Shad | Poor Man’s Salmon

Nobody loves shad more than the citizens of Windsor, Connecticut, who hold the Shad Derby to celebrate its return the third Saturday in May with dances, parades, and an immoderate amount of eating. Yankee Classic: “In Praise of Poor Man’s Salmon,” Yankee Magazine, May 1991 The shad? They’re always here. By the time it ‘s […]

Nobody loves shad more than the citizens of Windsor, Connecticut, who hold the Shad Derby to celebrate its return the third Saturday in May with dances, parades, and an immoderate amount of eating.

Yankee Classic: “In Praise of Poor Man’s Salmon,” Yankee Magazine, May 1991

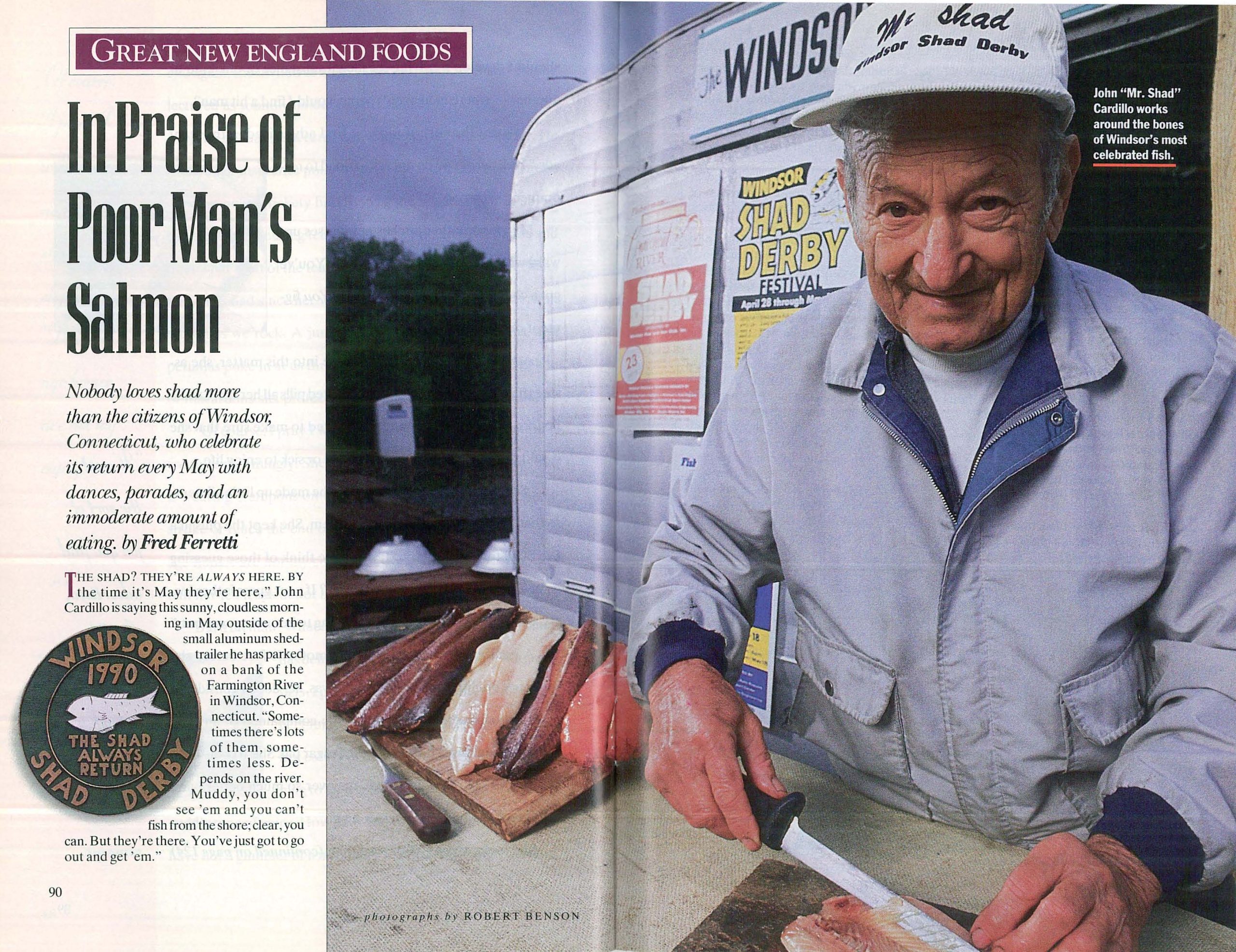

The shad? They’re always here. By the time it ‘s May they’re here,” John Cardillo is saying this sunny, cloudless morning in May outside of the small aluminum shed-trailer he has parked on a bank of the Farmington River in Windsor, Connecticut. “Sometimes there’s lots of them, sometimes less. Depends on the river. Muddy, you don’t see ’em and you can’t fish from the shore; clear, you can. But they’re there. You’ve just got to go out and get ’em.”

John, who is known throughout much of New England as “Mr. Shad,” has removed his three old, well-honed knives from the tin candy box in which he keeps them. As he slides his boning knife — worn to a thin curve — across a small whetstone and prepares to cut into the fat roe shad set on a plank in front of him, he speaks easily of the fish he knows so well, whose return up the river each spring is cause for civic celebration.

The tiny-roofed trailer, with a compact bunk and a worktable bolted to its insides, is just about the only house John has each May during the Connecticut River shad runs, and with a grand sign proclaiming it the Windsor Rod & Gun Club, it functions as well as the de facto headquarters of Windsor’s annual Shad Derby. John’s trailer is where shad caught during the derby are weighed by John on a market scale hung from the door and where he certifies such winners as last year’s eight-pound four-ounce roe shad caught by Mike Berger and Donald Gumula’s four-pound ten-ounce buck shad.

“I guess you could call me the Fish Committee,” John says with a grin.

That he is. He is also, at 83, widely recognized, as a plaque be towed upon him by his town declares, “Windsor’s Most Renowned Fisherman and Founder of Windsor’s Annual Rite of Spring, the Shad Derby.” In addition, he is a fellow who says the idea of a festival to the shad and its annual northward migration arose out of a desire first to keep clean the river that flows through his Connecticut town, second to see that “a tradition is kept, not lost.”

The Windsor Shad Derby has evolved, in its 38 years, into a six-week celebration of the shad, that fat, blue-green and silver member of the herring family.

Activities in the month leading up to Derby Day are the selection of the queen of the shad derby and her coronation ball, a shad derby gala, a shad derby road race, a senior citizens’ ball, a junior fishing contest, a shad derby Windsor Chamber of Commerce golf tournament, an art festival on the town green, and something called a Shadwreck Dance. On Derby Day there is a town-wide parade and a festival on the green with more than 100 booths selling everything from baked shad and kielbasa to braided leather belts. Broad Street, Windsor ‘s main road, is closed for the day, and this town of 27,000 plays host to 30,000 visitors, many of them former Windsor residents who make of Derby Day a day of reunion. The run of the shad is hallowed by The Windsor journal, which puts out a special Shad Derby Festival edition. “

It’s big all right,” says John, “and it’s all for a fish I call ‘poor man’s salmon.’ “

Why?

“First of all, it’s free. The Farmington’s filled with them. Second, you can catch it with a cheap 50-cent tin-spoon lure. Third, shad will fight like hell; they’re a great sports fish. And … ” He reaches to his shirt pocket and takes off the enamel pin attached to it. He hands it to me. “The Shad Always Return” it reads in gold on green. ” … like the salmon, it always comes back to spawn. Always.”

The flesh of the shad is not pink like that of salmon. It is almost beige and quite firm. The color of the meat tends to darken at the center of the shad’s body along the backbone. When cooked, the meat softens.

The millions of migrating shad eventually spawn either in waters near Holyoke, Massachusetts, or farther north in the Saint Lawrence River and Nova Scotia. They remain in northern waters until fall, when they tend to move south again to Florida. A female shad, a roe, carries within her between 200,000 and 400,000 eggs, and these she will deposit in the spawning grounds.

The roe of the shad, when it is removed from the fish, is contained in a sac that resembles a pair of fat, oversized sausages curled into the shape of an oval. The spongy mass, brownish red in color, is protected by a membrane. It is important, when removing the roe from the shad, not to puncture the sac membrane. In the several ways shad roe is cooked, broiled or lightly poached, the roe is always left in tact, for in the cooking it tends to firm up. Shad roe lovers, and they are legion, contend that the sweet nuttiness of the roe after it has been cooked is incomparable.

The shad and the roe of Georgia and the Carolinas have their partisans, but if you listen to the people of Connecticut in general, Windsor in particular, and John Cardillo most particularly, those of the Connecticut River and its tributary, the Farmington, have no equal. The prized roe is what they want when they go off to the riverbanks to fish, when they sit on bridges and small dams dangling their fishing lines, when they send their rowboats, dories, and launches onto the rivers.

On their journey up the Connecticut River the shad do not eat, so they are particularly susceptible to the reflecting metallic spoon lures that John makes as a hobby and dispenses freely to anyone who wants to go after the shad.

“The shad like the sun,” says John. When there have been heavy spring rains, with muddy runoffs into the river, the shad are more difficult to catch, but in clear running water, with the sun shining, “they just keep hitting those lures so fast you can’t pull them in fast enough,” he says.

“Where are they?” people ask John at the trailer.

“Where? Try under the old railroad bridge.” He points over his shoulder. “Where? They’re in the river. Here’s a lure. Get going. They’re not on the sidewalk.”

During the time of Windsor’s celebration of the shad, the fish and its roe become the town’s food of choice. Everybody, it seems, has his or her own way of preparing shad. Most tend to bake the shad and broil the roe. The shad itself can also be broiled or grilled, or breaded then pan-fried. There is even a slow-baking method that is said to virtually dissolve the shad’s many bones and make them edible. Perhaps the most popular method of preparing the roe is broiling or frying it accompanied with strips of bacon. It can also be sauteed or poached in butter.

Scott Verbridge, the chef and co-owner of Windsor’s big restaurant on the green, The Windsor House, and the man who supplies baked shad to the Lion’s Club booth on Derby Day, has devised other recipes. He bakes shad fillets and serves them with either of two butters, one of herbs, the other tomato and basil. He sautes the roe then dresses it with a Pommery mustard sauce. “I like shad smoked,” he says, and so he sends off many pounds of it to Nodine’s Smokehouse in Torrington, there to have it imbued with the smoke from hickory and hardwood. Verbridge has also devised a recipe for shad roe cakes.

There has even been preserved in Windsor a recipe for a classic method of preparing shad — planked and fire-roasted. It is called Shad Roasted on a Board and was discovered by a woman from Windsor in an 1875 issue of Peterson Magazine.

And how does Mr. Shad cook shad?

” First let me bone this one,” he says. John lays out the roe shad on the board and scales it. He then cuts off its head, “carefully, because the roe lies just in back of it.” He cuts into the body softly, reaches in and removes the liver and stomach, then the roe sac. He then flattens out the fish, flesh side up.

With his filleting knife he cuts along the backbone. “We call this her zipper bone,” he says, pulling the backbone out. Then with utmost deftness he removes the double set of ribs on both sides of the shad. “No other fish has that,” he says. He does this by inserting his knife behind each row in turn, then cutting inch by inch and pulling the flesh away from the bones as he cuts. Once these bones are out, the fish is reconstructed as a long mass of meat. ” It looks like one piece,” says Mr. Shad, “and it cooks that way.”