Looking Back on Our Town

Eighty years after Thornton Wilder wrote Our Town, the classic play still lives in the small town of Peterborough, New Hampshire.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine KeenanOur Town is a pretty big deal in our town. The fictional Grover’s Corners in Thornton Wilder’s 1938 play detailing the unexpected power of ordinary small-town life is supposedly based, however loosely, on my own hometown. In Peterborough, New Hampshire, we even like to uppercase the O and T in Our Town’s literature, just to make sure the casual observer knows there’s something more, something else going on beneath the surface. More recently, the street signs at the corner of Main and Grove have been augmented with “at Grover’s Corners.”

Wilder wrote at least part of his Pulitzer Prize winner right here, too, during a stay at the MacDowell Colony, the oldest arts colony in the country, located a couple of miles from downtown. In 2011, when playwright Edward Albee was awarded the MacDowell Medal, given each year to an icon in the arts, he described visiting the colony when he was 23 and bumping into Wilder there. At the time, Albee was trying to be a poet. “My name is Edward Albee, I’m a poet, read these,” he had said to Wilder, thrusting a bundle of poems at him. Wilder read them, took Albee out and got him drunk, and “said a sentence that changed my life,” Albee recalled. Wilder: “Albee, I have read these poems. [Long pause.] Have you ever thought about writing plays?”

Thornton Wilder changed lives. In 1976, I finished my junior year at college, where I was still teetering on the brink of majoring in theater, and arrived home to face a summer of mixing paint at Derby’s Hardware. One day at work, I had just cut a key when the phone rang. The Peterborough Players—our local professional summer theater—was holding auditions for Our Town to replace its lead actress, who’d taken ill. Would I like to try out for the role of Emily? No promises?

I remember being more relaxed at that audition than I’d ever been, for the simple reason that I didn’t think it was the real one. (It was a pre-audition?!) Afterward, I realized it was for real—then I got nervous. I also got the part.

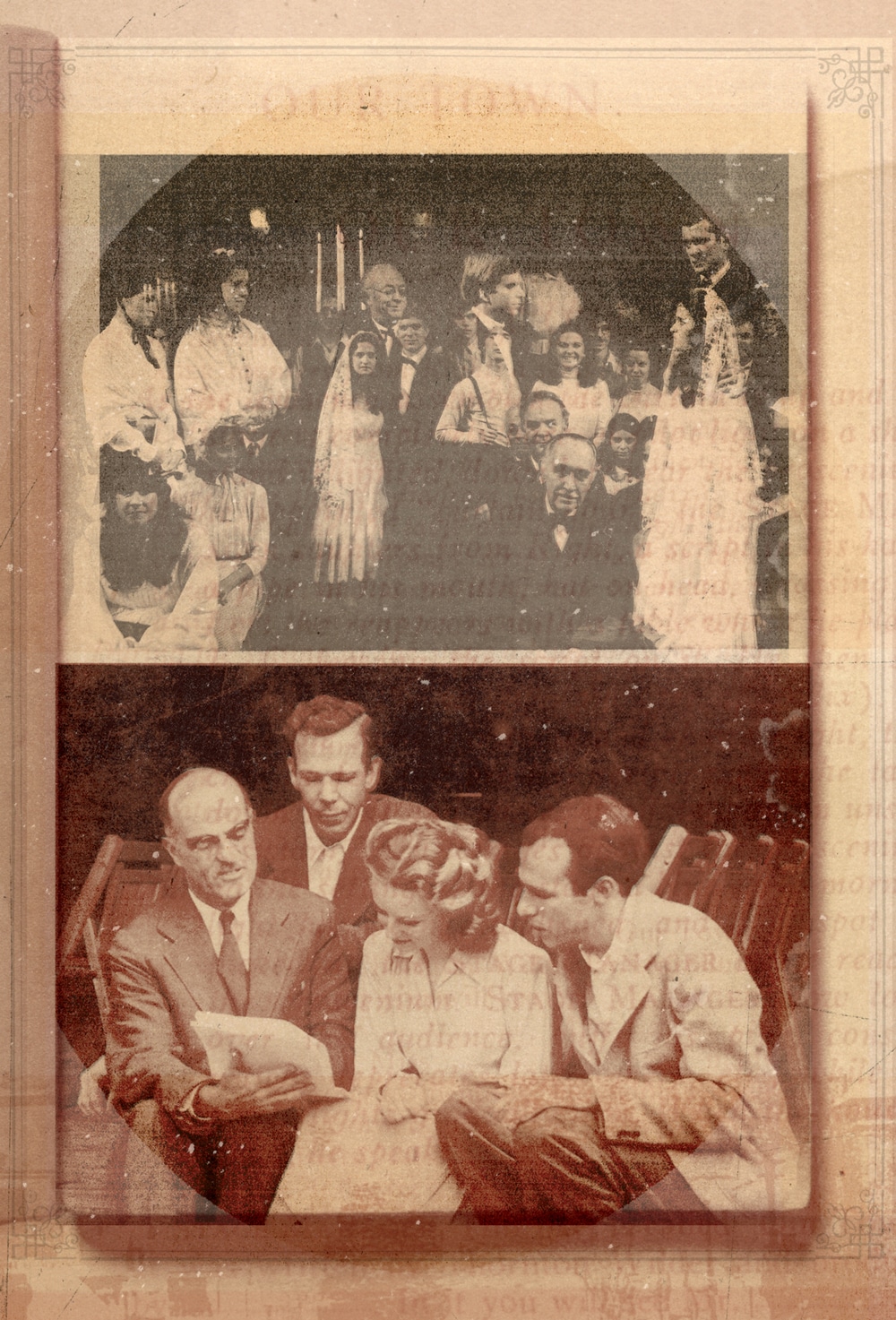

Photo Credit : Peterborough Players (Archival photos)

In the days before “meta,” my casting was supremely so: a small-town girl playing a small-town girl in the small town. On top of that, there was the theatricality of it all. Dialogue to memorize, stage directions and blocking, and daily notes—alongside prickly personalities and backstage romances—all packed into a few weeks of intense rehearsal.

On opening night, I was terrified. We performed in the round, and as my feet hit the slender boardwalk that led to the center of the old barn theater, I left my body, looking down on the scene in a moment that was straight out of Our Town. And then I remembered who I was: Emily. I lived in Grover’s Corners. This was My Town.

Eighty years ago, Our Town made its groundbreaking premiere at the McCarter Theatre in Princeton, New Jersey, on January 22; three days later, it moved to the Wilbur Theatre in Boston. The play used few props, and broke the fourth wall when the character of the Stage Manager spoke directly to the audience (in our production, he addressed my parents on opening night: Good evening, Mr. and Mrs. Graves). In three acts, we met George Gibbs and Emily Webb as children; then as young adults on their wedding day; and finally, nine years later, at Emily’s funeral. And here, Wilder opened us wide. Devastated by her own death and the pain she is causing George, Emily begs the Stage Manager to let her relive just one day.

Choose the least important day in your life. It will be important enough.

I spoke her lines every night. Every night, they broke me in two. We were a hit, adding extra performances and even capturing the attention of a German film crew that was filming a documentary about theater in America. At the time, it felt as though nothing could be more American than this deep, true play that got something so basic so right. Life and death in three acts, in the fictional town of Grover’s Corners, captured with spare beauty by its tender Stage Manager and bright young leads, George and Emily.

Nostalgia can do you in. I know that, more now than I did then, and more still as the years go by. Wilder’s play still winds itself around my heart and brings a lump to my throat, both for the beauty of his words and for their meaning in my life. I remember bits and pieces, on afternoons when I walk down the street where I live to the old, pretty cemetery that “may have been” Wilder’s inspiration. The monuments are a mix of slate, granite, and some kind of pink stone that blooms with lichens, like old-age spots.

People just wild with grief have brought their relatives up to this hill….

It is a graceful landscape, one that I’ve explored for years, and the vista from the high hills behind it is as familiar to me as any city of the living. Here is Tryphena T., flanked by her two husbands. Charlie and Ella, seven months and three months when they slipped away. And their mother, Mary Sophia, just 32 when “drowned by the sinking of the Steamer West Point, August 13, 1862.” Mysteries wrapped in mute heartbreak.

Yes, they stay here while the earth-part of ’em burns away, burns out, and all that time they slowly get indifferent to what’s goin’ on in Grover’s Corners. They’re waitin’. They’re waitin’ for something they feel is comin’. Something important and great. Aren’t they waitin’ for the eternal part in them to come out—clear?

From the back of the cemetery, I look down over the quiet green grass, the rising stones, the river beyond, and the town beyond that. And I hear the lines.

Emily: Do any human beings ever realize life while they live it—every, every minute?

Stage Manager: No—the saints and poets maybe—they do some.

And I want to add: playwrights, too. Sometimes the playwrights help us remember.

What a lovely memory of such an extraordinary impression in your life. Truly the most perfect play ever written.

Annie. enjoyed this. never knew you worked at derby’s. I remember last time i saw the play was at the players and James Whitmore played the narrator. I remember too Paul Newman doing it years ago. take care and thanks again for this.

Thank you for this beautiful reflection. Elizabeth Sobe Cerasuolo

I’ve had the joy of playing the part of the stage manager twice in my life, and this play speaks to the heart of life, each and every time it is performed. someday, i hope to be lucky enough to again be a part of a local production. thank you for this wonderful reminder of how “important and great” this script and play are to our cultural heritage.