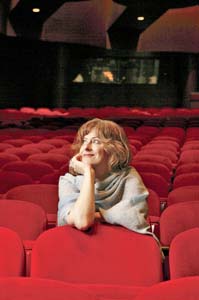

The Big Question: Opera Singer Lisa Saffer

Lisa Saffer is a 47-year-old diva. She received her master’s degree from Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music in 1984, and today makes her home in Portland, Maine. In the great opera houses and concert halls of the world, she sings in many languages, her small frame launching glorious sounds that reach to the farthest […]

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanLisa Saffer is a 47-year-old diva. She received her master’s degree from Boston’s New England Conservatory of Music in 1984, and today makes her home in Portland, Maine. In the great opera houses and concert halls of the world, she sings in many languages, her small frame launching glorious sounds that reach to the farthest balconies. Her reviews are salted with adjectives such as “radiant,” “ravishing,” “meltingly beautiful” … and high notes like “glittering sprays of jewels.”

“Singers work from inner sensation. That’s the only way you can. Your whole body is your instrument — like a basketball player’s or a dancer’s — but with the added ingredient of art. We’re distinct among musicians because the art is part of our bodies and we can’t hear ourselves accurately. We’re hearing something inside our bodies going out, so we do hear, but it’s different — like holding your ears while you talk.

“The right pitch and key feel a certain way physically in my body. Each note has its own sensation in the zone where you place it. The lower notes vibrate in my chest with a rounded quality. Middle C feels around my mouth. The higher I go, the more it feels around my eyes and in my sinuses, and it has a pointed quality. Above high C, the vibrations are so focused, hearing the note at all is difficult. You’re constantly trying to check the pitch and stay in tune by hearing the orchestra — and matching the other singers. Some singers have a person in the audience to check them, even at dress rehearsals.

“If you start thinking about doing it all in your larynx, the sound gets kind of congested. Just let your larynx do what it does and sort of work around it — a kind of indirection. Everything becomes involuntary, unlike musicians who have reeds to blow and keys to press.

“Sending the sound all the way out and filling the house is so normal to me I forget it’s amazing to other people. I keep my breathing as relaxed and open as possible and my carriage aligned, much as in bodywork or yoga. My ribs expand, so the air gently fills a vacuum. As I breathe, I drop my jaw a little, and the back of my throat feels horizontal, almost like a yawn or a smile, letting the air come into it rather than dragging the air into it. My stomach muscles support the column of air up my body. I breathe low so the air won’t tank up into the shoulders, creating tension.”

“When I release the breath into a vowel, I have the feeling that the vowel is riding on the breath, which is elastic and free and in constant motion. ‘Eee’ resonates and is amplified in the mask — all the cavities above the mouth — and has a metal feel. ‘Ooo’ has a body to it — a roundness — and I try to find the balance between the two, keeping the notes clear and warm. There’s a feeling of space in the back of my throat, in the palate, and in the sinuses. But the sound feels focused on a point a few feet in front of me, with the resonance very far forward to carry it farther. Some people call it ‘informed screaming.’

“Over and over my teacher would say, ‘Don’t think, just sing it.’ To get to a point where I could relax and allow a performance to just happen — to go forward on its own propulsion without micromanaging it — was an amazing feeling.

“After a performance my voice is very tired, but what’s most tired is my brain, because I’ve been focusing so hard, always present, aware, and reacting. It takes a lot of mental and physical energy to keep my space and my relation to the people around me alive and real — to keep my concentration and not be distracted by mistakes. Pieces of the set don’t work. Costume parts fall off. People get stuck to each other. I was on stage once where the horse pooped. Singing the role of Susanna in The Marriage of Figaro … Uncut it’s four hours long, and she sings constantly. In the third act, I get off stage and always go, ‘Why am I still singing? Why aren’t I in bed?’

“In the end, opera singing is really all about the expression. The technical apparatus is only a system to produce sounds to express something else — really the mysteries of art.”

For a list of Lisa Saffer’s appearances and an audio selection, click here.

Just now read ” The big question”. Was so informative and entertaining Lisa. Hope you are still going strong.Would have loved to see you perform, maybe l still can.