforting vibe of a place you can’t possibly mess up any further. It was the home of TheHardwick Gazette for 133 years, until the newspaper’s new owner stopped printing during Covid and eventually handed the building to the Civic to support its “weird experiment,” as cofounder Rose Friedman puts it.

Vermont’s media, arts organizations, and community leaders all agree the Civic Standard is something new and vital, although nobody is sure what the heck it is. When I pressed her, Rose described it as an exploration of what might happen when you combine art and necessity instead of keeping them separate. “Like, if you take the soup kitchen and the theater as two extremes, what’s the place where they converge?”

Photo Credit : Anna Watts

Photo Credit : Anna Watts

That question has preoccupied Rose since her years at Bread and Puppet, the celebrated political theater troupe headquartered in nearby Glover. Rose met her husband there, and in 2007 they formed Modern Times Theater, which brought puppet shows and vaudeville skits to underserved places like Hardwick, a town that holds a heterogeneous mix of families that have been scraping by for generations and next-gen farmers and artists drawn by the region’s good soils and gorgeous landscapes.

The Modern Times shows were hilarious and popular, but over time Rose began nurturing ideas for a new kind of social theater—one that would internalize the Bread and Puppet ethos of “living the society that you would like to see flourish,” she said, and could be truly integrated into the life and imagination of a town. “I kept saying, ‘I just need a door on Main Street… I just need a door on Main Street.’”

Now she had one, and it was being put to full use. In the kitchen, a 9-year-old girl named Kaydence was making a giant pan of apple crisp for the free supper the Civic throws in the adjacent pocket park each Wednesday; on hand to offer light guidance was Civic cofounder Tara Reese. Since it was fall, Tara had set up her old cider press in the park, and locals were already stopping by to unload baskets of backyard fruit.

Nearby, Kaydence’s father, a 30-year veteran of the New England restaurant scene who was tatted up from the tips of his toes to the top of his bald head, was using his one night off to cook the main course, a surprisingly sumptuous ratatouille. “It’s kind of a karma thing,” he explained when I asked him why he’d volunteered. “I feel like I could use a little more.”

Photo Credit : Anna Watts

A teenager named Dean was pulling Halloween costumes out of a closet and filling a rack for the Civic’s upcoming costume swap. He had a curtain of black hair in front of striking blue eyes, a death-metal T-shirt, and the skittishness of somebody not accustomed to human kindness. Rose and Tara had met him the year before, when they taught a cooking class at the high school called “Recipe for Human Connection.” “He was a total jerk,” Tara confided to me. “Like, ‘Screw you, Tara!’ Every day. And I was like, I’m gonna get to you somehow.”

But he dropped out of school before she got the chance. After that, she saw him on the street almost every day, and after six months of overtures, he finally came inside and ate some food. “I think he didn’t have many options,” Tara said.

So they put him to work. He’d just been hired as the Civic’s first employee, 20 hours per week. It turned out he could make a mean snickerdoodle. And he admitted to me that he’d actually had a more favorable impression of them than he’d let on. “They were kind of annoying, because they were always telling me to do my dishes. But they’re actually awesome people. They always have a good attitude.”

Dean also let it slip that he was newly homeless. An extremely rough family situation had ruptured once and for all, and that was that. He’d spent the previous night in an old greenhouse. Rose and Tara were working their connections to find a temporary solution while keeping all the usual Civic chaos on track. The Civic Standard was about to launch its next major undertaking—a pop-up haunted house in an abandoned garage up the street—and the first meeting was taking place immediately after the community supper. Rose was working her phone to round up a crew big enough to pull it off.

Expectations were high. The Civic had just finished its first big show, “Developed to Death,” a dinner-theater murder mystery featuring Hardwick citizens playing both themselves and fictional characters. The show sold out its initial run and then added a second run that also sold out, and suddenly the Civic was having a moment.

Photo Credit : Anna Watts

“We’ve had requests from three other towns,” Rose told me. “‘Could you come and talk to us about how to do this in our town? Like, can you just give us the script?’ But it doesn’t work that way. To tell you to do what we did makes no sense at all, because what we did is so particular to Hardwick.”

And yet, that specificity may be what makes the Civic Standard such a compelling model for other towns struggling to find ways to bring their citizens together. What happens if you look internally to generate the cultural life of your town? And what happens if you make giving and reciprocating the foundation of that culture? And what happens if you lower the barrier to participation as close to zero as possible?

No one knows yet. But a lot of people are watching.

• • • •

The beacon that would become the Civic Standard emerged from the worst darkness. On a Friday evening in January 2020, Tara’s 17-year-old son, Finn, took his own life. Finn was a remarkable kid—star of the baseball team, class president, and that rare individual who could mix comfortably with people from all walks of life—and his death devastated the town.

A few days later, people from every corner of town gathered around a bonfire at the high school for a memorial service. “He didn’t want different politics, and different wealth, and different lifestyles to divide people,” Tara told the local paper. “All he wanted was for the different kinds of Hardwick to come together.”

Through all her suffering, she never lost sight of that goal. “It seemed really pressing to me to make sure that didn’t go away,” she told me.

In that bleak winter of 2020, Rose and Tara hadn’t yet bonded, even though they lived around the corner from each other and had friends in common. “It was this very small-town-Vermont thing,” Rose explained, “where we’d both been told bad things about the other one. Like, ‘Don’t be friends with that person. She’s whatever.’”

But in the wake of Finn’s death, people organized a meal train for Tara and her family, and Rose signed up. She dropped off a basket of roast chicken and potatoes from her farm, and received a heartfelt thank-you note in reply. “And I was like, Why would I ever think this woman was not somebody to be friends with? And she was doing the same thing,” Rose said. “So then we said to each other, ‘Let’s go for a walk.’ And on that first walk, we basically imagined the Civic Standard.”

Before Finn’s suicide, Tara had been dreaming of opening a bakery, a place where people could hang out. Rose had been programming events for the local grange. Both were troubled by the hardships of life in the Northeast Kingdom. “You can really feel the isolation here, the extremes of a rural place with hard winters,” Rose told me. “The population is small enough that you can tell who is seen and who is invisible.”

But then Covid hit, and there would be no more bringing people together. “I couldn’t do theater,” Rose said. “And I was freaking out about it. Like, what does it mean to be in a culture where people can’t see shows together? What is left when you take that away? I was also thinking a lot about families where food access was scarce.”

So she decided to make soup and give it away in the grange parking lot. And to make it a party, not a soup kitchen. “Eating free soup is not immediately comfortable for everybody,” she explained. “But what if you get into a practice as a community of doing this thing together?”

She leaned hard on friends, spread the word on social media, and set up her table on a frigid January day. A friend baked bread. Others helped cook, including Tara. Rose did it the next week. And the week after. And it turned out to be contagious. “People started bringing mittens and socks they’d made,” she said. “Then a dairy farm brought chocolate milk they’d bottled. Other people brought eggs. There was this table of bounty. And people were coming and filling shopping bags. And people stood around and talked until they couldn’t feel their toes anymore. It was just so satisfying.”

• • • •

One of the people who showed up to check out the free-soup experiment was Erica Heilman. For seven years, Erica had been making a quietly revolutionary podcast called Rumble Strip. Each carefully crafted episode is an unvarnished vignette of a regular Vermonter’s life. “It’s about climbing into the firsthand experience of another person,” she told me. “And you don’t have to like them, but you do have to love them.”

In that parking lot, Erica met Tara, who shared her story of Finn’s suicide and the way the town had rallied. Erica spent the next nine months interviewing Tara for an episode of Rumble Strip that aired in November 2021. At the end of “Finn and the Bell,” a tearful Tara relates the moments after Finn’s death, as she stood in the snow and felt the remnants of his spirit filling her. “It just sort of got in me somehow,” she says. “It was like infinite compassion for every single person that had ever lived, including me and including Finn for doing this. I remember saying out loud, ‘Oh!’ Like, I understood, for just a second, why we were alive. And it felt like it was for each other.”

Photo Credit : Anna Watts

The wrenching episode became a national sensation. It received a Peabody Award, the highest honor in broadcasting, and Rumble Strip was named a top podcast of the year by TheNew Yorker and TheNew York Times.

By then, Rose and Tara and Erica were fast friends, bonding over the realization that their exceedingly different journeys were somehow the same. “I don’t think that any of us knew what this was,” Erica said. “But I think all three of us had a deep curiosity about other humans, and how people find each other across boundaries.” Each, in her own way, was trying to solve the fundamental dilemma of being a loving consciousness trapped in a lonely body.

Later that winter, Rose and Tara decided to turn Tara’s family’s tradition of burning their Christmas tree on Epiphany into a community event. They put up flyers and spread the word: Come throw your tree on the bonfire! Free chili and cornbread! “It was a Civic Standard event,” Tara acknowledged. “We just didn’t know it yet.”

People came. Hundreds of people came. The high schoolers came and the homesteaders came and the theater geeks came. People arrived by Lexus and by snowmobile. Cars slip-slided in the snow and had to be pushed.

Perhaps it was a show of support for Tara. Perhaps it was desperation to do anything during Covid. Whatever it was, an entire town burned its Christmas trees together and stayed late, scraping frozen sour cream onto bowls of chili. “It was the party I always wanted to go to,” Erica said. At the end of the evening, the three women sat around the fire together, trying to figure out what had just happened, and how to make it happen again.

• • • •

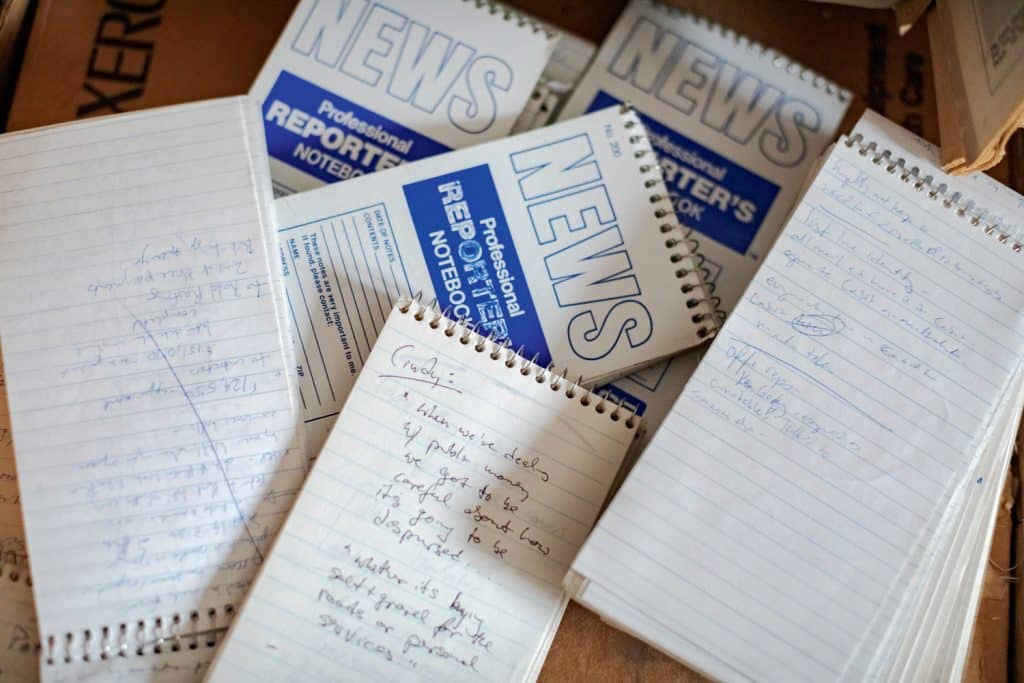

In late 2021, with the pandemic having dried up advertising revenue, the owner of TheHardwick Gazette closed the paper’s downtown office for good. Failing to find a buyer for the tumbledown building filled with broken furniture and antique printing presses, he donated it to the Civic Standard. Down came the iconic hand-painted Hardwick Gazette sign, and up went the Civic Standard sign in the same style. The newspaper-y sound of the new organization was no accident: Here was a new way for a small town to tell the story of who it was. A new way to make sense of it all.

Rose and Tara didn’t waste any time rolling out an ambitious and somewhat ad hoc slate of programming. They taught the high school class. They gave away cupcakes on the first day of school. Trivia night. Darning club. Fiddle classes and jam sessions. Dinners in the park every Wednesday. So much stuff, with so little fanfare, that the practice of doing things with neighbors and strangers began to feel less like an event and more like a habit.

Their greatest asset turned out to be the building, with 133 years of civic life baked into its patina. They kept it run-down and ideology-free. “Early on, I asked them what flags they were going to fly,” David Upson, the Hardwick town manager, told me. “And they said, ‘An OPEN flag.’”

Slowly, their plans got bigger. They reached out to the American Legion up the street to team up for a karaoke night. It was packed, and it emboldened them for the big ask: How about a full-blown murder mystery? Four shows? With dinner service?

For Rose, that kind of event had always been part of the mission. “Sometimes you need that huge cathartic release that only art can provide,” she said. “The tiny touchpoints are very important, but you also need the show that takes months to build, the amazing moment where the whole community gets to go, ‘Whoa! Look what we can do!’”

Instead of “a cheesy cardboard script off the Internet,” Rose wanted the show to be all about Hardwick. The theme became “Softwick Falls,” a proposed development. The setting: a development review meeting. The developer would be murdered, of course. And everybody in town would be a suspect, of course.

The Legion was deeply skeptical. “They had big, big doubts,” Rose said. “Because it’s a weird idea. And then it sold out in a day. At that moment, their feelings about us changed.”

People were greeted as if they were attending a real meeting. They sat at folding tables with the cast and were served spaghetti and meatballs. They had their choice of bumper stickers: “Softwick Falls: Because It Doesn’t Have to Be So Hard” or “Keep the Hard in Hardwick.” Upson played himself and was a prime suspect.

Upson told me he’d been happy to let the Civic write him into the play. He thought every town could use an organization that playfully negotiated the middle ground between people and government. “It’s bringing down walls,” he said. “I see a lot of trust-building.”

Photo Credit : Anna Watts

More than 20 locals wound up acting in the play, with dozens more working behind the scenes or serving the meal. People hung on every unlikely plot twist. It was the town catharsis Rose had been looking for.

But the feeling was short-lived. Just a few months later, in July 2023, record rains fell on Vermont, bringing with them the state’s worst flooding in a century. As houses flooded, roads disintegrated, and Hardwick’s only motel washed away, Upson raced to open an emergency shelter at the high school. One of his first calls was to the Civic Standard. “I called Tara and said, ‘Hey, I need help.’ They have their people and they’ve built up trust, so people respond.”

Within hours, the Civic went into community-meal overdrive, marshaling dozens of cooks and delivering hundreds of meals to the shelter. They organized blanket drives. They coordinated the volunteer response. They rescued a 91-year-old man from his trailer as the land underneath gave way.

When the waters receded, the Civic turned out a hundred volunteers to muck out basements, leaning hard on new friends at the Legion and their pickup-truck brigade. Hill Farmstead, the celebrated brewery 10 miles up the road, put out a new beer called the Civic Standard and donated all the proceeds to the recovery efforts.

It was stunning how fast the Civic had gone from a hazy idea to an indispensable institution. To Erica, that can be traced to the jam sessions, the plays, the meals. “As it turns out, that’s the perfect practice for effective flood relief. All that connective tissue had been forming for over a year.”

• • • •

If you want to draw a crowd in New England on a lovely fall afternoon, just set up a cider press on Main Street. In the pocket park, Kaydence and I threw the first apples into the grinder at 5:30 sharp. Within minutes, a handful of small children had gravitated to the scene and relieved me of my duties. Over the next hour, they cranked their way through a mountain of apples while adults milled around them, wolfing down ratatouille. The woman who’d been looking for the bus to her job-training program filled some to-go containers and quietly slipped away. I sat next to a man who had recently moved to the area from Cape Cod. He said he’d chosen Hardwick, in part, because of the Civic Standard. “I saw their sign and got on their mailing list. It seemed like the kind of place I wanted to live.”

Photo Credit : Anna Watts

Dean replenished the water cooler one last time and then sat down and shoveled a mountain of apple crisp into his slight frame. Despite his situation, he was feeling pretty chipper. At Rose and Tara’s urging, the high school principal was putting him up until he could find something permanent. Better still, he was part of a new skateboard committee of local teens who would be meeting at the Civic to try to get a new skate park built. They had even scored a meeting with the town manager. (When I asked Upson about it, he said he’d been impressed to receive the invite from the kids through the Civic Standard’s email. “That’s democracy!” he said. “That’s giving these kids agency.”)

Best of all, Dean was about to try out for a role in the haunted house. He didn’t know anything about theater, but the Civic had comped him a ticket to the murder mystery, and it surprised him. “It was funny,” he told me as we ate. “Really funny.” Recently, out of the blue, he’d suggested to Rose that maybe he could be in a show sometime. So she mentioned the haunted house. Scare some kids. Freak out some adults. Oh yeah.

At 6:30 it was dark and the air had started to cool, but the crowd was larger than ever, so Tara stayed behind to manage the scene while a handful of us grabbed chairs and carried them up the street to the garage. There, amid the dust and old oil stains, about 20 volunteers brainstormed through the evening until they had come up with a plan that was true to Hardwick. A mysterious object that had washed up in the floods would be on display, and it would suck people into an alternative Hardwick-from-Hell. There would be a zombie potluck with disturbingly organic ingredients, a deranged selectboard, and a nightmarish open-mic night.

The meeting adjourned with everyone promising to rope in more volunteers for the set construction to come. To me, it felt daunting. They would need half the town to pull it off. But they would get it, of course. Everyone was in.