My Ancestor Was a Salem Witch

When your lineage intertwines with New England’s most infamous era, feelings about family can get tangled.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanBy Alexandra Pecci

At first, the woman seemed excited to talk to me. But that changed when I uttered a single word.

Witch.

It had barely left my lips when her expression darkened. “I wish they would take the witch part out,” she said.

We were discussing our shared ancestor, Mary Bradbury, who in 1692 was accused of witchcraft and consorting with the devil during the Salem Witch Trials. Mary was found guilty, convicted, and sentenced to the gallows, but somehow she escaped prison before meeting the hangman. The “somehow” remains an unanswered question, but the prevailing theory is that her family bribed the jailer. Apparently, greased palms were more powerful than Satan, even in 1692. However it happened, though, Mary was the only convicted “witch” who escaped.

It’s a story that fascinates me. But the woman I was talking to didn’t share my feelings.

This was early last June. We were gathered for a memorial service for Mary and her husband, Captain Thomas Bradbury, two people who had been dead for more than three centuries. Another of Mary’s descendants, Rae Bradbury-Enslin of New Hampshire, had raised money to commission two hand-carved headstones for Mary and Thomas. The headstones had been installed a few days earlier at the Salisbury Colonial Burying Ground in Salisbury, Massachusetts, where historians believe the couple are buried.

The woman and I were among several dozen people—many of us Bradbury descendants—gathered on the rainy lawn at the Salisbury Historical Society to dedicate the stones. She was chatty and friendly, asking if I was also a descendant. Yes, I told her.

“Which line?” she asked.

“Um, Judith,” I said, racking my brain for the name of Mary and Thomas’s eldest daughter, which to my relief I’d double-checked that morning. I felt like I was being quizzed about my Bradbury family bona fides.

The woman’s tone changed when I said Mary interested me because of the witch trials.

She vehemently defended Mary against the witchcraft accusations. Mary was a good Christian woman! She endured the ocean voyage from England to America! She worked hard! Raised a family! Became, along with her husband, one of Salisbury’s most respected and prominent citizens!

I listened, nodding. Of course, she was right. Mary Perkins Bradbury of Salisbury, Massachusetts, was not a witch. She was not baptized by the serpent in a river. She did not appear as a blue boar to trip up a rider on horseback. Her disembodied spirit did not torment a man on his deathbed. She did not wield her evil powers to turn butter rancid.

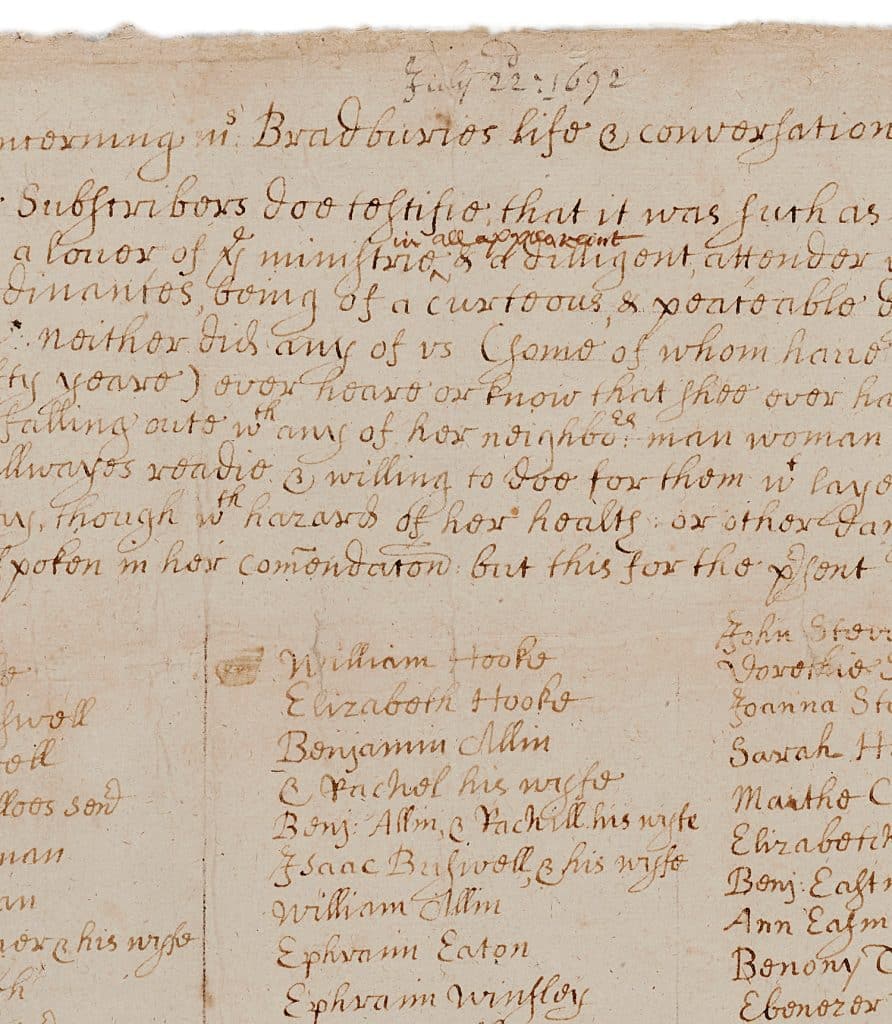

Photo Credit : Court of Oyer and Terminer, Salem Witch Trials Papers, Petition in Support of Mary Bradbury, July 22, 1692, JU-SJC/OAT/series 003, Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court Archives, Massachusetts Archives, Boston, MA

Photo Credit : Trial of George Jacobs, August 5, 1692 by Tompkins Harrison Matteson, gift of R.W. Ropes, courtesy of Peabody Essex Museum, photo by Mark Sexton and Jeffrey R. Dykes/PEM

But she was convicted of witchcraft in one of the most infamous events in New England history, one we’re still obsessed with. The Salem Witch Trials are why Mary is remembered today. It’s impossible to separate the two.

I remained quiet, and in truth I understood the woman’s distress. Despite all the time that’s passed, the wound of the witch trials remains open for many. Some resent the false accusations against their ancestors. Others dislike the Hocus Pocus commercialism of a tragedy. A few Salem attractions even spread a false history of the accused women being misunderstood folk witches or healers. “In fact, they were Christian,” historian Richard Trask told me, and would have been “completely taken aback” by the idea that anyone would say they were practicing witches.

The shame of witchcraft, it seems, is nearly impossible to shake, even across the centuries. Traces of that shame lingered within my own family, too. I’d written about the Salem Witch Trials for years before I learned I was descended from anyone involved. My mother found out while she was researching my father’s family history.

I was stunned. But apparently my father’s mother had known all along.

“Gram!” I said. “Did you know about this?”

“Yes,” she admitted.

“Why didn’t you ever tell me?”

“I didn’t like to talk about that.”

My grandmother died several years ago, but I recently asked her sister why she might have kept such a thing a secret. “Your dear grandmother,” my great-aunt wrote me on Facebook, “did not want it to be known and said it was not true.”

My grandmother certainly wasn’t alone in wanting to keep her connection to the witch hysteria quiet. Until relatively recently, the Massachusetts town of Danvers, Salem’s neighbor, wasn’t too keen on its role in the history, either.

It was in Danvers, not Salem, where the accusations of “witch” were first hurled in 1692. Danvers was known as Salem Village then, and it’s where the first two “afflicted” girls—Betty, age 9, and her cousin, Abigail, age 11—were overcome by unexplained fits and visions. They thrashed and cried in pain, writhed in their beds, and screamed about being pinched and bitten by invisible specters. Even more disturbing, it happened in the very house where God should have a mighty hold: the parsonage where Reverend Samuel Parris, Salem Village’s minister, lived. Betty was his daughter, and Abigail his niece. Frantic doctors and clergy said the source of the girls’ affliction was clear. “Who torments you?” they asked, pressing the girls to identify the witches hiding in their midst.

It didn’t take long for the girls to name their spectral abusers. They accused an enslaved woman, Tituba, and two other townspeople, Sarah Osborne and Sarah Good. But that was only the beginning. Within weeks, the hysteria spread throughout Essex County and beyond, and over the course of the next year, more than 150 people were accused, including Mary Bradbury. But that first wicked spark of witchcraft ignited in Danvers, where it became a black mark in the town’s history.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Richard Trask

Richard Trask is now the town’s archivist, but when he was a young boy growing up in Danvers, its role in the story wasn’t discussed, and for good reason. Nineteen innocent people were hanged and one man was pressed to death after the county sheriff piled stones upon his chest for days, trying to elicit a confession. Five more people died in the putrid jails, including Sarah Good’s infant daughter, Mercy, whose mother was executed.

“Back in Danvers [in the] ’50s and ’60s, in polite society, you just didn’t talk about it,” Trask told me. “It was one of those subjects that was looked upon as being not appropriate, sad. Mistakes had been made, and bad things happened to good people. It just was not a subject that most people were really talking about.”

Eventually, Trask—himself a descendent of several victims—became one of the people who helped Danvers accept and embrace its connection to the shameful history. In 1970, he led an archaeology team that rediscovered and excavated the site of the Salem Village Parsonage, where the witch hysteria began. “I always tend to think that with our excavation, witchcraft became not quite as taboo a subject in Danvers,” he said.

Today, things have changed even more. “People love to find out that they’re related to one of the witchcraft victims,” he said. I understood—I did, too. Still, I wondered whether Mary would be horrified that witchcraft is the reason her name is still on people’s lips all these years after her death, in 1700. And I wondered whether Mary would be horrified by me, too.

I have the phases of the moon tattooed on my wrist. Our home is filled with crystals, herbs, tarot cards, feathers, homemade potions, botany books, and candles. I keep pyrite on my desk for luck and black kyanite (aka “witches broom”) in my purse for protection. Instead of church, I attend full-moon circles and solstice celebrations.

I suppose I am what Mary Bradbury and her contemporaries would have considered a witch. And perhaps they would have hanged me for it.

• • • • •

The Puritan view of witchcraft was very different from our modern one. Witchcraft in 1692 had little to do with crystals and herbs and everything to do with the devil. Satan was a real presence in daily life, lurking at the rough edges of temptation, hungry to test the faithful and entice people away from God.

I saw this firsthand last March when I visited the Massachusetts Judicial Archives in Boston, home to hundreds of original handwritten documents from the Salem Witch Trials, including accusations, pleas, depositions, indictments, and even a death warrant for Bridget Bishop, the first person executed during the trials.

“Back then, they had a strong preference for written testimony,” explained judicial archivist Christopher Carter. “Thankfully, that means we have a lot of the depositions or witness testimony in written form.”

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Alexandra Pecci

Carter led me through a warehouse filled with shelves upon shelves of historical documents. It was loud inside, thanks to powerful air conditioning units keeping the space between 65 and 68 degrees and at 40 percent relative humidity to preserve the centuries-old paper and leather. Carter had pulled every court document related to Mary Bradbury. In them, her accusers make fantastical accusations against her, and Mary herself pleads her innocence. There’s even a petition from dozens of her Salisbury neighbors attesting to her “courteous and peaceable disposition and carriage.”

But there was one document that I wouldn’t be able to shake from my mind, even months after my visit. It was the testimony of Mercy Lewis, who had confessed to witchcraft perhaps in the hope of saving herself from hanging. In it, she named others who were also in league with the devil.

“Mrs. Bradbury, Goody Howe, and Goody Nurse baptized by the serpent at Newbury Falls, and that he dipped their heads in the water, and there saw they were his and had power over them,” Carter read out loud, tracing the words with his finger as he parsed the archaic handwriting, and I shivered in the chilled room.

I stared at the piece of paper, trying to grasp the historical enormity of it. It was in remarkably good shape, with only a few ragged tears along the sides. The penmanship was crisp and clear, dark upon the page in brown ink. I touched it with a single finger, this physical link between me and Mary.

• • • • •

A few months later, once the biting cold of winter had passed, I drove to Newbury Falls and stood on a bridge at the crook of a winding road, staring into the rushing water. Newbury Falls is on the Parker River in Byfield, Massachusetts. It’s a spot that had been used for industry—as a sawmill, gristmill, snuff and chocolate mill, textile mill—since at least 1636. A dead fish, an alewife, maybe, was wedged between the rocks at the river’s edge, and I thought I could smell it, rotten on the air.

Mary was a devout Christian, a beloved neighbor, mother, and grandmother who was in her late 70s when she faced the gallows. She wasn’t baptized by Satan in these waters. It was a lie so terrible that her children were eventually awarded financial reparations. Yet, I tried to imagine what people believed Mercy had witnessed. I erased the houses, the paved roads, the power lines, and even the sun. There was only the light of the moon, the menacing dark wilderness, the churning river, and Satan himself, rising up from the water in the form of a black serpent. I stood on that bridge for a long time, unsure, exactly, what I was looking for. Whatever it was, I didn’t find it.

Several weeks later, I closed my eyes during a full-moon circle led by Žhana Levitsky, founder of a coaching and teaching enterprise called Folk Magic and a self-professed traditional witch. It was a beautiful ceremony, calming and introspective. But when Levitsky implored us to “call on our ancestors,” my thoughts went straight to Mary, and I quickly backed away, as though I couldn’t shake that deeply imprinted family shame of witchcraft.

I called Levitsky later to ask: What if my ancestor doesn’t want to be called upon?

Levitsky refers to herself as “an animist and educator.” An animist believes that everything—objects, places, living things—possess a spiritual essence. That’s fitting for Salem, which still bears the deep psychic wounds of its past, even as it’s become both tourist attraction and year-round Halloween party.

Photo Credit : Frances F. Denny

“When a place of great injustice and violence is so clearly marked upon the map,” Levitsky said, “it’s inevitable that people want to come and heal that wound, that witches want to come and heal that wound.” Where Salem could have been “a hokey tourist destination that celebrates gore and violence with kitsch,” she said, instead it’s a “safe haven to ensure that the sins of history are not repeated again and again.”

She’s right. The Salem Witch Trials are the reason Salem has intentionally welcomed marginalized people of all kinds, from the LGBTQ+ community to refugees, and to witches themselves. In calling our ancestors, Levitsky said, we’re asking those “who lived and died in good ways to show us how we can become good ancestors in our turn.”

Despite—or, more accurately, because of—its history and pain, Salem itself has become a good ancestor. I thought about Mary’s new headstone, upon which Rae Bradbury-Enslin inscribed the words “wholly innocent.” Those words were Mary’s own, written in her plea against the witchcraft charges. They’re also inscribed on the ground at the Salem Witch Trials Memorial.

I texted Rae to ask her why she had chosen those particular words.

“I tried very hard not to make these stones about the trials. That wasn’t their point,” she replied. “But the fact of the matter is that it was a huge part of how Mary’s descendants remember her. I thought it was appropriate to use that for her quote, because it was also the overarching truth about her.”

Mary, by all accounts, lived and died in good ways. And for that reason, we cannot remove “the witch part” from her legacy. It was terrible, yes. But it also revealed her character—her neighborliness, her steadfast beliefs—and lodged it in our memories forever. For that, as her great-granddaughter many times over, I’m grateful. And perhaps, if I’m lucky, I can live and die in good ways, too.

My ancestor, William Phelps, who mmigrated on 30 May 1630, was a Puritan Englishman and was one of the founders of both Dorchester, Massachusetts and Windsor, Connecticut, foreman of the first grand jury in New England, served most of his life in early colonial government, and played a key role in establishing the first democratic town government in the American colonies. I understand he was also took part in witch courts and had comdenmed people witches and put to death. Do you have any information to verify this? Thanks for your help if he was or not. Shirley Keyes

This is a thoughtful and well-written essay. Thanks! It has just occurred to me that one of the most famous women in history, and certainly the Western world’s most celebrated heroine, was burned for being a “witch in league with Satan” — Joan of Arc. Her demise resulted from the coinciding of the political goals of the powerful with the unusual nature of how she discerned what was her right course of action, that is, what needed to be done. She heard the voices of saints instructing her what to do.

I was chatting with my sister and she told me about this article. We are also descendants of Mary Bradbury. Thank you for writing this article. I really enjoyed it. I’m amazed that there are relatives that live near us, however distant.

Wow that’s crazy, we’re also related to Mary Bradbury! We’re on the maiden Perkins side. My mom was a Perkins. So fun to find more people we’re related to, however distant, through the bond of familial witchcraft! I love talking about the Perkins witch.