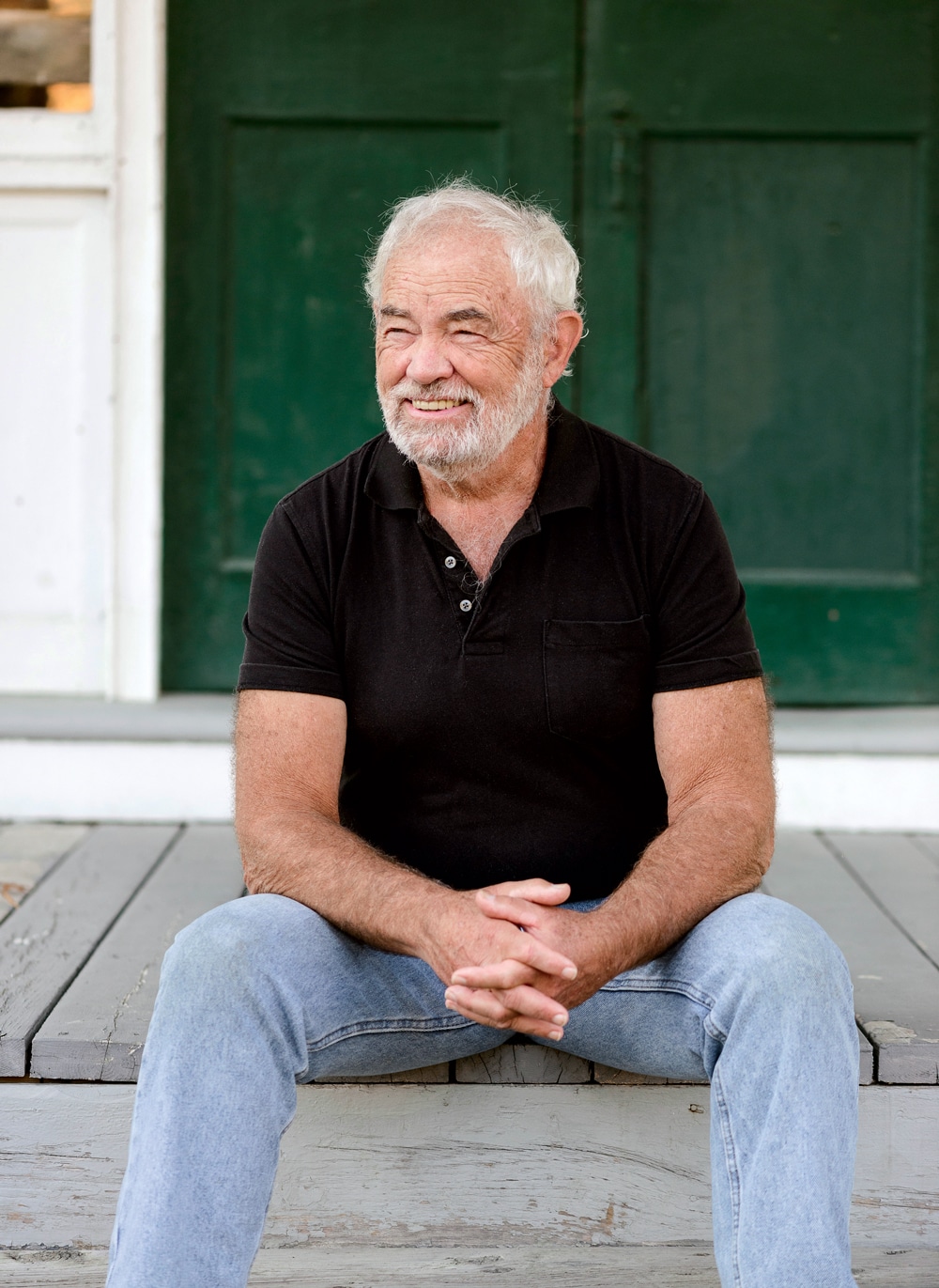

Is Small Still Beautiful? | The Big Question with Frank Bryan

Is small still beautiful? We ask Frank Bryan, a prolific author, beloved UVM professor emeritus, and ardent Vermonter.

Coffee By Design | Portland, Maine

Photo Credit : Katherine Keenan I graduated from high school in 1959, in Newbury, Vermont. There were seven of us. I graduated in the top three, at about a 72 average—the highest of the five boys. We had a lot of people think, Oh my God, it’s a small town, it’s way the hell gone, which is true. Yet we did get radio and television. I remember listening to country music from WVA in Wheeling, West Virginia—but it had to be nighttime.”

I graduated from high school in 1959, in Newbury, Vermont. There were seven of us. I graduated in the top three, at about a 72 average—the highest of the five boys. We had a lot of people think, Oh my God, it’s a small town, it’s way the hell gone, which is true. Yet we did get radio and television. I remember listening to country music from WVA in Wheeling, West Virginia—but it had to be nighttime.”

—

“I got in trouble a few times, but I was protected by the community. If you did something bad, everyone knew your circumstances, so they could cut you some slack—or not. That has the benefits of ‘small’ but also its biases. But yeah, it worked out pretty well for me.”

—

“Most of my professional work has been involved with the relationship between size and policy, size and politics.”

—

“I was rejected as an undergrad at the University of Vermont, where later I got tenure and even held the political science department’s only honorary chair at the time. I never let them forget they’d rejected me as an undergrad.”

—

“New England is different from any other place. It’s got everything. It’s got mountains. It’s got a seacoast. It’s got ‘smalls.’ It’s got ‘bigs.’ A couple of professional sports teams. I remember my grammy holding me on her knee when Ted Williams was coming to bat back in those old days. She said, ‘Don’t worry, my Teddy will take care of it.’ So it wasn’t as parochial as you might think.”

—

“You know, ideological connotations are so different now. To be a conservative used to mean you were for ‘small is beautiful’ or states’ rights—which was dangerous, because the South was still institutionally racist. But in Vermont it also meant being for town meeting, town control, and local politics. So I was always on the outs in Vermont, because that wasn’t a time when town meeting was appreciated much, and everyone thought it was old, silly, archaic ‘little town’ stuff. But it affected me a lot.”

—

“Without my students I couldn’t have written my book (Real Democracy: The New England Town Meeting and How It Works). Every year I sent 40 to 100 students to town meetings all over Vermont. They had to count the number of people who were there: how many women, how many men. They wrote down who spoke, if they spoke again. That kind of research had never been done before. The students loved it. Two-thirds were from out of state, and when I sent them from Burlington to way-up-there Vermont, they’d come back with stories. They really got a kick out of it. And they learned that pure democracy isn’t as pure as the word, and it’s real.”

—

“People call me a romantic on town meeting, but if you read my stuff there’s nothing romantic about it. I would say spending a couple of hours a year at town meeting shows more commitment than voting. Voting is so easy. You go into a booth; nobody can see what you’re doing. But get up in front of 75 to 100 people, and everybody can see you. They can see your face. I think it’s a great socialization of democracy.”

—

“There is absolutely no doubt that civil rights and civil liberties cannot be local. Anywhere. Your rights as an American are the same anywhere you are. Environmental protection can’t be local. The Connecticut River is a great example there: The river is owned by New Hampshire, but really it should be controlled by New England, at least, so that’s a bad boundary. Some things cannot be administered at the local level and should not be. And the key is figuring that out. Unwrapping it.”

—

“I’m no longer a secessionist, because I feel sorry for America. I think America is in real trouble. Whereas in the past I had no moral hesitation at all, now I think it would be a cheap shot at a hard time.”

Does anyone have an email for professor Bryan, I was a student of his and I wanted to reach out. Thanks