Magazine

Mount Washington Avalanche | Nightmare on Mount Washington

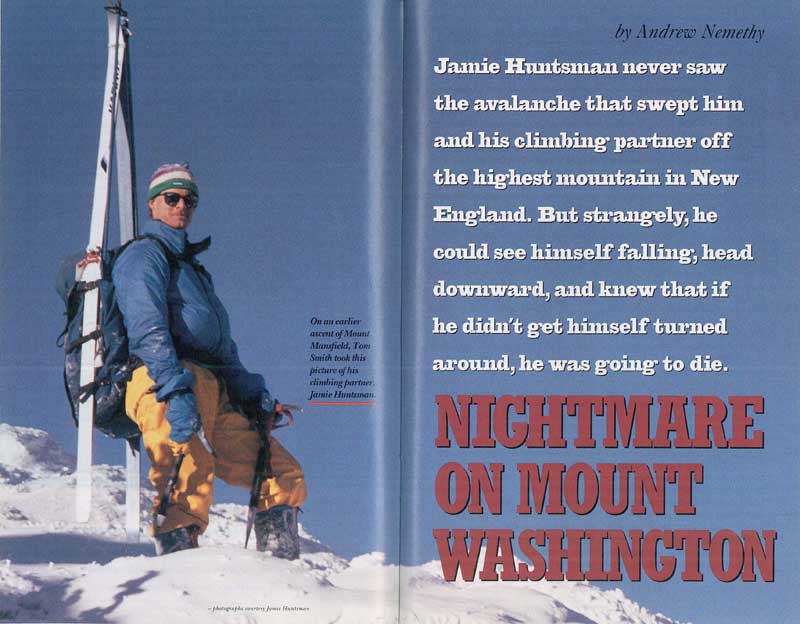

Yankee Magazine March 1993 Jamie Huntsman never saw the avalanche that rumbled down Mount Washington, sweeping him and his climbing partner off the highest mountain in New England. But strangely, he could see himself falling, heading downward, and knew that if he didn’t get himself turned around, he was going to die. The afternoon of […]

Photo Credit : Magazine, Yankee

Yankee Magazine March 1993

Jamie Huntsman never saw the avalanche that rumbled down Mount Washington, sweeping him and his climbing partner off the highest mountain in New England. But strangely, he could see himself falling, heading downward, and knew that if he didn’t get himself turned around, he was going to die.

The afternoon of February 24, 1991, blew in cold and gusty, and Vermonters Tom Smith and Jamie Huntsman felt all of its bluster. By 2:00 P.M. the two avid climbers stood high up in Odell Gully, a steep, icy gash in Huntington Ravine, just a couple of hundred feet below the summit shoulder of 6,288-foot Mount Washington, the Northeast’s tallest peak.

Though nearly at the end of their climb, Jamie, a tall, athletic 36-year-old from Montpelier, was growing anxious. He and Tom, 41, a lean former nationally ranked bicycle racer, had started that morning under starry skies. But the weather had deteriorated all day and now they were wrapped in clouds dense with snow flurries.

Roped together for safety, they had been leapfrogging each other up the gully, cautiously taking turns climbing, then digging in to provide security in case the other slipped or fell — a basic mountaineering technique called belaying. Jamie was leading now, with Tom below providing the belay, and he was encountering loose patches of snow. He thought, “This doesn’t feel good.”

The avalanche danger that morning had been rated low to moderate at the Appalachian Mountain Club Lodge in Pinkham Notch when they started. But Mount Washington is notorious for its changing weather, and Jamie wondered how much snow had fallen in the past few hours.

Jamie carefully worked his way up the narrow, V -shaped sluiceway they had entered after leaving the broad face of ice and rocks in the main gully. He crested a small ice bulge and, once secure on top, dug in a little seat. Sticking his ice ax solidly behind him as an anchor, he roped himself into it and turned to face downhill, setting his crampons in the ice. “Belay on,” he yelled to his partner. “Climb.”

“Climbing,” Tom’s voice echoed up.

Tom, a tall man with an irrepressible sense of humor and remarkable athletic skills, had plunged into ice climbing the last two years with his characteristic enthusiasm. The two had spent the winter practicing on ice all over Vermont, and Tom had twice come to Mount Washington to take ice-climbing lessons. They had been eager to tackle this longer, more challenging climb together.

As Tom worked his way up, Jamie took in the slack line. Suddenly, the world around Jamie went completely white.

“Hold on, snow coming,” he yelled, bracing himself against the startling pressure of a snow slide. Though spooked by the hissing snow, he and Tom had practiced self-arrest techniques and were climbing by the book, so he figured they were OK. When the snow relented, Jamie thought with relief, “We’re holding.”

That was when he heard a roar. Jamie never saw what hit him next. The avalanche blew him off the bulge of ice like a piece of dust, launching him into the air and deep into the heart of a climber’s worst nightmare.

In that instant, Jamie quickly and coolly calculated his options. He was schussing down the gully on his rear, a feet-first human sled out of control. With his ice ax gone, he had only the crampons on his feet to dig in and try to arrest himself He recalled stories of climbers doing that only to snap their ankles, or worse, somersault down the mountain. But as he picked up speed, he knew he had to do something. His best chance was to dig in his crampons when he felt the tug of the rope that tied him to Tom. Even as he thought it, Jamie shot past his climbing partner. Tom was dug in, holding with his toes and ice ax on the steep slope, an indescribable look on his face.

Desperately Jamie slammed his crampons into the ice. They were torn off his feet. No tug of the rope ever came, and with dread and amazement, Jamie realized he was irrevocably plunging to the base of the mountain.

Nearby, atop another route up Odell Gully, Roger Hirt, a 41-year-old auto mechanic from Barre, Vernont, and his climbing partner Jack Pickett, 38, a well-known chef in Stowe, had finished their climb and were waiting to meet up with their friends Jamie and Tom.

Jack and Roger had opted to take a more difficult route than Tom and Jamie, who were soon out of sight to their left. As they climbed, Roger and Jack talked, enjoying the ascent up the ravine, a place Roger felt was “as close to the Alps as you can get.”

But Roger had also grown uneasy about the deteriorating conditions, which cut visibility to one “pitch” of rope — about 150 feet. Roger respected Mount Washington’s dangerous reputation — it had claimed more than 100 lives — and its notorious weather. But by 2:30, the two men reached the summit shoulder. They sat above the gully to eat and await their rendezvous.

After an hour, Roger wondered if their companions had already come up, gone back, and were now sipping hot tea as he and Jack froze at the top. With the whipping snow making it increasingly difficult to see, they decided to descend. They returned via South Gully, one over from Odell.

As they descended, something moved in Jack’s peripheral vision, something falling. His gut feeling was that something was wrong. When they reached the bottom, he and Roger decided not to go down to their car at Pinkham Notch, but back up to the start of Odell Gully in case something was wrong. The two worked their way back around.

From its base, Huntington Ravine rises before the eye in a grand and desolate semicircle of steep rock. Odell Gully is on the left, its narrow entrance marked by the distinctive spire of Pinnacle Buttress and by the long, steep, fan-shaped wedge of hard packed snow that leads to the opening. Hiking up the wooded access trail to Odell, with darkness falling and fatigue setting in, Roger and Jack came to an emergency first aid cache. They hollered up the mountain to see if anyone needed help. They heard someone call back.

During a previous climb that winter, Tom and Jamie had scaled an icy cliff in Vermont and had indulged in some black humor. Tom had joked that a fall would be like playing “human pinball with stone flippers.” He couldn’t have been more prophetic.

The avalanche ripped the two climbers off their perch and poured them down the top chute into the maw of the near-vertical gully. Ricocheting off rocks and ice, Jamie slammed into a huge, scoured, stone slab with his shoulder, bounced off, and then felt himself airborne. “This is taking a long time,” he thought.

He suddenly had the strangest experience of being out of his body. He looked over at himself and saw he was falling head downward. If I want to survive, he thought, I’d better turn myself around. Then he blacked out.

Jamie landed, apparently feet first, on the steep fan of snow at the bottom of Odell, where the slope probably absorbed some impact by sliding him downhill. The rope that tied him to Tom snagged on a treetop sticking out of the snow and prevented the two men from tumbling into the rocks below. In all, they had fallen 1,400 feet, a distance greater than the height of the Empire State Building.

When he came to, Jamie could not believe he was back at the bottom of the climb. Stunned, he took an inventory of his body. His shoulder ached, his rear hurt, he saw blood on his hands and clothes, but he was alive, and no bones seemed to be broken. He heard Tom groaning nearby. He tried to go to him, but intense pain forced him to sit back down. Through the fog of shock, he tried to think what to do. After a moment’s hesitation emergency first aid cache he had never had to call for help before emergency first aid cache Jamie yelled with all his strength.

When Roger and Jack heard the calls, they had no idea who it was. Jack ran toward the gully. Roger ran down nearly a mile to call for help from the radio-phone at Harvard Cabin, an overnight bunkhouse for climbers. Then he headed back up as fast as he could.

Jack gasped for air as he rushed uphill in the direction of the voice. Emerging into the open, he looked up the steep snow slope and saw someone sitting with his head down. The man’s metal-frame pack was shredded like coleslaw, and he looked a mess. As he approached in the fading daylight, Jack was stunned to realize it was Jamie. “Are you OK?” he yelled. “I’m hurt, but I think I’m OK,” Jamie replied.

Jack saw Jamie was in shock and bleeding. He dug a seat in the snow for him so he wouldn’t tumble further and gave him a jacket. Then he located Tom about 25 yards away.

Tom was alive, but had suffered severe internal and head injuries despite wearing a climbing helmet. Jack gingerly moved Tom to make him more comfortable. Then he sat and cradled him waiting for help to come. As he waited, he looked at the mountain in sadness and frustration. He knew he would never look at a mountain in the same way again. “It was the longest hour and a half I ever spent in my life,” Jack later said. “There was nothing I could do.”

As they waited for help, Jamie and Jack called back and forth. Jamie, not knowing that Tom was dying, thanked God for getting the two of them to this point and asked God to help get them down.

When Roger reached the scene, he was drained from exertion. It was so dark he could barely see the three men. He looked in disbelief at a stoic Jamie sitting in the snow and shivering from shock and exposure.

Shortly, the first rangers, Chris Joosen and Ted Dettmar, arrived. They had just finished evacuating another injured climber from Huntington Ravine when Roger’s call came in. They brought two sleeping bags and a thermos of hot Tang. The rangers were concerned not only about the climbers’ injuries, but about the falling snow; their position at the bottom of the gully exposed them all to further avalanches.

An hour later, additional rescuers arrived with a portable sled. Jamie watched their headlamps bob in the steady snow and heard bursts of static and voices on their radios. Jack wrapped his arms around Jamie from behind, trying to keep him still and warm. Through his daze, Jamie overheard a ranger say one of the climbers “was gone,” but he refused to believe Tom had died.

Finally, they strapped Jamie into a sled and lowered him to a waiting U.S. Forest Service Thiokol snow vehicle that took him down the mountain. At 9:20 P.M., more than six hours after his fall, an ambulance rushed Jamie to Androscoggin Valley Hospital in Berlin, New Hampshire. Doctors diagnosed a smashed pubic bone, several deep puncture wounds from his spare ice ax, and bruises so numerous that he looked like a human punching bag. It was clearly a miracle that he had fallen so far and lived. Tom had not been so lucky.

Jamie spent five days in the hospital, kept company by his wife and young son. His body turned the colors of the rainbow, and his mind incessantly turned over the events of that day. Why had his friend become the 106th victim of Mount Washington? Why — and how — had he cheated the mountain? The fall had demolished his backpack, ripped off his watch, mittens, and crampons, and had littered the ravine with his belongings. Two peanut butter, raisin, and honey sandwiches in the pack were reduced to crumbs. “I guess it’s just one of those mysteries that you say, for lack of anything else, is an act of God,” Jamie says.

What happened to the climbers in Huntington Ravine that day may have been a freak convergence of several factors. Though only 2.5 inches of snow were recorded atop the peak on Sunday, the Mount Washington Weather Observatory clocked wind gusts of 139 miles per hour the day before and 74 miles per hour on Sunday. Those winds may have scoured snow off the peak and piled it all above Odell Gully. The added snowfall that day, or perhaps the wind, may have been all it took to trigger the avalanche cascading on the two climbers.

Long after Jamie’s body healed, he continued to feel emotional scars from the accident. Even though rescue crews determined that no one was to blame and the climbers had done everything right, months later Jamie still struggled with feelings of guilt.

In May of 1991, having recovered sufficiently to hike again, Jamie made a somber and solitary pilgrimage back to Huntington Ravine to remember his friend, search for some of their belongings, and try to lay things to rest. In the ravine beneath Odell Gully, he found strewn across the rocks, scattered like the snapshots of two lives, his crampons, his driver’s license, and parts of his wallet. He also found Tom’s goggles and climbing rope. He brought Tom’s gear home and put it away in a box.

“At first, I didn’t do anything with them,” Jamie says. But one day, his young son, Tucker, found the rope and goggles and began playing with them. Jamie realized he felt better having them out of the box, being used.

“It’s something I get to see a lot,” he says. “Every time I see them, I think of him.”