When the family of artist Oliver Balf combed through a lifetime of paintings, they discovered truths about the artist’s passion, and themselves.

October 2010: I remember his being tired but relieved after a long day of international travel. The spare kibbutz “guest house” that we arrived at in advance of a family wedding amused us all: Mom and Dad bunking with their fiftysomething sons in a narrow two-room mobile home was a

Seinfeld episode come to life.

The sweetheart roses were in a simple vase on a kitchen table, and Dad must have opened his sketchbook that first day in Israel. A professional artist who exhibited widely, he was 83 and slowing, especially in recent years, but he always drew quickly and with youthful urgency. Botanical color and shape absorbed his attention like few other things. He drew the petite blooms in ink but topped them with playful pink dabs; the process wouldn’t have taken long. Almost as fast as the black, hardbound sketchbook was opened, it was closed—for good, as it turned out. It was his last painting. Five days later he was gone—suddenly and with little warning.

My mom had the idea for a last art show. She didn’t call it the last show, but it seemed implicit.

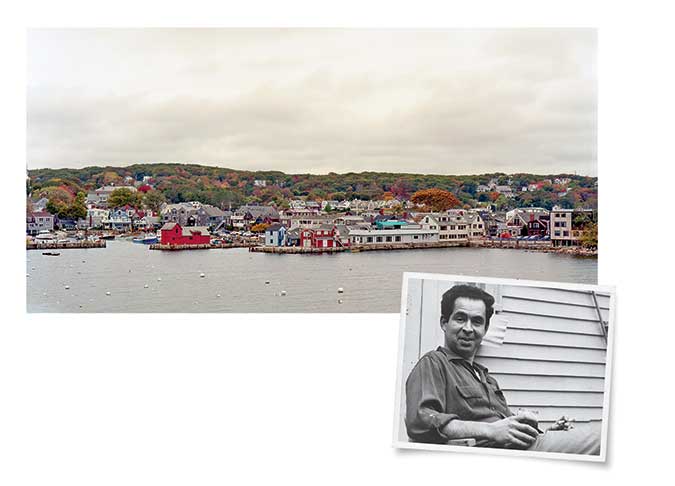

Oliver Balf, my dad, was an artist who had lived and painted on Cape Ann for more than 60 years. He’d come to Rockport, Massachusetts, on a lark—in the postwar years it was cheap and beautiful. His college roommate at Temple’s Tyler School of Art in Philadelphia figured it would cost them $37.50 to share a tent for the summer, just a stone’s throw from Old Garden Beach. That same roommate, a veteran like my dad, also discovered that they could get a monthly stipend from the GI Bill as unemployed “landscape painters.”

Dad returned the next four summers, honing his watercolor technique and selling frames on Tuna Wharf. In 1952 he was newly married and living in New York when he suggested that they move to Rockport year-round. My dad was a Hans Hofmann–trained painter; my mom, Nancy Miller, was a Dalton School graduate who called Cape Ann “the end of the Earth.” Nowadays their plans might seem like crazy talk, but they came. And most improbably of all, they stayed. Their first place was a cozy cottage apartment on Main Street, next to the now-yellow-clapboard Rockport Art Association.

The RAA was a hub of the burgeoning Cape Ann art scene and the off-and-on focus of my dad’s exhibiting life for the next half-century. It established him as a professional artist with an invitation into its prestigious ranks as a 19-year-old. It rebuffed him not many years later when his subject matter moved from characteristic seascapes to modernist still lifes. He was estranged from the RAA for a long time, but a decade ago he’d made peace. When he died on October 15, 2010, he was preparing to hold his first one-man show there in 40 years.

We went forward with the show he had planned, despite his death. It was held in a small room at the entrance to the RAA, and in our grief we found the show a helpful distraction. It was very successful—in part perhaps because of the circumstances. People wanted to pay tribute; we wanted to pay tribute. My mom went to the Art Association’s curators after the show closed and asked about the possibility of a major retrospective—bigger and more ambitious, and it would say all the things about his artistic life that this hurried, small-scale show could not. The Art Association agreed and set the date for May 2013.

Now we would have plenty of time to do all the things that needed to be done. There were thousands of paintings to review and a career narrative to explore in a way none of us had really bothered to before. It seemed particularly important for me to understand him, his art, and what moved him. I wanted to unearth everything he’d left behind, from bottom-shelf canvases to old letters. In his obituary I’d described him as a sweet man of “beautifully rebellious work,” but that sounded more authoritative than I felt. What did I know?

My two brothers and I hadn’t had much time for his art, especially during his most productive period in the ’60s and ’70s. Tom and I were popular small-town athletes. My oldest brother, Mike, was engrossed in ’60s-style activism. None of us was emotionally in tune with what he did or what he wanted. My mom worked. We were on one side, it often felt; my dad and his art on another. We’d all come closer as we became adults with young families—understanding, appreciating, moderating—but there was a period of time, when he was an artist and when art was all that mattered, that I didn’t know a thing about.

And then there was his death. Days after my niece’s wedding in Israel, a seemingly routine stomach ailment worsened rapidly. We admitted him to a hospital on the afternoon of October 14. He died hours later of congestive heart failure.

We really didn’t talk about any of it. It seemed better not to explore what we all felt: that we’d collectively come up short. The strangers around us sitting shiva in Israel had said it was good that he hadn’t suffered over weeks, months, or years, and although it was a consoling thought, I knew he wasn’t artistically ready. I had only to look in his travel sketchbook. The last work—vividly colored petals at the end of a sturdy green stalk—was unmistakable evidence of life, not death.

A year before my dad died, he wrote me a Father’s Day card. I still have it. His cards were always magnificent—whimsical drawings or cartoons that were funny and personal. Over the years many of them were plays on my passion for adventure and sport: me on top of a mountain peak; me in the jungle looking comically overmatched, wearing a Red Sox shirt (and a large, lethal snake unseen overhead). There were wry captions, like

New Yorker cartoons but only for us. This card was different. An agonized self-portrait graced the cover of simple heavy stock paper. Inside he talked about how he’d outlived everyone in his family and lots of people who were in some way part of his life: “While I’m still rational I wanted you to know how proud I am of you … I want you to know how much I love you.”

Fifteen months later he was gone, and I’d never written or said what he meant to me; I hadn’t taken the time to connect to him as a fellow artist or a grateful son. I hadn’t saved him. “He knew how much you all loved him,” my mom sweetly comforted us.

Of course this show we were putting together wasn’t a second chance for him—he was loved and respected by everyone who knew him—but it felt as though it was for us. For me.

Where do you start when you try to put together the life statement of an artist? I had this idea that we would engage leading art experts—curators, collectors, professors—a kind of esteemed panel who would guide our selection and by virtue of their eminence shower official art-world acclaim on my dad’s painting career.

For many months my mom went about the work of conceptualizing the show, collecting representative works, and framing what she said would be in the show. She knew we were busy, and each time I brought up the idea of outside experts, she looked confused and hurt. “Why do we need anyone else?” she asked.

I was treading on sensitive ground, and yet the mission to establish my dad as an unrecognized national talent seemed incompatible with the artist’s widow and children putting together favorite works. My mom’s definitiveness unnerved me. We needed someone to assess his collection and weigh in with an accredited view of what made him special, of what distinguished him. Was it his color balance? His fluid watercolor brushstroke? His oddly unrestrained, artistic risk taking?

We were not art experts. We’d merely dwelled amid his art, like the dark and gloomy bureau in the front hall at 9 Cove Hill Lane … the queer faceless lady who hovered in the living room before my giggling middle-school friends … the striking jazz figures who pleased us with their lush, hot expressions and for what they said about his passionate, music-obsessed youth.

The quiet conflict of what all of us thought was our belated duty continued through the fall and into early winter. My mom kept picking paintings and framing them—and I kept fretting and wishing for an art-luminary savior. We were now only six months out from the show. My mom and I seemed to be heading toward a battle, each of us expressing concerns about the other to the rest of the family. And there was something else: My mom felt the show’s success was contingent on people buying my dad’s work. I felt that that expectation was bound to doom the show. My dad’s work was never a big seller; it was too unpredictable, too difficult to categorize. The show should simply represent the breadth and beauty of his work, I argued—and who cared what did or didn’t sell?

My dad had only ever wanted to paint. We all knew that. In college Tom and I started a secret “Dad Fund” with the intention of sending him to Europe for a grand painting getaway. But we never came through, plundering the account for something I can’t even remember. Dad designed logos for trucks during his most creative and energetic artistic years; he created illustrations for a textbook publisher; he helped Parker Brothers’ toy designers present their ideas by drawing what they described. He’d even worked on a silly children’s book with me—something that got us on TV and page 1 of the

Boston Globe—more attention than all of his real art shows got by a mile. Some of the commercial work might’ve been fun, but it wasn’t painting. It seemed that in all of these jobs he’d sacrificed his gift for us—to provide, and to do what was expected of him.

Ultimately the crisis came in April, a month before the show, and when it did, it was over the sample invitation I’d had made. The design was contemporary and eye-catching; I was overjoyed. My mom was not, writing in an e-mail that it “doesn’t represent either Ollie or his work.” I took the criticism personally, as an accusation. She seemed to suggest that I was disrespecting the memory I was so desperately trying to honor.

We’d finally come to the crux of it: My mom was operating on what she thought her artist husband would have done. She’d been through dozens of shows and countless late-night discussions. I was operating on some sort of assumed trust: of the show he should have had.

I told my mom about a memorial service for a friend: His children had eloquently related how their dying father had told them not to worry about what he would have done for the very service they were conducting, because whatever they did would be the right thing. My mom listened, but her reaction wasn’t what I expected. She said, “No, I don’t agree.” There was a right way.

—

At the time, I was immersing myself in the collection. I was trying to load images onto a Web site, and before that I’d been putting the 1,000 or so photos of Dad’s artworks into categories: working waterfront, landscapes, seascapes, portraits, and so on.

My familiarity with my dad’s work grew, of course, but in ways I hadn’t anticipated. I’d be out in the woods on my bike or on foot and I’d have a kind of

déjà vu moment. All over Cape Ann it started happening: a ride along the muscular Back Shore; a stroll along Gloucester’s inner harbor, where rigged steel-hulled fishing boats were at anchor. My flashbacks were of the paintings I’d been browsing through days or weeks earlier. The lines of a tree’s thick trunk and the geometric formation of a pine stand in a half-lit glen brought me back to a series of paintings he’d made from visits to Ravenswood, a beautiful coastal park on the outskirts of Gloucester. Amid arched Dogtown boulders at the thickly wooded center of Cape Ann and at a sweeping overlook to Old Garden Beach the sensation struck again.

He’d traveled all over Cape Ann as a young artist. As he raised his family, he’d shifted his focus to studio work, probably because he didn’t have time to get to the wild places that had drawn him to Cape Ann in the first place. For the first time I was aware of how intimately he’d known and was attracted to the same places I was.

He’d adapted the art he made to the family and work life he was living. He hadn’t done exactly what he’d wanted to do, but he’d determinedly found a way to bring the same Cape beauty to the places where he could: still lifes in the ’70s when we were all a handful; montages of personal objects in the ’80s and ’90s. In a pile of artist’s statements and appeals to agents for representation and speeches to graduating classes at Montserrat (an art college in Beverly, Massachusetts, that he helped found in the late 1960s), I found the connective pieces I needed. “You don’t lose the experience of painting fast and catching the light—even when you are no longer physically able to do it,” he wrote. “That feeling is in you forever; it’s the hook that makes you want to keep painting.”

He had stopped crouching over a canvas on granite headlands a long time ago. I’d thought he’d given up, semi-defeated, like an old jock with bad knees who never picks up a basketball again. But a resilient emotional thread stretched across decades, from his first painting to his last. He was still “playing,” still painting fast, making mistakes, and ending up somewhere he’d never expected.

—

We made peace, my mom and I, very quickly after the dust-up. A day after her comments and my obvious hurt, she reached out, saying she liked the invitation after all. I doubt she did, but nothing for her was worth a fissure in the family. I began to see her side of it, too: how the judgments she made were because she was answering to her husband, trying to measure up as a spouse of 58 years, just as I was trying to measure up as a son. “When you’re married to an artist,” she once told her college-age granddaughter, “their first love will always be art. It was always hard.” She was simply guarding my dad’s love; every decision was filtered in a way that poignantly asked,

What would Ollie have done?

The show began to take shape as our family met weekly through April and into May. We added and subtracted from my mom’s first pass. There were private paintings she didn’t see as “show” paintings, several of them on the walls of her bedroom. “They don’t have to be for sale,” Tom suggested. “What are we talking about?”

We walked into her bedroom and saw the majestic watercolor of Eastern Point; it was clearly the show’s signature painting. On the far walls there were pictures of my mom—he’d done so many—but the colors were elegantly muted, drawn in the half-light of dawn when he was returning from a night-shift job at the

Globe. My mom and dad had argued often when I was a kid; household expenses were tight, a painting career was sliding. But this portrait of my mom struck me—it was utterly different, utterly adoring. It had to be in the show. My mom blushed.

A couple of days before the May opening, we descended on the Art Association with three cars loaded with paintings, carefully stacked amid heavy blankets. There was already a banner at the doorway and a poster in the glass-encased events box next to the walkway. I was particularly attentive to a three-foot-tall posterboard featuring a black-and-white photo of the young artist and the biographical text I’d written for the show. I didn’t want it to get dinged; it was to be mounted at the alcove entrance to the gallery. The photo looked the way I wanted him to feel: strong and at ease, relaxing in our small backyard in front of his then-working studio. You could easily imagine him back from a day of watercoloring, all the little accidents of the medium adding up to something worth quietly celebrating.

In the text I’d given his background: born in Rye, New York; raised on the Cape as a painter, where he found a community that launched not only galleries but a new idealistic art college for painters, by painters. I told how his acceptance into the Art Association had been an early success, but that the exhibit of his first painting had been a crushing disappointment—it didn’t sell—so he’d painted over it in dismay. I guess I wanted people to understand how much he cared, then and for the rest of his career, and how secretly hopeful he was that his first love—his art—would be loved in return. He’d confessed as much in an unpublished artist’s statement I’d found among his papers. He’d said that all artists want to be admired and recognized, and he was no different. With every painting not sold and every exhibit sparsely attended, he walked an emotional tightrope—stubbornly having faith that his time would come, but fearing that he wasn’t good enough and it might not.

—

“Do you want to do it or do you want me to?” asked Carol, the petite, hard-charging curator, as we paused with 50 paintings leaning against walls and seemingly acres of blank wall space in front of us. It was awkward. For weeks we’d been developing a mock show on PowerPoint slides, not sure how else to see the show. There wasn’t much in the DIY world for organizing your own art retrospective. For all my get-the-experts-in sentiment, I’d changed. I didn’t want to cede control to anyone, and Carol was good enough to let us have at it.

We were all stunned when the show was hung. It had taken so long to assemble, but it went up in a flash. Little accidents worked themselves out; pairings we hadn’t seen in the slide show organically presented themselves. Dad’s discovery of the Cape came first—the sloping headlands at dawn, the great dragging fleet on the Gloucester waterfront, the granite totems of woods-cloaked quarries—and then life at home, and in memories, and, finally, the last work, placed in a nook at the show’s end: the sweetheart roses, all five of them, not for sale.

A few nights later came the opening—and, other than Mom’s jazz-standards soundtrack not playing, it went off splendidly. Everyone seemed to come out. “It feels like he’s here,” I heard someone say. “He is,” her friend responded, gesturing across the gallery. Some assumed that the bright colors were indicative of a uniquely happy man. I knew that wasn’t exactly the case—but maybe they were the work of a hopeful man. For me, the highlight was meeting an artist friend of my dad’s who, because of a long-running feud, hadn’t set foot in the Art Association for 40 years. “I’m not all that comfortable,” he told me, “but I’m glad I came in.” My dad was a wonderful man, he said, and I knew that a man with an undimmed 40-year-old grudge wouldn’t just say that. He thought the show looked dynamite.

My mom wore a long floral-print skirt and a white blouse, accented with a corsage we’d given her. She looked relaxed—pleased at the enthusiastic reception, comforted to be surrounded by artwork that spanned their life together. She’d been unflagging in the many months leading up to the show, teaching herself to frame (and not without consequence to the fingers her flying hammer found). She’d even sat for an interview with a

Boston Globe reporter, going off the record to explain the chance, faintly illicit first meeting she’d had with my dad at a Rocky Neck jazz club—a meeting she’d downplayed, since she was seeing someone else at the time. My brothers and I loved that story, and the fact that they married a mere eight weeks after their first official date, capping it with a wild honeymoon in Chicago, where the virtually penniless newlyweds lobbed water balloons from a high hotel room in celebration. She’d given her time, her fingers, and a few of her secrets to see this through. And I think she knew that by any measure—her own, ours, my dad’s—she’d done well.

That night, and over the course of the show’s four-week duration, the response was amazing. A town lobsterman offered $2,000 for a painting of a classic fishing shack: $1,000 cash, $1,000 in lobster. My friend Brad, who tended to be a tough critic of my dad’s work, allowed how he’d seen a watercolor in the show that blew him away, that he never would have guessed my dad had done. It was the one of my mom. In a gallery walk, the guide, Ron Straka, analyzed the paintings to a large and attentive crowd, sharing how my dad had once explained his expressive work as a reaction to his immigrant upbringing, where he was often told not to say too much and to get along.

People said they’d never seen so much joy and happiness in a gallery. They seemed to react to the works for the pure feelings they presented. All the little things we might have done better in terms of presentation didn’t seem to matter or detract. Someone put a reserve on a painting I’d found only days before at the bottom of a dusty storeroom pile—just like me, smitten enough by the subject that the age spots and irregularities were ignored. Another bought a beautiful harbor scene, inexplicably signed twice. Imperfection, at least on this night, was perfection. When the show ended four weeks later, the curators told us it was one of the biggest-selling one-man shows they’d ever held.

I was pleased by the show’s commercial success and that we’d done it as a family; it wouldn’t have been the same had my acclaimed art panel put the exhibit together. When we took the show down at the end of June, we were all a little melancholy, aware that there was probably no next show. We all felt his loss in the blank empty walls. We’d fully immersed ourselves in my dad’s creative life and now we had to move on.

To an all-family lunch I brought along a beautiful letter I’d unearthed: a letter from my dad to a struggling young artist. My mom wept gently when she read it, feeling all over again his passion for being an artist—and for becoming one. It occurred to me that we’d created something not unlike a painting, and not unlike the imperfect process my dad knew and loved. “Delight in the surprises,” he’d implored in the letter. I think we finally had.

To see additional paintings and family photos, visit: YankeeMagazine.com/more