Yankee Classic Article | Does Old Age Begin at Thirty?

Not long ago one of our nation-wide questions was, “What are we going to do about the younger generation?” Today the query has been reversed; although it is implied, rather than stated openly, many older people seem to be asking. “What is the younger generation going to do about us?” This curious new attitude has […]

Not long ago one of our nation-wide questions was, “What are we going to do about the younger generation?”

Today the query has been reversed; although it is implied, rather than stated openly, many older people seem to be asking. “What is the younger generation going to do about us?”

This curious new attitude has not arisen spontaneously, however; it is the result of an astounding publicity campaign. Youth has been ballyhooed into fame with infinitely greater shrewdness and effort than any Hollywood star. Instead of one press-agent, Youth has thousands of them. Some of these aid in the propaganda from the finest of motives: honest belief that Youth, as Youth, is incomparably superior to the remainder of the human race. Others contribute their bit because of sheer fatigue; unable, themselves, to cope with their problems, they gladly turn them over to anyone who will attempt solution. But the majority of those who persistently proclaim that Youth alone possesses wisdom and courage, do so for their own, undisclosed, advantage.

There is an illuminating parallel to be drawn between the respect, verging on awe, for Youth, which has lately become manifest in intellectual, religious, commercial and political circles throughout the United States, and the relationship which develops between parents and children in the typical immigrant family coming to our shores.

Often at great self-sacrifice the parents have made possible the journey to the strange land. Once there, however, they are utterly bewildered by the unfamiliar manner and mores; ignorant of the language spoken around them, confused by external differences, they marvel at the quickness with which their children learn an approximation of the new language, and an imitation of these foreign ways. Before long, the parents are turning to the young for advice and guidance. They boast of their sons’ and daughters’ “smartness.”

In no time at all the daughters have perceived that shawls are not worn over the head, but hats are perched there; the sons quickly adapt themselves to subways, chewing gum and the current catch phrases.

No doubt the immigrant parents, concurrently with their admiration for these miracles accomplished by their young, speak often and nostalgically of the land which they have left: the land which was, and is no more, their home. Ah, that was a place where one knew what was what. Here, all is chaos. If it were not for the cleverness of the children, one would be lost, destroyed.

Thus the timid, the stupid, the easily-defeated, of the older generation – whether Boston Brahmin or tenement-dweller – continue to mourn the irretrievable past, to busy themselves in futile and unlovely laments, and to close their eyes and ears to the present. Thus, without struggle, they automatically turn over the control of that present, and with it the future, to a group which may be unscrupulous or unfit but at least possesses the sine qua non of sanity: the ability to distinguish between illusion and reality.

More dangerous than the man who believes himself Napoleon, and is consequently incarcerated, is the person who talks of the past in terms of belief in its reappearance. Youth deserves no credit for its inability to commit this crime against intelligence, yet its very lack of memories about which to be wistful seems an immeasurable advantage. It starts the race unimpeded by the heavy burden of what-used-to-be the

albatross weighing down an ominously large number of its elders.

Not all of its elders, though. While those who pride themselves upon being the most representative and the worthiest of citizens are shrieking to high heaven that it is in famous, the clock cannot be turned back, certain of their con temporaries are taking advantage of this clamor to go quietly about their own business. The success of a good deal of this business depends upon their ability to flatter and, by flattery, utilize both the unique excellencies of youth and its ignorance.

The immigrant children do not learn their way around without help; often this help is given by clever, unscrupulous elders who exaggerate the dangers of the alien surroundings and exaggerate thereby the urgent necessity for dependence upon the initiated: themselves.

Stripped of non-essentials, what is this “New World, in which only Youth call feel at home”? Isn’t it the product of verbal sleight-of-hand, abracadabra intended to dazzle? Of course, “the good old days” are gone, never to return – and never were so good as the weak sentimentalists choose to believe, anyway. But eternally, those who are unfit, as individuals, have decried change, have wished to live in any other time save that in which they are living. This is not news. What is news, is the erection by the sheer magic of words, of a phantom world, purposely made difficult, incomprehensible, with danger signs everywhere, and a powerful campaign to persuade all those over thirty years old that there is no place in it for them.

But what is the age of those who direct this propaganda?

If I were twenty, and a man old enough to be my father told me I alone had clear-sightedness, told me my generation was the hope of civilization, and my elders could not possibly possess the wisdom youth possessed, I trust I would promptly prove my clear-sightedness by inquiring as to his motives. By making certain he was not capitalizing, for purposes of his own, Youth’s eagerness for novelty, for the untried; youth’s glorious self-confidence. I would want to ascertain whether he truly believed Youth wise enough to lead the way, or secretly, in his heart, only believed Youth foolish enough to follow where it was adroitly led? By a vitally interested minority of the older generation!

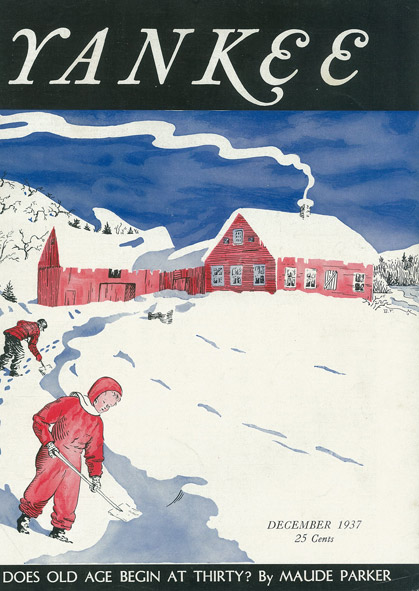

This article is from the December 1937 issue of Yankee Magazine.