Joe Castiglione: The Voice of Red Sox Nation

Since 1983, through good times and not-so-good, Red Sox fans have listened to Joe Castiglione call games on their radios.

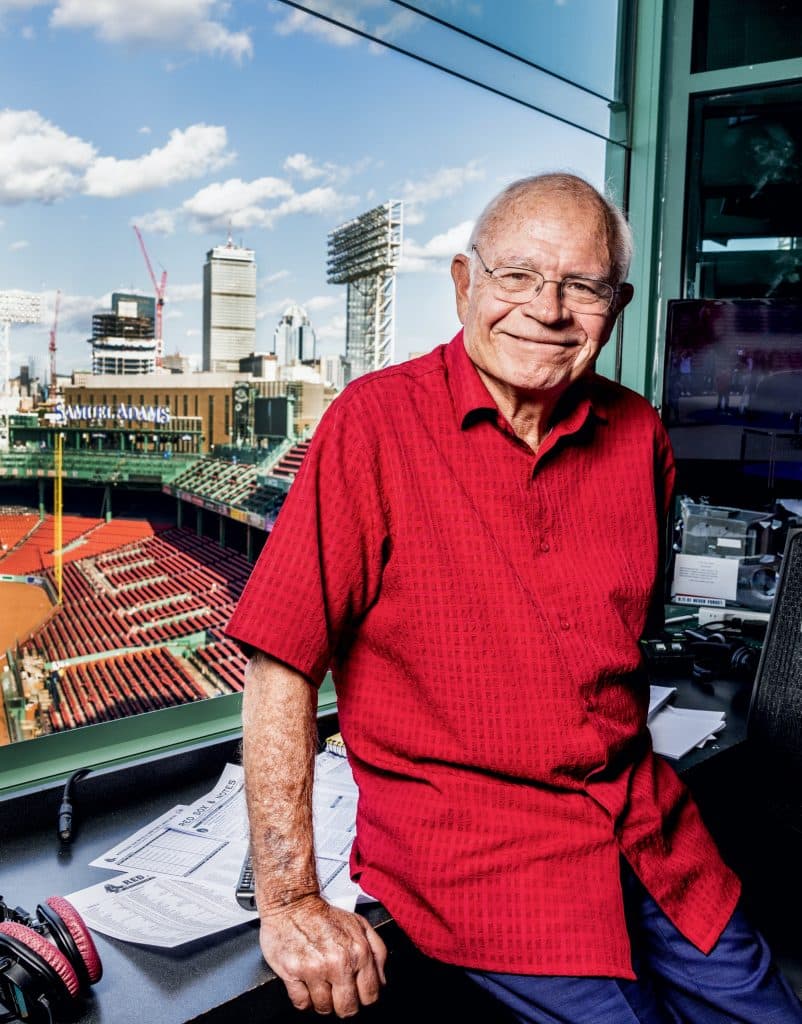

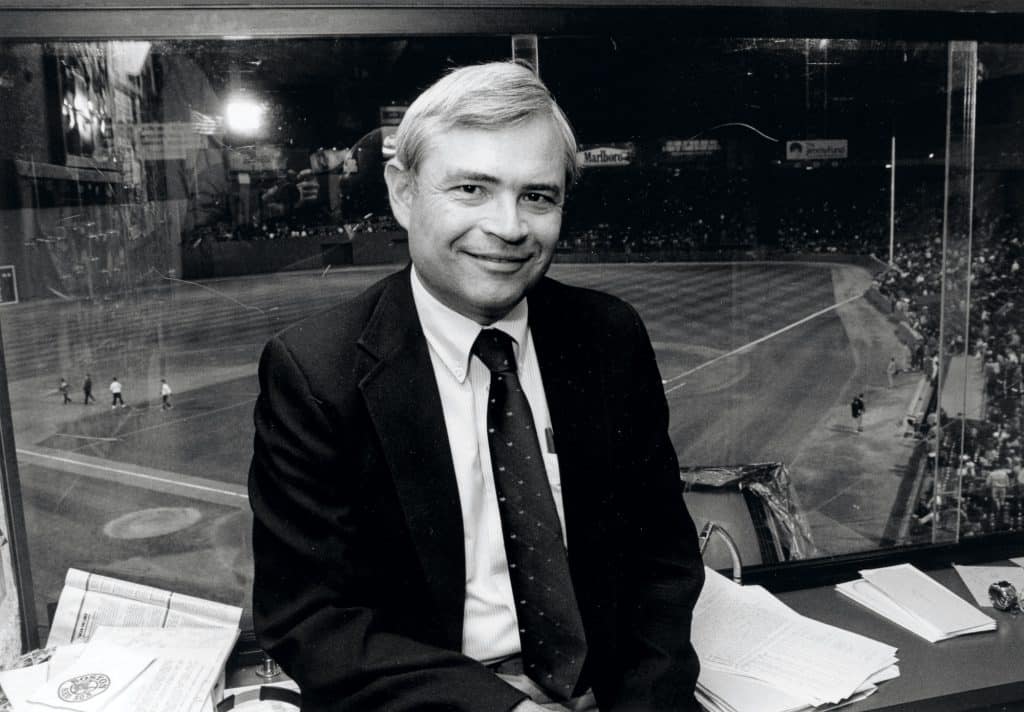

“When you’re broadcasting, you never expect to be anywhere more than three years, let alone 40,” Joe said on NESN last summer, when the Fenway radio booth was officially renamed in his honor.

Photo Credit : Alex GagneI would argue that the home plate at Fenway Park is the spiritual center of New England, the place that resonates with an entire region more clearly than any other single spot. They don’t call it Red Sox Nation for nothing: Big Papi, Yaz, Ted Williams, all the way back to CyYoung. From that 17-inch square, April through (on a good year) October, this place connects us in secular communion 81 nights a year. And if you’re willing to grant that small conceit, then stick with me for one more: If there’s a single voice that unites us, from some invisible line in Connecticut up to the Canadian border, from the shore of Lake Champlain to the beaches of Maine and New Hampshire, from the Greens and the Whites to the Berkshires and the Blue Hills, from the three-deckers of Southie to the potato fields of Aroostook, it’s the calm and gathered one of one Joe Castiglione, for 40 years now the radio voice of the RedSox. “Can you believe it?” he asks when something special happens—and yes we can, because Joe has told us so.

Here’s what it looks like in the radio booth at Fenway (a booth named for Castiglione, with a bronze plaque outside the door). Joe and his broadcast partners—almost always Will Flemming, sometimes Sean McDonough—are cantilevered out over home, staring almost straight down at the catcher and the batter. As the organized chaos of the ballpark proceeds around them (organ music, people proposing on camera, the wave), Joe leans against the wall of the broadcast booth, squinting out at the action below. “Slider away, that’s ball 1.”

His job—most of the time—is to impose a kind of calm on the proceedings, so that those of us listening at home can tune in hour after hour, night after night. It’s the opposite of almost everything else in our media life: not shrill, not loud, not angry, not contentious. Instead, a friend, measured and steady, the sound of spring and summer and autumn as surely as the rising and falling whine of crickets or the play of the surf against the sands of the Cape. His pitch rises when a ball rises, headed for the top of the Green Monster, but most of the time it’s the opposite of drama—because how much tension can you maintain for three hours every night all summer? In a world gone bonkers, he’s the most reliable person in our public life, a representative of some slightly older order. It hurt to lose Mookie Betts; it’s impossible to imagine losing Joe Castig.

Photo Credit : Alex Gagne

The game starts at 7:10 most weekday nights, but the workday starts about three hours earlier, when Joe arrives at the ballpark. He takes the elevator to level 5 and joins longtime producer Doug Lane in the booth, looking down at batting practice, where Joe carefully fills out his scorecard for the night, making notes about the players in a tiny hand. “Some guys use a computer now, but I like it this way,” he says. He’s got high-lighters close to hand, so he can mark homers in green and strikeouts in red. He donated the first 35 years of his scorecards to the New England Sports Museum; the rest are now piling up at home.

Then it’s down to the field, which at least until the gates open to the ticket-holding public at 5:30 is a world populated mostly by “baseball guys”—players, coaches, trainers, reporters, a fraternity that shuffles around the continent from one ballpark to another, dispersing in the off-season to Venezuela or Arizona or some-place else warm enough to keep playing ball, before gathering again for spring training. It’s a fraternity united by, among other things, the history that makes baseball so distinctive, the fact that the game has been played for a century and a half, its records meticulously kept for the obscure as well as the legendary.

Joe begins in the dugout, walking down the wooden steps splintered by the spikes of players, and settling in on the bench to interview Andy Fox, the team’s new “field coordinator.” But not, of course, new to baseball—he’s been a coach in the Red Sox system for a decade, and before that a player with the Yanks, the Marlins, the Expos, the Rangers, and the Diamondbacks, where he set his one real mark of distinction, the team’s single-season record for being hit by pitches. The definition of a journeyman career, in other words, but for Joe—whose baseball memory is almost absurdly encyclopedic—it’s as full of interest as if Fox had been Ty Cobb. He whips out his iPhone, turns on the recorder, and they talk about Fox’s rookie season in New York, where the other newbie was one Derek Jeter, and about the two World Series rings he won, and about the small changes coming to baseball next year (the bases will be three inches larger, but “they call it a game of inches,” as Joe points out), and about the next generation: Fox’s son is a first baseman in high school.

“Does he have some pop in the bat?” Joe asks.

“More than I did,” says Fox.

As if on cue, the next generation of RedSox sluggers wanders into the dugout: Triston Casas, a recent call-up from the minors, who the night before had hit his first Fenway home run, a towering drive that smashed into the DraftKings sign above center field. Casas is a giant, but a friendly one—he nods along as Joe recounts how hard-hitting Blue Jays shortstop Bo Bichette clobbered a ball over the sign that landed on the doorstep of a health club that also happened to be the place where Bichette’s parents had met. Casas points out his own dad, Jose, standing on the dirt by the on-deck circle, so Joe ambles over for a conversation with him and Casas’s grandmother—his abuela—and soon discovers that indeed the son is a student of the game.

“When he was 2 he was watching a game one day, and I could tell that he was watching it, not just seeing it,” Jose says. “He had the mental capacity at 3, 4, 5 to sit and watch, to get inside the players’ heads and figure out why they were doing what they were doing.” On bus trips in the minors, he says, his son would study old World Series games on his computer.

“I love that,” Joe says. “That’s what separates good players from great ones.”

If there’s a mayor of this traveling city that is baseball, it might well be Peter Gammons, the longtime (he went to work in the summer of 1968) Globe sportswriter famous for his weekly compendiums of baseball notes. He’s standing behind the batting cage gathering fodder for his next column, so I walk over to ask about Joe.

“He’s one of the most joyous people I’ve ever encountered,” Gammons says. “And he has to be, when he’s working every single game. He’s the ultimate professional—you can tell because when he does those commercials for Shaw’s supermarket and he’s talking about fruit, he does it well. He doesn’t grouse about having to talk about vegetables, because it’s part of the job. He’s a pure baseball guy.”

That “pure baseball guy” thing is almost comically accurate. We head back up to the booth, and through its side window we can see the Yankees broadcast team doing their prep work. “That’s David Cone,” says Joe, waving through the window. “His ex-mother-in-law was my high school biology teacher. She was very tough.” (Castiglione grew up in Hamden, Connecticut, near enough to the Big Apple that he was a fan of the Bronx Bombers as a boy.) Next to Cone is his broadcast partner, John Flaherty. “He caught for several teams, including the Sox,” says Joe. “We traded him. Big mistake. He came back and broke up Pedro Martinez’s no-hitter in 2000. He’s a great guy, his daughter is at Northeastern.” And so on.

Photo Credit : Boston Red Sox

An hour before the first pitch, we wander into the small dining room that the Red Sox run for reporters, just feet behind the radio booth, and take over a small table. Over lobster mac and cheese, Joe talks about his favorite ballparks (“Yankee Stadium is always special, even the new one; Baltimore’s great; Seattle is a beautiful park”), and about learning to call games as an undergraduate at Colgate, and the time die-hard Sox fan Stephen King put him in a book (The Girl WhoLoved Tom Gordon), and how at this point he can tell without even looking at the clock that it’s closing in on 7 and the national anthem.

Before it gets too close to game time, I move a few seats over to talk to Flemming, who was the broadcaster for the Sox Triple-A affiliate in Pawtucket (now Worcester) before getting the call-up to the bigs in 2019. “Joe doesn’t just know everyone at the ballpark,” he says. “He knows everyone at the hotel, everyone in the coffee shop, he knows the guy who rents the kayaks. And he shows it all to me. The baseball lifestyle is rough—I’ve got two young kids and a wife, so being on the road is…. But to have a true friend out there with you, it goes a long way towards making that road lifestyle an enriching experience.”

In the past few weeks, as the Sox wandered the country, Joe had taken him to the Negro League Hall of Fame in Kansas City, the Roberto Clemente Museum in Pittsburgh, and the Babe Ruth Museum in Baltimore—indeed, they’d gone on to the site of St. Mary’s Industrial School, where Ruth had spent his adolescence playing ball. “Joe seeks out new information even after 40 years. Every day is exciting and new to him; he’s always reading, researching, talking,” Flemming says. “So every night I take it as my job to, two or three times, lead him into some episode in Red Sox history, whether it’s about the most famous or the most obscure, and then to get out of the way. For great Red Sox fans listening to our podcast, that stuff is ambrosia.”

Flemming does college basketball broadcasts on TV in the winter. “It couldn’t be more different. You’re just captioning the pictures,” he says. “In the Red Sox games, storytelling is the point. Joe brings an amazing warmth. In a divided world, you can really feel it.”

The baseball world is divided, too, of course, as anyone who’s ever listened to Fenway heartily chanting “Yankees suck!” can attest. But truth be told, there’s very little tension tonight as the Red Sox take the field behind rookie right-hander Brayan Bello. It’s been a mediocre season for the Boston nine, who have been plagued by injury, and now halfway into September they’re hovering below .500, any hope of making the playoffs long since abandoned. But at five past the hour, as the commercial for Safelite AutoGlass ends, Joe is at the mic.

“Good evening, everyone, and welcome to Fenway Park, for the final Fenway appearance this year of the Yanks. All eyes will be on Aaron Judge tonight, with the Yankee slugger sitting on 57 home runs with 19 more games to go to break Roger Maris’s single-season Yankee record.”

But Judge, up first in the lineup, grounds out while the crowd is still filing in, and it sets the tone for the evening—a really bad ballgame. The Red Sox make errors on the basepaths and on the field (the center fielder, a recently arrived fill-in at the end of his career, manages to drop two balls in a row), and the heart of their lineup (Xander Bogaerts, Rafael Devers, J.D. Martinez) strikes out again and again, Bogaerts dropping out of the top of the American League batting race. Still, it’s a lovely late-summer evening, and the scene at the park goes happily on—a woman tearfully accepts a wedding proposal on the jumbotron, and in the booth they find something to talk about. Bello, the rookie pitcher, looks sharp in spots; he’s begun his career with 39 innings where he hasn’t given up a homer, the best for the Red Sox since one Luis Aponte, another Red Sox right-hander who compiled a 9-6 career record back in the ’70s and ’80s. “I’ll never forget a homer he hit to win a game,” says Joe, who apparently never forgets anything.

Over the three-plus hours that the game stretches on, Joe finds time to riff on Judge’s chances to win Most Valuable Player (almost a lock, especially since his team will win the division, though “of course Ernie Banks won two straight MVPs for a Cubs team that was one of baseball’s worst”), and to remind us that Shaw’s is selling 80 percent lean ground beef for $2.77 a pound, and that former Brooklyn Dodgers GM Branch Rickey was known as El Cheapo to his players, and that the attendance tonight is 36,581, and that Houston is the team to beat for the World Series this year. At one point, on his way to the men’s room in between innings, he looks up at me and says,“ In a season like this, all you can do is look for individual performances, and hope for good games. And this is not a good game.”

But it is a game, and Joe’s a professional to the final pitch. A professional, and also an amateur—still intrigued by the possibilities of this most complex of games. I try to do some statistical calculating of my own: 40 years times 162 games times three hours, plus spring training and some deep playoff runs, equals something like 19,440 hours of broadcasting. At an average 292 pitches a game, that’s closing in on 2 million times that he’s watched a slider or a hook or a heater come to the plate, and somehow his enthusiasm has not wavered. He’s not cynical or bored or resentful of the millionaires making errors on the field below; he’s clearly happy to be sitting precisely where he sits, at the center of an entire region. Now he’s telling the fans about his talk before the game with Triston Casas’s doting father. “He says his son is a real student of baseball history,” says Joe. “That will take him a long way.”

This feature first appeared in the March/April 2023 issue of Yankee Magazine