Memory House

As novelist Ann Hood reveals in her essay, we may outgrow where we grew up, but we can never really leave it behind.

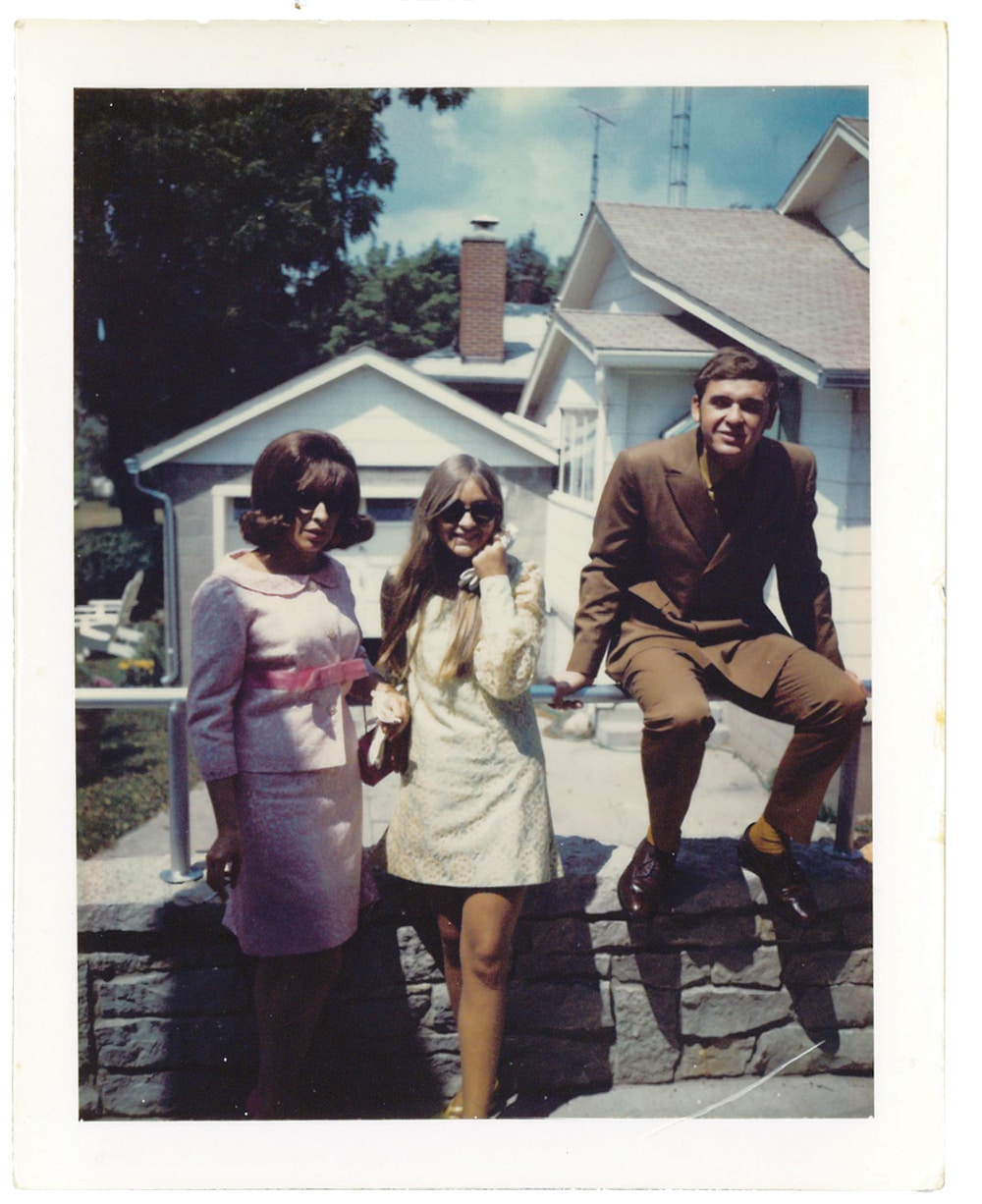

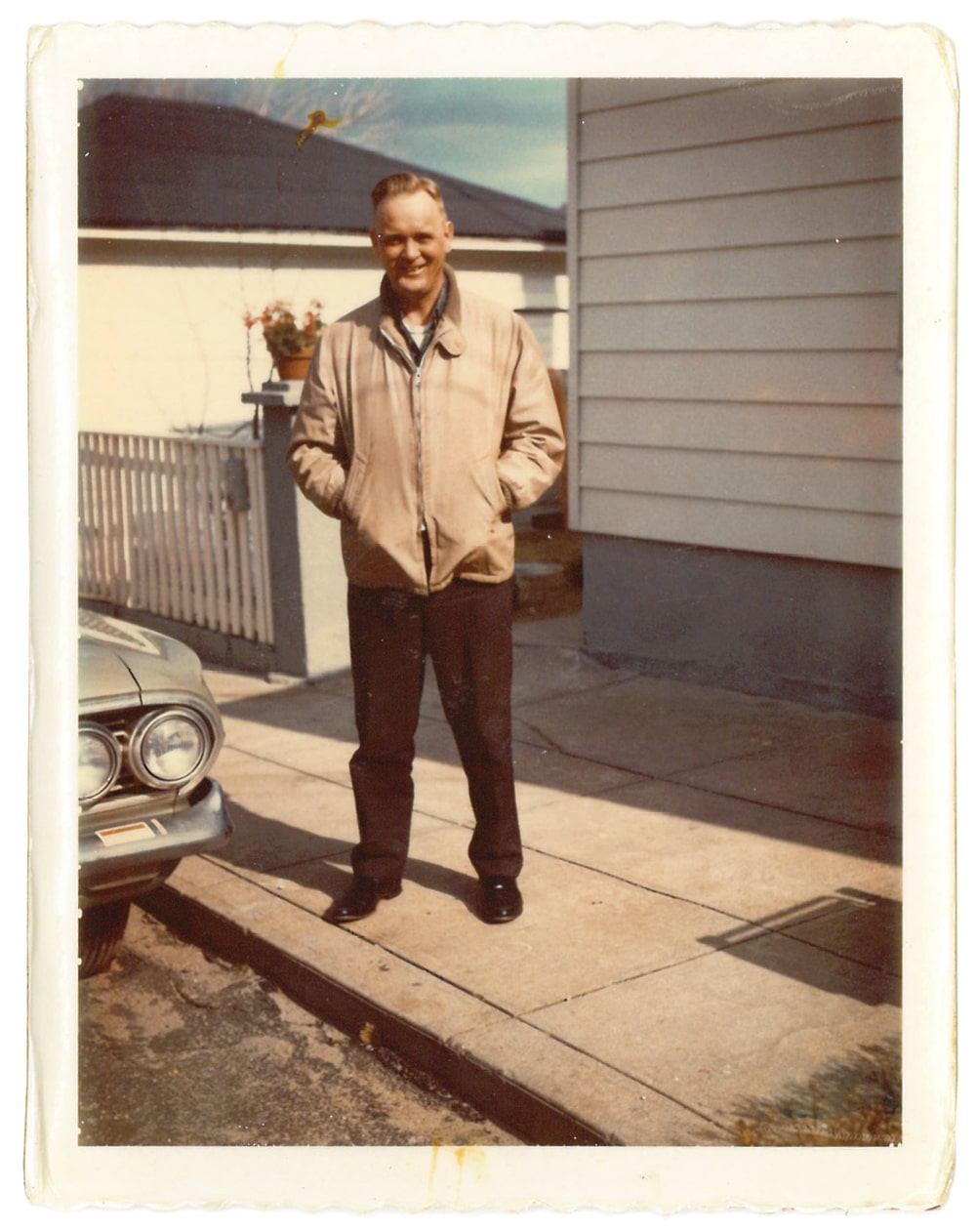

Snapshots from life at 10 Fiume Street.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Ann HoodMost families eventually downsize, buy condos, move to Florida. Mine stays put. We stayed for almost 150 years, ever since my great-grandparents moved from Italy to the house on 10 Fiume Street, in what used to be the Italian section of West Warwick, Rhode Island. The house is not special, except to us. Over the years it changed, and not necessarily for the better. In the beginning, it had leaded pane windows, fancy glass doorknobs, a coal stove and an icebox, and a garden out back filled with fruit trees—apple, cherry, fig—and grapevines and tomato plants that stretched forever.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Ann Hood

In the ’30s, after my grandmother had her 10th child, they built what we called the Shack, a small one-room building nestled by the blueberry bushes, with an enormous stove, a double slate sink, and a table that also seemed to stretch forever. For the next three decades, all meals were eaten there in warm weather. Corn was always being husked at that table, tomatoes and green beans were washed in the sink, a pot of strong coffee bubbled on the stove. When my aunt was widowed, the Shack and most of the garden were leveled to build a new garage with an apartment above it for her and her toddler daughter. Happily, that also was the end of the outhouse, rabbit hutches, and chicken coops, holdovers from the days before plumbing, when we raised everything we ate.

The house got modernized too. Aluminum siding. Wood paneling in every room. A brand-new avocado-green bathroom and harvest-gold glass sliding doors on the china cabinet. Although I, 8 years old and frightened of change (and lightning and dogs and those chickens and, well, almost everything), cried as they cut down the fruit trees and bulldozed the Shack, I quickly fell in love with this new, improved house of ours and all its electric wonders: toothbrushes, carving knife, can opener, stove. In my family, as one generation died, the next just moved upstairs to the biggest bedroom, and it was my mother’s turn. She bought Marimekko sheets with giant red poppies on them and hung a wicker door on one closet, which gave the room a vaguely tropical vibe. Then she settled in for, as it turned out, the next 50 years, at which point it would be my turn to take over that bedroom and the family home.

Except by then, unlike the four generations before me, I had long since left that house and my little town, with no desire to return. And so I sold it, an act that still, a year later, feels like a betrayal. I removed years and years of accumulated papers and knickknacks and just stuff, most of it put into a dumpster and carted away. Even my mother had known that I would sell the house—“Sorry to leave you with such a mess,” she’d say, not really sorry at all. Yet still, as I watched it empty, I felt that I was disappointing all the people who had lived there and died there. We were a family who stayed. But I was the one who didn’t.

———

Months after I sold the house, I stillgo there every night. I walk up the uneven steps of the deck that my father built during a misguided carpentry phase in the late ’70s. The dark red paint has been getting more and more chipped and faded since Dad died over 20 years ago. Every time I stand on that deck, I imagine it filled with people: Dad drinking a cold beer, Mom with a cigarette pressed between her lips, various cousins sitting on each other’s laps because we never had enough chairs. The first time I brought my boyfriend Josh home from New York City, he sat on the railing, which immediately collapsed (thanks to Dad’s poor carpentry skills), sending him tumbling backward a good seven feet. Long after we broke up, the patched railing was still called Josh’s Seat.

When I go inside, I enter what we called the pantry but other people would call the kitchen. In this house, there is always food on the stove. Usually it’s a big pot of spaghetti sauce and the green bowl of meatballs and sausage. Sometimes it’s chicken cutlets, coated with seasoned bread crumbs and fried until crispy. Or pork chops on a sheet pan, sausage and peppers in the red bowl, simmering pasta fagioli.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Ann Hood

“Eat something,” my mother, Gogo, calls from the kitchen, where she is sitting at the table smoking cigarettes, drinking black coffee, and playing poker on her iPad. I fill a plate and pour myself a cup of coffee from the Mr. Coffee machine. My mother makes terrible coffee from a giant can of Maxwell House that sits in the cupboard below the Mr. Coffee. The cups hang from a weird little wire contraption and are always different because my mother changes everything—coffee cups, shower curtain, plates, silverware, rugs, curtains, and knickknacks—to match the season or holiday. These cups, and everything else, are red for Valentine’s Day.

When I walk into the kitchen, she is right where she is supposed to be, sitting at the table in a cloud of cigarette smoke. The table has a red tablecloth with a piece of vinyl over it to protect it. In the center is a tray that holds a pack of Carltons, an ashtray, several colorful lighters, a pen, a letter opener, a deck of Bicycle playing cards, a book of stamps, a wicker basket of red napkins and a smaller one of packets of Equal, and a salt and pepper shaker. It never changes, what’s in that tray. When I was in TWA flight attendant training, we had to be able to identify liquor miniatures just by their shape, without labels. We had to stick our hand into the bar cart and pull out whatever the instructor ordered. I could do that with the tray on my mother’s table. I could close my eyes and locate anything easily.

Gogo is 86 years old, and her cheek, though not wrinkled, feels papery when I kiss it. “Sit down,” she says, her brown eyes shining out at me from behind her glasses. My mother is always happy to see me. Always. “Let’s talk,” she says, finishing her hand of poker. I tell her everything.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Ann Hood

As I talk, I look around. There are the Arts and Crafts chairs with the big, flat cushions by the window. On the wall, the painting of Vermont in autumn that Uncle Jim painted. Beyond this room, the TV room with two La-Z-Boy recliners and a plaid couch. Behind the door is a pillow and a fuzzy mint-green blanket for napping, or for burrowing beneath if you’re sad or sick. The room beside it, the living room, has a straw door now too, and the flowered sofa and armchair are stacked with all the things Gogo used to store in the basement or the garage but, with age, needs to keep close by.

I get us more coffee and we talk about my new husband and my son in Brooklyn and my daughter starting high school. We gossip about cousins and friends and we laugh about things we’ve done or seen and the light coming through the Venetian blinds on the two kitchen windows shifts and it’s time to leave, but I linger, even though I know that tomorrow night, and the next, I will return to walk these rooms, to see my mother again, because the only way to go home is to sleep and dream it, now that it, and she, and everything and everyone is gone.

———

“Home is so sad,” the poet Philip Larkin wrote, “it stays as it was left, shaped to the comfort of the last to go.” The last to go from the house at 10 Fiume Street was my mother. She was born in that house—as were her nine siblings—and she never wanted to leave it. Gogo loved her house. Sometimes when I’d call her and ask what she was doing, she’d say, “I’m just sitting here looking around at my beautiful house.”

It wasn’t beautiful. Not to me. When I was young, I used to imagine us living in a modern house, like the turquoise split-level down the hill. But that was before I learned the difference between a house and a home. I loved all the Little House books back then, and even though Laura Ingalls Wilder wrote, “Home is the nicest word there is,” all I wanted was to leave mine behind.

The last time I saw my mother in her house was on Valentine’s Day, 2017. It had been a strange year. She’d had a heart attack, a psychotic episode from neglecting to take her antidepressants during her recovery from the heart attack, and a litany of small health problems that brought us to the emergency room too often. But she’d announced herself fully recovered from “this so-called heart attack,” and we were going to lunch for Valentine’s Day. We sat at the kitchen table after our steaks at Outback, not knowing it would be the last time the two of us would drink coffee and gossip there. Not knowing that in a few hours she would leave in an ambulance and never return.

The next time I went into the house, two weeks later, she was dead. Everything was as she had left it—her cigarettes and ashtray and online poker game waiting for her. Everything was how it had always been. Over the years, more times than I can recount, this house had taken me in. Weekend breaks from college, unemployment, broken hearts; failed attempts at leaving a bad marriage, even for a night, with my children crowded into my childhood bed with me. It sheltered me, too, in the shock after my brother died at the age of 30, holding the three of us who were left for a long, sad summer. And again during my father’s six months dying of lung cancer, when I would go to the bathroom cabinet and uncap his bottle of Old Spice, just to feel him close. When my 5-year-old daughter, Grace, died a few years later, that kitchen was the only place I felt free to howl with grief. That kitchen, over a century old, knew grief too well by then. The night my favorite aunt died in a car accident, I went home and climbed into bed with my mother, the two of us holding each other beneath the tired roof that had held my family for generations.

Photo Credit : Courtesy of Ann Hood

It was that history that made having to sell the house so difficult. My great-grandmother moved in, and no one ever moved out. Things accumulated in the basement and in closets—so many years of newspapers and photographs and papers that they melded together, forming some new unidentifiable object, an artifact of love. The neighborhood, once all Italians from the same region, distant relatives or friends from the old country, had changed. A few years earlier, after the house was burglarized, the young policeman who took the report said to me, “What do you expect in a neighborhood like this?” I looked around at the familiar street—the hill that I rode my bike down with my hands lifted from the handlebars, the places where we’d play kickball or tag after dinner, the yard where every Fourth of July my father grilled all three meals and then set off fireworks to celebrate not only Independence Day but his birthday too. I could almost hear the John Philip Sousa music he played, almost feel the wind in my hair as I flew down that hill even as I saw what the policeman saw: houses in need of repair, a general shabbiness covering everything. What do you expect in a neighborhood like this?

With my niece and my cousin and my husband, I dismantled over 100 years of our family’s life, most of it put into a dumpster and hauled away. After Merry Maids came and cleaned it, I was supposed to go and inspect their work. But I couldn’t do it. The thought of walking into that kitchen and finding the house empty—of the familiar furniture and knickknacks, yes, but of all the people who belonged there, too—was more than I could take. My husband went, and even though he’d known my family and my home for only a few years, it broke his heart to walk through those empty rooms.

In daylight, I can’t even look at the highway exit that leads to the house. Even as everything changed, keeps changing, in my mind I want 10 Fiume Street to stay exactly the same. I want it to smell like Old Spice and Chloé perfume and cigarettes and meatballs frying. I want my mother at the kitchen table and my father standing at the grill and my brother doing complicated math problems on the sofa. I want that long-haired girl flying endlessly down that hill on her purple bike, lifting her hands from the handlebars, unafraid and untouched by what’s around the corner. Larkin wrote that home is “a joyous shot at how things ought to be.” So I go back every night and walk those rooms, dwelling ever so fleetingly, in that joyous shot of what used to be. Of what, in my heart, still ought to be.